USING GIS TO ANALYZE NONFICTION LITERATURE

Author

Information

ALVIN COLPITTS

American River College, Geography 26: Data

Acquisition in GIS; Fall 2002

Abstract

I sit at my desk

each night with no place to go,

opening the wrinkled maps of Milwaukee and Buffalo,

the whole U.S.,

its cemeteries, its arbitrary time zones,

through routes like small

veins, capitals like small stones.

~ Anne Sexton

A hallmark of

good writing is an ability to “transport” the reader to an intended place or

time. Literary works abound with passages which attempt to define space and

time. In fiction, the writer may have an actual place in mind which gives form

to the physical landscape, but artistic license allows for alteration. For the

nonfiction writer, however, place and space must be definite. Their work must be

able to convey precise, verifiable visual images to the audience.

Often,

as an aid to spatial understanding, publishers supplement nonfiction with maps.

Readers are given a basic lay of the land with features, it is hoped, will help

them in their comprehension of the text material. Sometimes the maps are

sufficient. In many cases, if not most, they seem to be woefully inadequate.

Introduction

My project is an attempt to use the tools of GIS

to promote a better understanding of a specific place in a nonfiction work. I

was first struck by the dearth of spatial information presented by supplied maps

while reading J. M. Roberts’ thorough and informative History of the World

(Penguin Books). Fascinated - sometimes overwhelmed - by the density of

information presented, I was somewhat frustrated by the lack of support supplied

by the accompanying maps distributed throughout the pages. Inadequate legends.

Cramped labels. Is that supposed to be a river or a national border? Eventually,

I abandoned referring to the maps altogether.

A nascent understanding of

GIS has led me to consider ways in which this technology can enhance nonfiction

literature. Surely, better maps can enlighten the reader, but I began to wonder

if the application of GIS to the process would yield greater results. Challenged

by the possibilities (I have yet to find anything that discusses a GIS treatment

of literature), I set my wheels in motion.

Background

My next

task was to determine a source for the project. What book should I develop the

map from? I wanted to choose a piece which would allow me to explore a place -

or places - that I had never been to before. I desired to learn about an area of

the country I was not familiar with. I figured this factor would add a measure

of intrigue to the task. After much consideration, I settled on William Least

Heat Moon’s Blue Highways. Published in 1983, the book recounts the author’s

solo trek around the United States. Keeping primarily to backroads (the “blue”

highways on old highway maps) rather than interstates, Heat Moon takes 3 months

to round the country, traveling over 13,000 miles and visiting 39 states ( by my

count). My wife and I had read the book together on a road trip from Southern

California to Bryce Canyon National Park and back. We were captivated by the

author’s tales of obscure little places with names like Nameless (Tennessee),

Dime Box (Texas), Hungry Horse (Montana) and Humptulips (Washington). The

romantic in me swelled with visions of cross-country travel to similar

off-the-beaten-path locales. The piece was chosen for another, more pertinent,

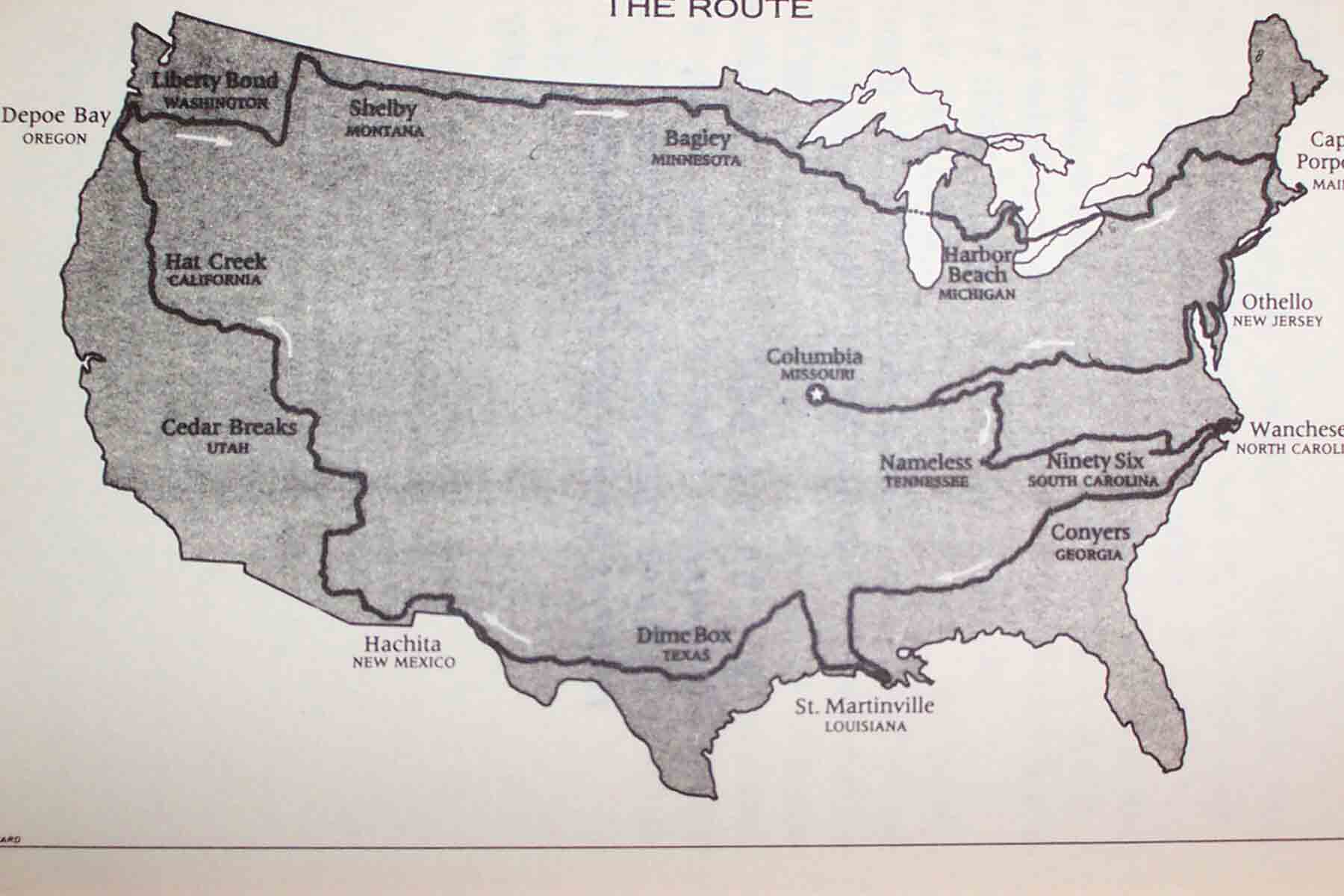

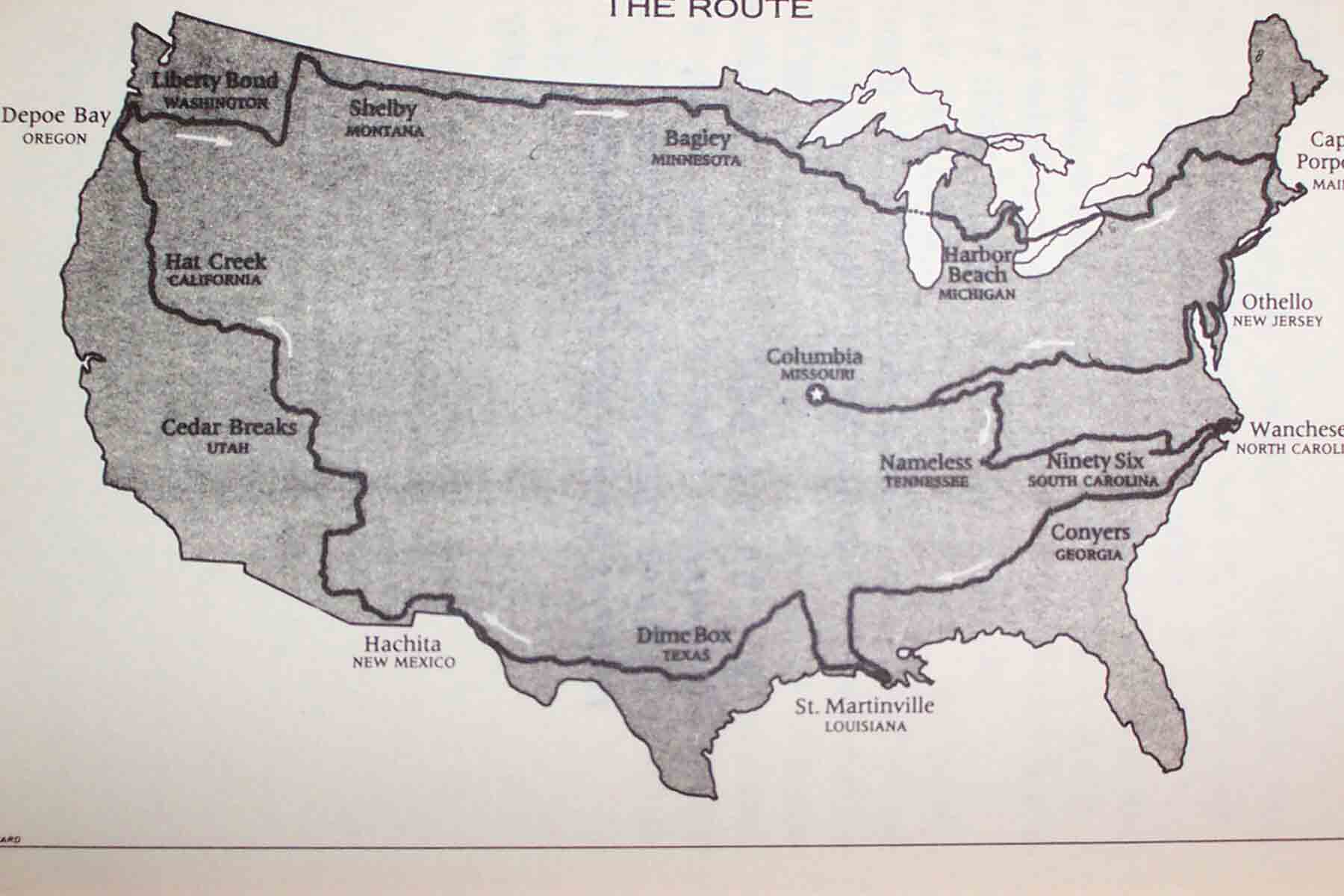

reason: there was only one map in the entire book. One map!

And not a very good one, as you can see. We were

fortunate to have our road atlas with us, but it was lacking somewhat as well.

“Where exactly is The Palouse?”, I remember my wife asking, as we read of the

author’s travels through eastern Washington. I shrugged. “ I don’t know. I

thought that was the name of Washington State’s football stadium”, I replied. My

initial intent was to create a map sketching each blue highway Heat Moon drove

along. Within each line segment, I would locate points representing the various

towns and other landmarks he had mentioned with references to their respective

page numbers.

As I began creating the database from the book’s index, I

realized the immensity of the task I’d undertaken. A quick count indicated there

were more than 500 point locations mentioned by name. Coupled with 13,000 road

miles, my construct, I concluded, was going to be far more complex than anything

I could handle in one semester. I would have to scale the project back. I

decided to focus on only one state.

If you are what you eat,

a visit to North Carolina could

make you a very interesting person.

~ North Carolina Travel Dept.

I quickly settled on North Carolina. For reasons that are hard to

identify, let alone explain, the Tar Heel State has always held me in thrall.

With a 4-year old and a newborn (2 weeks new when we’d left Southern

California!) in tow, we had set off this past spring on a six-week RV trip

across the country. We reached our eastern culminate with a one-week stay in

Asheville, exploring the western part of the state.

I was pleased to

discover I had not crossed paths with Heat Moon. This met my condition that I

had not been to the place I would be studying. Entering North Carolina from

Tennessee on Rte. 321, he spends almost 50 pages touring the eastern half before

exiting for South Carolina on SC Hwy. 34.

Again, I became concerned

about the scope of my study. Could I prepare a quality GIS-based examination of

so great an area? A key feature of GIS is an ability to deliver depth to spatial

analysis. I feared I would not be able to do so within the alotted time. For the

sake of maintaining peace of mind, I decided to narrow my subject once again.

The first third of the North Carolina narrative is indistinguishable in

its discussion of place. Mainly, it is about the author searching for a dead

relative’s burial place. On page 89, however, I began to sense I was on to

something:

Out of Greenville, on Route 32 just northeast of the road

to Pinetown, gulls dropped in behind the

Farmalls and poked over the

upturned soil for bugs, and the east wind carried in the smell of the

sea.

People here call the dark earth “the blacklands”. Scraping, scalping,

bulldozers were clearing fields for tobacco and pushing

the pines into big

tumuli; as the trees burned, the seawind blew smoke from the balefires down

along the highway

like groundfog. Trees burned so tobacco could grow so

tobacco could burn. But where great conifers still stood,

they cast

three-hundred-foot shadows through the morning, and the cool air smelled of

balsam… (89-90)

Studying a reference map I had recently ordered

online - courtesy of the North Carolina Dept. of Transportation - I picked up

the author’s scent on NC State Road 32 (out of Washington, NC actually) and

navigated over the narrative. SR-32 brought us into Plymouth, where we filled

the tank and conversed with an old-timer about timber, tobacco and The War

Between the States (90-92). Out of Plymouth, we headed east on State Hwy. 64 and

onto the tidewater peninsula which sits between Albemarle Sound on the north and

the Pamlico River to the south. I was taken with how my map had brought out the

text:

Cypress trees cooling their giant butts in clean swamp

water black from the tannin in their roots, the

road running straight and

level and bounded on each side by watery “borrow ditches” that furnished soil to

build

the roadway. Ditches, road, trees - all at right angles. The swamp

growth was too thick to paddle a greased canoe

through, and, although

leafless, the dense limbs left the swamp without sun.

Then, precipitately,

the vegetable walls stopped, and the wide Alligator River estuary opened

to

sky and wind. Whitecaps broke out of the strange burgundy water. As I

drove the long bridge over the inlet, a herring gull,

a glare of feathers,

put a wingtip a few feet to the left of Ghost Dancing (the handle given by the

author to the

Ford Econoline), and, wings steady, accompanied me across. (92)

Crossing the Alligator, I determined, had brought me at last

to my destination: Dare County. Consisting of a mainland

peninsula-within-a-peninsula, an island (Roanoke) and a section of a unique

stretch of land commonly known as the Outer Banks, I felt Dare County presented

myriad opportunities for a GIS project. I wasn’t sure of what I would do, but

now, at least, I knew where I would do it.

Methods

As

previously mentioned, there is no specific instance - that I was able to find -

where someone has discussed using the tools of GIS to develop mapping strategies

for a specific piece of nonfiction literature. Inherent to the basic nature of

GIS is the need to deal with fact. This would rule out its use with fiction,

naturally; though I suppose perhaps someone with an extremely creative mind

could use the technology to create maps for a non-existent place. George Lucas,

the creator of Star Wars, comes to mind as a possible candidate.

I did,

however, come across a book, which examined how GIS is being used to study

history - the lifeblood of most, if not all, nonfiction. Past Time, Past Place:

GIS for History (Knowles, ed. 2002) catalogues a dozen cases in which the

technology is being utilized to enhance our understanding of the past. Topics as

wide-ranging as the Salem Witch Trials, the Civil War and the Depression-era

Dust Bowl phenomenon are given modern-era treatment using the tools provided by

GIS. Historical maps are given over to rubber sheeting, static data sets are

presented in a geospatial arrangement and data-gathering capabilities, primarily

GPS systems, are used to pinpoint features which may have been obscured by the

passing of time.

The case studies, I felt, closely paralleled what I was

trying to do. In his geospatial analysis of New York City census data for

factors of race, immigration and ethnicity throughout the 20th century, Andrew

Beveridge makes reference in passing to Jacob Riis’1890 landmark sociological

study, How the Other Half Lives (p.75). Here, Riis examined conditions in which

the poorest classes of people survived in New York City as well. I’m certain a

fusion with Beveridge’s GIS output would yield insights into How the Other Half

Lives not otherwise possible.

My embarkation point, however, differs

somewhat from those in Past Time, Past Place. As a travel narrative, Blue

Highways is not really about an historic event - though it is historical (I date

the trip at some time between 1975 and 1983). I’ve often wondered what Heat Moon

would think of my attempt to quantify his experience. Well, whatever his

opinion, I soon came to the realization that no amount of time searching the Web

was going to yield a database file of his journey. The book would just have to

fill this requirement. And, the “geoprocessing wizard” that I am, that theme had

just been clipped by a Dare County shapefile!

I knew at once my focus

would be on the Outer Banks. How peculiar this landform that rims the coastline?

Running from the Virginia south for some 175 miles, the strand maybe reaches two

miles across at its widest point. The Outer Banks are home to Kitty Hawk. Much

of the Banks compose the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, one of the nation’s

more popular national parks. I set about learning their environmental

characteristics, endeavoring perchance to understand how the Outer Banks formed,

and how they continue to exist, given the frequent hurricanes which batter the

Atlantic Coast.

Additionally, I began investigating those magnificent

sentries of the Outer Banks - the lighthouses. If time permitted, I wanted to

create “hot links” in Arc View, which would allow viewers to click on an icon

for live views from the respective lighthouses. I considered attempting to

create a GIS model of the moving of the Cape Hatteras lighthouse in 1999. The

208-foot giant was moved 2,900 feet inland because it was feared that further

erosion might topple the structure into the surf (note: originally built in

1870, the monolithic-like structure was 1,500 feet from the water at that time!)

Unfortunately, my grand plans were thwarted by the realization that Heat

Moon never visits the Outer Banks. Sure, he leaves the mainland and heads toward

my Shangri-La, but he only goes as far as Roanoke Island (say it ain’t so!)…

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could

not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as

far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

~ Robert Frost

I realized I had reached a crossroad. I could either devote myself

to continuing on the Banks or stay true to the text. I determined here the

project would be about the journey rather than the results. I felt it was more

important to stick with my original premise.

Feeling somewhat stranded

on Roanoke Island though, I began to look around. Heat Moon gives no explicit

reason for having come here, but through the pages I began to develop a fondness

for the place. The first English settlement in the New World, Fort Raleigh, was

established along the island’s north shore (Dare County, it is said, is named

after the first Anglo child born in the United States). Roanoke’s two formal

towns, Manteo and Wanchese, were named for the first two Manitowocs taken by the

explorers back to England to be trained as interpreters.

I began to

ponder. As a subject, the thought of analyzing an island sounded appealing. The

land-type has clearly defined boundaries, by nature. Points, lines and polygonal

features are abundant on a developed island like Roanoke. I hoped this would

mean data could be gathered quickly and efficiently in an easily definable

format. I was ready to go.

The fact I was 3,000 miles from my study area

would limit my access to data. My sole option, I felt, was to search the

Internet. I was able to download general shapefile and database data for Dare

County from the state’s Department of Transportation website (www.ncdot.org

). However, I had a great deal of difficulty finding a

shapefile which provided an outline of Roanoke . Moreover, when I did locate a

source for this essential component, my lack of ability with Arc View 3.2 meant

I wasn’t able to georeference the dataset with my existing one. Basically, the

outline of Roanoke Island was in eastern Tennessee!

At this point,

feeling the pressure of time constraints, I chose to scrap everything I had done

in Arc View up to this point. I thought I would be able to avoid repeating the

projection error issue by pulling all my data from the same location. I was

quite fortunate on this front. An orderly data dataset was accessed via the US

Census Bureau’s TIGER/ Line network.

Results

Analysis

I’m afraid I’ve fallen quite short on

this front. Due to the time factor and a general inability to master the tools

of Geographic Information Systems (for now!), I wasn’t truly able to bring about

a geospatial understanding to Blue Highways. I realize I spent far too much time

reading and deciding where to focus my attention, rather than quickly settling

the matter and moving on to data acquisition and analysis.

Hindsight has

also allowed me to consider how I might have treated Roanoke Island. Perhaps I

could have examined population trends in Manteo and Wanchese in the past 20-30

years since the book was written, or examined land-use issues unique to the

island. I had hoped this would be possible, as I found a map that defined the

marsh areas of Roanoke. There was, however, no accompanying dataset and I was

not able to incorporate the image into my Arc View session. Additionally,

knowing the software package more definitely would have allowed me to pinpoint

locations from the text material in the display. I had tried to do this by

indicating the position of Fort Raleigh on the island, but I wasn’t impressed

with the result.

Conclusion

Alas, this project has allowed

me to understand what needs to be considered in applying GIS technology to

nonfiction. Rather than being obsessed with determining where my analysis would

take place, I believe it is more important to look for what can be examined with

GIS. I am sure future projects in the GIS industry, similar to those chronicled

in Past Time, Past Place, will prove vital in our understanding of social

evolution.

Likewise, I hope that with greater understanding of GIS

applications, my desire to develop a model for narrative nonfiction will mature.

I truly sense based, on this research, that GIS can advance the quality of

cartographic output for print works. I’ve not yet resolved the issue of how to

deliver this vision in a broad format, but I’ll cross that bridge when I come to

it…

The man who says it can’t be done,

is interrupted by the

man doing it.

~ Unknown

(from a sticker on our refrigerator when I was a

kid)

References

DATA:

US Census TIGER/Line Files

QUOTES:

-All quotes were found at www.bartleby.com

Emerson,

Ralph Waldo “The Young American”: Nature, Addresses, and Lectures

(1849)

Referenced from The Columbia World of Quotations. 1996

Frost,

Robert “The Road Not Taken” from The Poetry of Robert Frost.

Henry Holt

& Co., 1920

Referenced from The Columbia World of Quotations.

1996

North Carolina Travel Department “If you are what you eat…” From

an

advertisement in Sports Illustrated, 31 Mar 1986

Referenced from

Simpson’s Contemporary Quotations. 1988

Sexton, Anne “And One for My Dame

(poem)”

Referenced from The Columbia World of Quotations.

1996

REFERENCES:

Heat Moon, William Least. Blue Highways. Hall &

Co. (Boston), 1983

Knowles, Kathleen (ed.) Past Time, Past Place: GIS in

History. ESRI Press, 2002