Sierra Nevada Red Fox

(Vulpes vulpes

necator)

Claudia Houghton

American River College, Geography 26:

Data Acquisition in GIS; Spring 2002

Abstract: Little is known about this elusive carnivore. It has the precarious province of being both the elusive hunter and an opportunistic panhandler. It was not until the discovery of the study group in the Lassen Volcanic National Park area 10 years ago that researches from U.C. Berkeley, searching for another elusive mountain carnivore, the wolverine, discovered this population of mountain red foxes.

Introduction:

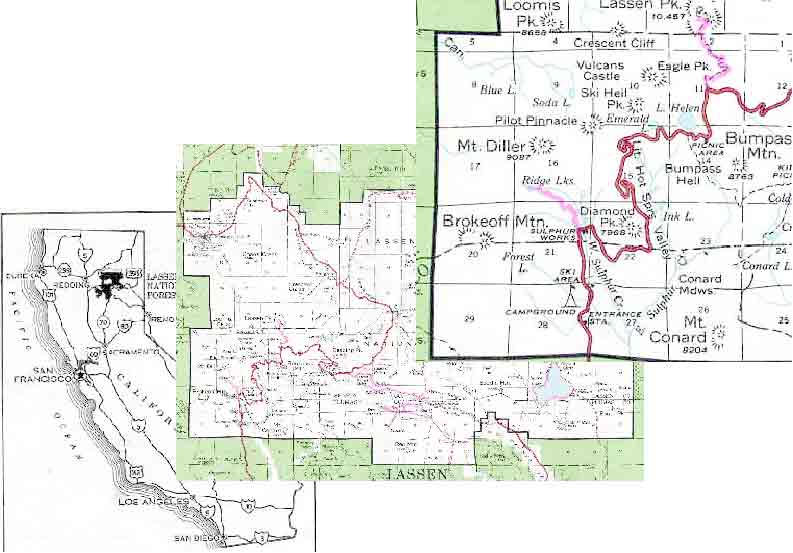

In 1980 California Fish and Game Commission designated the Sierra Nevada red

fox (Vulpes vulpes necator) as threatened. In 1997 a study was began on the

Lassen National Forest and in Lassen Volcanic National Park to assess the

population of the Sierra-Nevada Red Fox. Since 1998 five Red Foxes in Lassen

Volcanic National Park and on the Lassen National Forest have been radio

collared to follow their habits and range areas. Of the five collared three

remain alive. The original male died of natural causes last winter, 2000/2001,

and the original female that was collared was found died of unknown causes in

the snow in the winter of 2000/2001. Her radio collar had a mortality indicator

that led to her remains. The remains that were found suggested that a predator

had taken her. When the study began the hypothesis was that there would be a fox

on each of the major peaks, mountains, in the Lassen Park area. Thus figuring

for a study group of about twenty foxes. This has not proven to be the case,

with only five captures and collars in four years. It looks as if the number of

foxes in this area are much lower than originally though, with only three left

in the study group. There was a reported sighting of a female with a single pup

in the Lassen area in the summer of 2001, but this sighing has not yet been

confirmed. In the winter of 2001/2002 an effort to capture and collar more foxes

and the use of aerial telemetry will be perused by Lassen Park Wildlife

Biologists in the hopes of a larger study group and a confirmation of the red

fox population in the area.

Furbearers, such as the Sierra-Nevada Red Fox in California, are indicator species and are in subsequent decline. If these small fur bearers numbers drop an important link in the ecological niche is broken and the cycle is thrown out of balance. Small carnivores eat a lot of voles, mice, chipmunks and other small rodents. Without small predators these populations can get out of control and the biodiversity of that ecosystem is weakened. If one species is thrown out of balance the whole ecology of an area is thrown off. When this imbalance is man caused it happens at an accelerated rate and that usually influences a very long habitat recovery and in some cases the habitat cannot recover at all. Case in point, the absence of a predator that helps to control rodent populations. The other phase of this study is a genetic tracing of the red fox population in the Lassen area. It is difficult to distinguish between the native Sierra-Nevada Red Fox subspecies and the non-native Red Fox subspecies in the Northern Sierra-Nevada Mountains. In the early 1900’s the fox farm at Lake Almanor closed down and released all of their farm bred Red Fur Foxes into the local mountains (Magnuson, 1999). When a hybrid is released into an area with a similar natural species they compete for the same food, territory and mates. One usually looses out. Often the non-native species will displace the native species. The genetic evaluations are to determine if they are true Sierra-Nevada Red Fox, or a mixture of the released foxes and the natural fox, or just a direct line from the released fox population. This is true evidence of mans interaction with nature in a negative way. These non-native domestic species can also bring in diseases that can wipe out the native species. The native species have no tolerance to domestic diseases. The uncertain status of the Sierra Nevada Red Fox in California is unknown. at this time, there are not enough survey efforts being funded to give a conclusive answer.

Background: The Sierra Nevada red fox occurs in scattered locations throughout

the Sierra

Nevada and the Cascade ranges above the 4,000-foot elevation. It is

differentiated from other red fox by its coat. It is a dusty golden gray with

hints of red only around its muzzle and flank. But like all red fox’s it has the

trade mark bushy tail with its distinctive white tufted tip. This characteristic

tail distinguishes the red fox from the coyote and gray fox with their blacked

tip tails. The mountain fox is often confused with the lowland red fox that was

introduced by humans in the late 1800’s. The line of distinction has been drawn

in the elevations of the fox’s home range. The lowland fox occurring below 3000

feet and the native mountain fox occurring above 3000 feet. There have been

extensive studies on fox habits through out the world, all but the elusive red

foxes of California. Perhaps this is due in part to the rugged terrain. heavy

snowfalls and limited access to its territories. Even in the trapping era of the

1800’s the red fox harvest was only about 20 per year. (Joseph Grinnell, 1937)

These counts and the counts of today suggest that the Sierra Nevada red fox has

occurred in low densities for at least the last 100 years, if not historically,

and is in seemingly subsequent decline today.

Background: The Sierra Nevada red fox occurs in scattered locations throughout

the Sierra

Nevada and the Cascade ranges above the 4,000-foot elevation. It is

differentiated from other red fox by its coat. It is a dusty golden gray with

hints of red only around its muzzle and flank. But like all red fox’s it has the

trade mark bushy tail with its distinctive white tufted tip. This characteristic

tail distinguishes the red fox from the coyote and gray fox with their blacked

tip tails. The mountain fox is often confused with the lowland red fox that was

introduced by humans in the late 1800’s. The line of distinction has been drawn

in the elevations of the fox’s home range. The lowland fox occurring below 3000

feet and the native mountain fox occurring above 3000 feet. There have been

extensive studies on fox habits through out the world, all but the elusive red

foxes of California. Perhaps this is due in part to the rugged terrain. heavy

snowfalls and limited access to its territories. Even in the trapping era of the

1800’s the red fox harvest was only about 20 per year. (Joseph Grinnell, 1937)

These counts and the counts of today suggest that the Sierra Nevada red fox has

occurred in low densities for at least the last 100 years, if not historically,

and is in seemingly subsequent decline today.

Conclusion: Comprehensive research projects by researches such as John D. Perrine are in search of the answers to the survival and habits of these fascinating elusive carnivores. How do they find food during winters of severe snowfall, in excess of 30 feet? What is their preferred habitat for hunting and raising their pups? How large are their individual territories? What are their reproductive cycles and how many pups are in a litter? Are they at risk of interbreeding with introduced red foxes? The author provides a solution to problem and/or identifies applications and needs for future research.

References

USDA Forest Service-Sierra Nevada Framework: Environmental Impact Statement www.r5.fs.fed.us/sncf/eis/summary/direction/priority October, 8,2001.

Note: Personal interview, Mike Magnuson Magnuson, Lassen National Park Biologist Mike, Interview October 15, 2001.

John D. Perrine and

Reginald H. Barrett Environmental Sciences, Policy and Management Department UCB

June 30, 2001 Goodchild, M.F. and J. Proctor, 1997. Scale in a digital

geographic world. Geographical & Environmental Modelling, 1(1):5-23.

Literature Cited

John D. Perrine. 2001. PhD. candidate in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management at the University of California, Berkeley, A summery of an article by John D. Perrine.The Sierra Nevada red fox:Mysterious hunter of the mountains

Joseph Grinnell. 1937.

Founder of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California at

Berkeley, Furbearers of California.