by

Ken Magri

Warhol never preached any specific art dogma, and the commentary in his works was usually vague; open to some interpretation. The images, however did manage to mirror a cold war era America infatuated with itself, while celebrating the brand name abundance which characterized most of the country and most of Pop art in the 60s. Silkscreened soup cans, Coke bottles, car crashes and movie stars took on a more iconic meaning under his repetitive eye.

Cal State Sacramento professor Kurt von Meier likened Andy's thinking to that of the Dadaist Marcel Duchamp and his ideas about the function of choice, which were brilliantly revived in Warhol's art. "Of all the images of Marilyn Monroe, he chose the one that went straight to the archetype," said von Meier. "Through his choice he was able to focus on the essence."

Warhol dumbfounded most art critics by striking at the so-called mystique of art and returning it to a pedestrian aesthetic. Images of race riots, Jackie Kennedy, electric chairs and Chairman Mao, gleaned straight from the front pages of newspapers, were familiar to the average American, even though Warhol put his own spin on them. While speaking of the superficiality in our lives, his flat colored, hastily rendered canvases seemed to celebrate it just the same.

"I sensed anger in some of his work," said Sacramento artist Darrell Forney. "There was a certain edge that kept it alive." Forney saw Warhol as an iconoclast, especially in his tradition-breaking use of film. "I was a graduate student at California College of Arts and Crafts in 1963, when all the Pop artist were making their impact. I would hit the Bay Area film festivals and inevitably see a Warhol film."

In many ways the artist's films posed a greater challenge than his art by setting extreme precedents for their unrelenting sexual themes and/or duration. Consider two examples from 1964, each shot with a static camera from a fixed viewpoint. "Empire" was eight hours of the top half of the Empire State building, and "Blow Job" focused on a young man's face while an off camera participant performed fellatio on him.

People often dismissed Andy's films as camp put-ons and amateurish exercises in non-technique. Still others found significance in his willingness to push the boundaries of cinema beyond mere Hollywood standards. As the years progressed Warhol used more traditional techniques, but continued to explore explicit sexual themes that would generate protests or police confiscations.

|

|

Without Andy's continual attack on artistic taboos, later films like John Schlesinger's "Midnight Cowboy" and Bernardo Bertalucci's "Last Tango in Paris" would never have achieved Academy Award consideration. Warhol broke the ice, although film soon became a temporary means of expression.

Warhol slowed down considerably after surviving a near fatal point-blank shooting in 1968 at the hands of a disturbed young woman who wanted him to produce a film script she wrote. It seems so distant now to remember what a horribly violent year that was. The Soviets rolled their tanks into Prague, the Tet Offensive began in Viet Nam, Martin Luther King was assassinated, and while Warhol recovered from surgery to save his life, the news came in about Robert Kennedy's assassination. Out of the chaos and tragedy that enveloped the world that year Warhol became just another victim. He was never the same after 1968, but neither was America.

Throughout most of the 70s and 80s a mellowed Warhol concentrated on celebrity portraits and his new "Interview" magazine, a visually hip foray into the chic, if not substantive, side of New York glitterati. He was always seen with superstars (a word he coined, by the way), many of whom became his subjects.

|

|

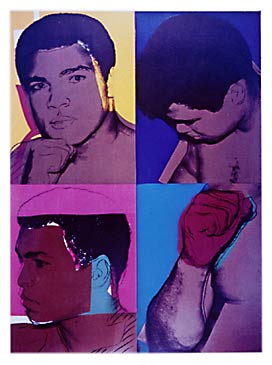

The list of notables included Mick Jagger, Muhammad Ali, Aretha Franklin, Jane Fonda, O.J. Simpson, Jimmy Carter, Liza Minnelli and fellow artist R.C. Gorman.

As a celebrity himself, Warhol endorsed everything from ice cream to office furniture. As a collector he purchased fabulous examples of contemporary paintings, Federalist period furniture, Art Deco housewares and Navajo rugs. He penned two books, did cameos in "Tootsie," on "Saturday Night Live" and "The Love Boat," and, at some point, became famous for being famous. While still making art right up to end in 1987, Warhol's final masterpiece was the successful marketing of himself as the most recognizable artist since Pablo Picasso.

Often portrayed as an enfant terrible, his most endearing characteristic, ironically, was his frailty. "He was shy, with almost a boyish quality," said Lisa Stanley, who helped arrange his 1981 appearance at the Weinstock's in downtown Sacramento. I met him that night and would agree. Warhol acted at times as if he was as surprised by his fame as anyone else.

Some art critics like Robert Hughes tried to downplay Warhol's importance, saying "his ideas had a half life," and that in the end he was little more than a "perfunctory social portraitist." But Hughes changed his tune in the 1990s, once it was apparent that Andy had inspired a whole wave of younger New York artists like Keith haring, Ronnie Cutone, Kenny Scharf, and especially Jean Michel Basquait whom Warhol befriended and collaborated with.

"Look," said von Meier, "New York society can be voracious, yet it never gobbled him up." In the end it will be said that Andy Warhol far outlasted the 15 minutes of fame he accurately predicted for everybody else. "My gut hunch is that he is going to survive very well," said Forney.