ABSTRACT

Public participants in

the “saving of the planet” have long been the rallying cry of the organizations

soliciting funds for the continued development of conservation programs. Other

than cash donations, no program has elicited the actually participation of the

common citizen in the process of identification and tracking of individual

sightings of endangered species. This

paper proposes that this type of database can exist and proposes a platform for

accomplishment.

INTRODUCTION

In an age of decreasing Federal and State budgets the public

at large has become an ever increasing vehicle for augmentation of

scientific information gathering and study.

Private companies and educational institutions are

supplementing governmental efforts to develop and populate

biologic databases, gather and store physical data, and facilitate

communications between public and governmental agencies.

“All 50 states and the District of Columbia have some listed endangered

species. Hawaii and California lead

other states in numbers of endangered species designations: Hawaii with 308 and

California with 259. Since 1973, 29

species have been “delisted” or removed from the endangered species list, seven

of those due to extinction.” (1) (This is appalling!)

With the exponential increase in the use of the World Wide

Web information is easier to access and obtain.

Many amateur scientists can now explore the

world around them without the discomfort or inconvenience of

leaving their homes. For those

with a greater sense of curiosity the Internet serves as a

"jumping-off" spot for further exploration. Initial ideas can be explored,

researched, and refined so that individuals can explore

individual tastes and desires to the level of their individual liking.

As opposed to the general thinking of the government, the

public should be welcomed into the research and data gathering process. By utilizing interested and trained citizens

budgets can be managed and valuable data reported and entered into databases

for scientific study. Minimal training

would be necessary to incorporate lay people into the information-gathering

database. All training projects could

be accessible online. Guidelines,

forms, and contact information can all be made available on the Internet. Information management can then be

maintained by professionals at either a clearinghouse or at specific

departments targeted depending on the information obtained.

Utilizing budget monies for populating databases with

information gathered from the public is a more efficient use of funds. Information can then be forwarded to

governmental departments such as the Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and

Wildlife Service, Marine Fisheries Service, and various Ecological services

throughout the United States and made available for worldwide use. Information can be placed into predetermined

format on an interactive website.

Citizens can enter observations and data transferred from Field

Collection Forms. There can be an area

for transferring scanned graphic images such as photographs to augment

observations. Having this information

available to all interested scientists and lay people in a read only format

allows this data to be copied to project databases and utilized in populating

data fields for informational and decision-making situations.

Utilizing the California Natural Diversity Database as an

example of a database that could be augmented by private citizen observations I

will prove that lay scientists can provide an invaluable “set of eyes” to

further explore the natural environment with minimal additional burden to the

supervising department. This burden

comes in the forms of processing personnel to take the observational data and

format it into useable data within an interim database. Once verification can be done, the data can

then be added to the database as an additional source of location information

for use by various professionals.

Data added to the database can be notated so that persons

using the database will be able to know which data had been generated by the

issuing agency and which data had been provided by outside sources. When professional or lay scientists need to

research a particular plant they can then use both forms of data corroborating

independently gathered data or discounting it, depending upon the direction of

their study.

METHODS

Taking into consideration the above-mentioned database concerns, I proceeded with

research and development of a plan whereby any citizen could act upon desires to help

the environment by adding to the scientific knowledge stored

about a plant species. This information

could be found either upon concentrated effort of a hiking mission to find the

plant, or by accident while on a hike by a prepared trekker.

I began my research by evaluating different sources of

possible links to databases already in existence.

I examined the previous two years issues of GeoTimes,

Geo World, and National Parks magazines.

Unfortunately these proved to be virtually

fruitless. I was unable to find even

the hint of a reference to any project either closely resembling what I was

seeking or a mention of the type of data gathering that I was proposing.

I then proceeded to the World Wide Web.

The Internet proved to be of limited use when researching

data and links that specifically dealt with Natural Resource and Endangered

Species databases in the public sector.

Most of the references that I found were through specific university

projects and most had little to do with Endangered Species at all.

I made the attempt to contact all projects

that seemed remotely in the discipline I was trying to find.

After attempting contact with over 50

various projects and databases; there were no responses to the majority of

e-inquiries sent. In most cases there

was no telephone number for contact and tries to the varied universities

brought no return phone calls. Many of

the databases had not been updated for a period of several years and the

contacts were no longer valid and returned only undeliverable e-mail responses.

There was one exception to the above. The Manzanita Project being administered by

the California Academy of Sciences Library.

Though this project does not specifically deal with Endangered Species

either in the plant or animal variety; it did provide a link to further

development of my idea.

I also contacted the Western Ecological Research Center just

outside the gates of Yosemite National Park.

Jan van Wagtendonk, (PhD) was very helpful and illuminating in his

explanations of the research work going at his facility in the realm of

Endangered and Rare plants within the regions of Mariposa and Tuolumne

counties. When I went to the facility

to speak with Dr. van Wagtendonk he showed me the information gathering equipment,

processing equipment, and analytical data resources used. Currently his primary

assignment is in the area of predictive modeling for fire prevention and

prediction services.

His facility also tracks much of the biodiversity within the

region. He has large volumes of maps

and photographs of plants within the territory that the W.E.R.C. is responsive

to. With the use of sophisticated

Geographic Information Services equipment in the field currently including the

use of a digital camera, and computer processing of images and data available

back at the project headquarters, the Western Ecological Research Center has

built a large library of images and geo-referenced locations for may of the

areas endangered and rare species.

Though many of these resources are not available to the general public,

Dr. vanWagtendonk is very forth coming with information from their studies and

possible areas to examine for specific plant species.

RESULTS

In contacting the California Academy of Sciences, I was

fortunate to receive a response from Carrie Burroughs, staff member of the

Manzanita Project. She informed me; “We

do not have any plans to incorporate other data into our system at this point

in time. It seems slow enough, as it

is, just getting the basic data cataloged for each image.” (Burroughs, 2000).

The images that Ms. Burroughs is referring to are displayed

on the Manzantia Project web site: http://www.calacademy.org/research/library/manzanita/html/.

She went on by saying; “Generally speaking,

photographers that want to contribute to the project donate slides to our

collection so that we then control copyright on those images.” (Burroughs,

2000) The images on the Manzanita Project

website are general photographs of California flora, with an emphasis on

Endangered plants. They invite

photographers to contribute to this “first phase” of the database and provide

basic information of photograph gathering and a list of some 100 species

identified by the State of California and rare or endangered.

On the Project Description page of the website; http://www.calacademy.org/research/library/manzanita/html/discript.htm

the first project goal is described as;

“An initial goal is to create a computer database containing images of

rare, threatened, and endangered plants and animals of California.” (3) The Academy is trying to create a

biodiversity catalog of California’s wildlife for educators, students, and all

interested parties to access. There is

also a list of the Federal listed endangered and rare plants for

examination.

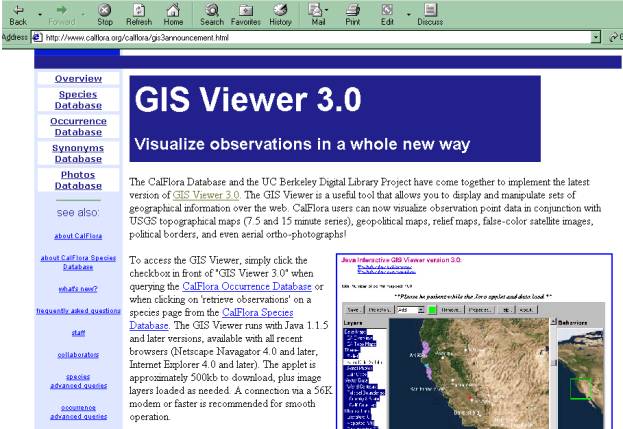

Ms. Burroughs also directed me to CalFlora. This website has pictures of many of the

state’s rarest plant species. The

CalFlora site also has instituted a GIS Viewer 3.0 page to help “Visualize observations in a whole new way.” This

website is co-sponsored by the CalFlora database and the UC Berkeley Digital Library Project. They mention that the

GIS Viewer is a useful tool that will display and manipulate sets of

geographical information over the web.

I have included the web page capture below to help you to understand the

layout of the site:

This information makes it possible for enthusiasts to

research their trek before heading out and to better visualize the terrain that they will be accessing when they go in search of the Endangered and Rare plants. These plants are not readily observable and must be carefully tracked in order to insure accurate reporting

of sightings.

Point positions can be gathered and then later researched on

the CalFlora GIS Viewer. This would allow any one with a GPS unit to be able to

provide an accurate position for their find while out hiking.

With the accompanying photograph, this

information could be utilized to provide an invaluable resource for accurate

information gathering.

In Geo World there was one reference to this ability to

utilize field data in the field: “Moreover, the development of palm-sized units

promises an explosion of light, fast and inexpensive data collection tools in

the years ahead" (Jonas, Mark, Hillman, Barry 2000).

The advent of smaller data gathering tools; hand-held GPS units,

Digital cameras, and laptop computers will allow far more accurate information from even the most novice scientist.

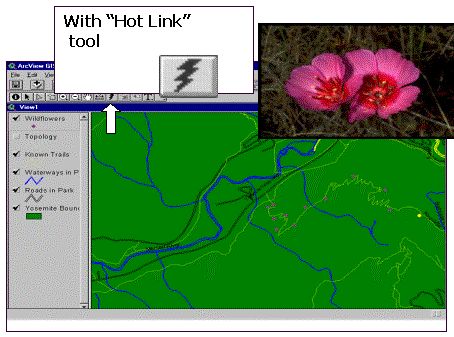

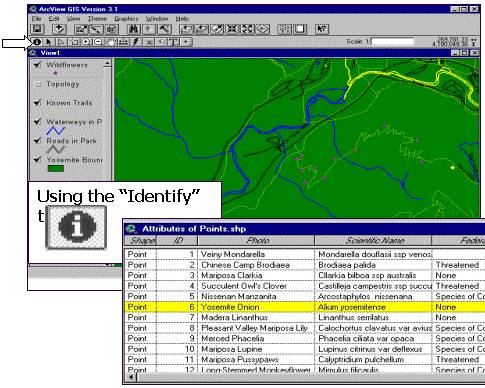

Information can then be displayed using a tool such as ArcView in the

following manner:

By using the tools built into the Arc View program the data gathered could be displayed with either the picture data “Hot Linked” to the theme map as in the above example or by accessing the attribute data by using the “Identify” button as in the example below.

ANALYSIS

Many avenues of exploration were used in the culmination of this project.

Many of them encountered dead-ends. The answers gathered from the

Manzanita Project allowed me to think that the possibility of augmented an

existing database might prove to be a good initial step in the realization of a

publicly augmented natural resource database.

By utilizing the Manzanita Project’s guidelines for picture submission, amateur

photographers and scientists will be able to understand the format needed for

their research to be validated into a research database.

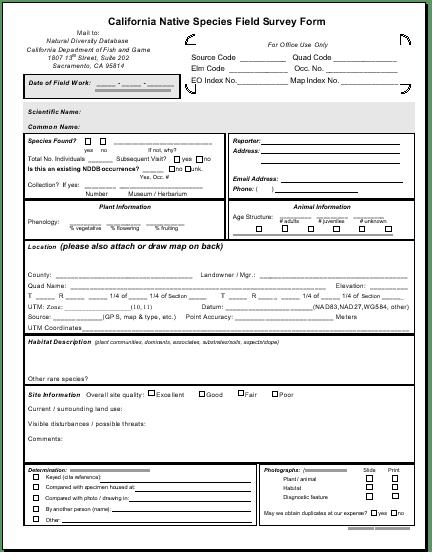

Using a Field Survey Form provided by the CNDDB (California Natural

Diversity Data Base), these same people will be able to understand the nature

and depth of the accompanying data to these photographs. The forms (shown

below) would help in the assurance that correct information was gathered at the

time of encounter, and that the information is as complete as possible. The

example I have used is the Native Species Field Survey form found on the

CNDDB website (4).

By adding these two components together any citizen would have the ability to collect valid, verifiable information that could be examined and used to augment any natural diversity database.

CONCLUSION

Given the difficulties that I encountered with this proposal, easy conclusions did not present themselves. Though enthusiasm for the project has not waned; the size of the task needs to be re-evaluated.

- Coordination of a database populated wholly or in part by non-scientists will need funding – possibly through the grant process.

- Initial building of the database would require substantial effort by grant holders.

- Ongoing support for the database will require repeating the granting process or obtaining sponsorship from a foundation.

The possibility for augmentation into an existing database also exists. This would also require a grant for the initial phases to be able to facilitate meeting with potential candidates to discuss feasibility. Once a partner has been determined, efforts would need to be concentrated in setting up goals for introduction, maintenance and personnel issues for data processing.

After the design and initial implementation phase of the project is completed; the idea could then be revisited and the continued successes evaluated. There would then be quantifiable results tables that would allow decision making on the quantity of the information presented for processing, the accuracy of that information, and the amount of independent corroboration that would be necessary to validate new sightings and instances of plant identification. The

project could also be evaluated for man-hours needed for processing

information based on the responses received during the evaluation period.

All in all this project has the earmarks of allowing citizens to participate in the

recovery of the planet by participating in the cataloging of endangered plants

and sharing of information that will only make the currently available databases

more robust and responsive to the needs of the scientific and governmental

communities alike.

REFERENCES

http://endangered.fws.gov/listdata.html

- On this site you are able to download a variety of information about plants,

animals, and delisted species throughout the United States. There is no place to add information to the

database. This database is current only

through March 31, 1999.

http://www.epa.gov/espp/database.htm

- Again data available for download on a variety of species with instructions

on how to query the database.

http://www.nbii.gov/index.html

- http://www.nbii.gov/datainfo/metadata/

- This second entry was the only one that I found that encouraged you to submit

data of any kind. They were however

looking for metadata, not observational data.

http://www.envirolink.org/species/oesus.html

- A World Species List (WSL), Animals, Plants and Microbes, Established April,

1994, http://www.envirolink.org/species/, USA

Nonprofit 501(c)3, IRS EIN Number 51-0381202, Richard

Stafursky, mavs@panix.com, Lewes, Delaware USA, Voice phone (302) 645-5592 –

This site has an impressive list of data available, down to the microbe level

for download, again, no way to submit data.

http://refuges.fws.gov/NWRSFiles/General/Query.html

- This site is administered by the Fish and Wildlife Service - National

Wildlife Refuge System. There are

instructions for simple search and advanced query techniques for their

databases.

http://darwin.eeb.uconn.edu/biodiversity.html

- This site is mainly interested in listing biodiversity database information

as well as organizations available for research information.

PARENTHETICAL CITATIONS

National Endangered Species Act Reform Coalition, U.S. Fish

and Wildlife Service.

Extracted from: The California Natural Diversity Database –

Commonly Asked Questions (NDDB questions; Answers.wpd//Rev: 1/26/00).

http://www.dfg.ca.gov/whdab/html/cnddb.html

Manzanita Project website, http://www.calacademy.org/research/library/manzanita/html/

|