|

|

||

|

Carrie George American River College Geography 26: Data Acquisition in GIS Spring 2003 |

||

|

A

b s t r a c t

|

||

|

Acquiring data for projects that require a GIS component can cross the spectrum from easy to hair-brained. But once the data is in hand, whats to be done with it? Beyond the simply making maps or doing simple analysis, thought must be given to the timeframe of the data's usefulness. Acquiring data from in-ouse non-technical staff poses challenges in it's level of attribution and accuracy, not to mention making it work for a project. This excersice was intended to loosely run the process of project data acquisition for communication to non-technical staff in a "brown-bag" setting. |

||

|

I

n t r o d u c t i o n

|

||

| Obtaining

GIS data for any project can be at times a challenge. Coming into a project

well after it's inception can be an organizational mess. My previous GIS

work experience has been with a federal agency that takes great care in

data accuracy and standards while maintaining a base data archive containing

most everything GIS staff could ask for. Maintaining the base data "nuts

and bolts" thus makes other analysis easier. Moving into a private

sector job with a young GIS department creates new challenges in acquiring,

maintaining and paying for base data per individual project. Therefore,

the benefits GIS staff involvement early on in any project will only prove

to be beneficial in the months and years to come. Focusing on an ongoing

project in the South Lake Tahoe area, I will review the process of acquiring

data internally and externally to show varying degrees of acquirable data

and it's usefulness. |

||

|

B

a c k g r o u n d

|

||

|

The

Upper Truckee Marsha area lies at the southern end of Lake Tahoe, surrounded

by the town of South Lake Tahoe. Project staff are currently examining

the effects of urban encroachment on the marsh and its relationship

to impacts of municipal infrastructure. Previous to my involvement with

the Upper Truckee project, digital topoquads (DRG's) and some aerials

were obtained along with staff developed shapefiles and coverages. Initially,

I was charged with reeling in all GIS-specific project information to

for assessment and later integration to a GIS network repository.

|

||

|

M

e t h o d s

|

||

|

After

the initial organization of data to a central location, I attempted

to ascertain what data was available to staff. Some project members

were unaware as to what had been collected, what state of creation data

was in and, most importantly, where data was located. At this point,

communication is vital while GPS data is continuing to come in from

field staff and office staff work on report generation.

Happily, most base data is free for the taking. While it may not be practical to keep a large number of data sets stored on a personal hard drive, it is practical to keep every resource book marked on a web browser for easy retrieval (see data links for a list of resources). Government agencies typically have a File Transfer Protocol established containing public domain data. Federal agencies, such as the Bureau of Land Management's California and Nevada State Office, provide public domain, documented datasets such as hydrology, transportation and political boundary information which were obtained for base map production. Topographic maps and digital elevation models are also free web assets. Comparing change over time of the Upper Truckee marsh area is essential for staff assessment and historic aerial photographs were obtained for evaluation. Aerials are by no means cheap. If available, it was necessary to have a legacy of aerial information for each decade previous to a chartered fly over in November 2002. |

||

| Most

historic aerials for this project came from the Whittier College Collection.

Parcel information is highly important to the project. Before my arrival, project staff was attempting to digitize parcels from plat maps into the GIS environment. This not only created poorly attributed files, but poorly digitized files. Calling the assessors office saved digitizing man-hours and provided valuable information about each of the parcels that comprise the study area. This data was not free, however, but well worth the inexpensive cost. |

|

|

|

R

e s u l t s

|

||

|

|

||

|

F

i g u r e s , M a p s

|

||

|

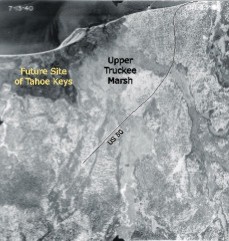

Aerial photograph taken July 1940. The Upper Truckee Marsh is top, center. Tahoe Keys and Marina are not yet in existence at the time of this flight. |

|

|

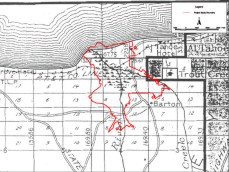

Pictured is a 1914 plat map of the Upper Truckee Marsh region. For analysis, The map was georeferenced in the GIS and then compared to the study boundary (shown here in red). The scale of the study boundary is not exact, an example of non technical staff "guessing" at placement. |

|

|

A

n a l y s i s

|

||

|

The

most difficult part in stewarding the Upper Truckee project data is

the acquisition of spatial layers digitized by staff. More often than

not, I find myself revisiting original survey data (e.g. master title

plates, grid sheets) and reconstructing shapefiles. Before my being

brought on board as a GIS Assistant, spatial data files were poorly,

if at all, attributed. This is starting to change as I ask very little

from my co-workers who are not proficient in GIS. Setting minimal standards

for table fields such as "COMMENT" and "SOURCE"

can sometimes provide enough information to at least track down the

person with the answers.

|

||

|

C

o n c l u s i o n s

|

||

|

Much

more work need to be done to convey the message of follow-through with

GIS. Acquiring information is important, but acquiring meaningful well-attributed

information is beneficial. For historic aerial geo-referencing, metadata

creation (e.g. flight number, plate number, date) is absolutely essential

if hard copies are lost.

This project was meant to challenge my own approach to being thrown into a project and the process of recognizing the steps of better GIS data acquisition internally and externally. After final submission, this project will serve as a reference point for presenting keys to smoother data acquisition/creation/management at work. The hope is to communicate clearly, using a common dialogue, to non-GIS staff the benefits of pre project planning and documentation. |

||

|

R

e f e r e n c e s

|

||

|

Fairchild

Aerial Photography Collection at Whitter College. Source: http://www.whittier.edu/fairchild/home.html.

Accessed: 2003.10.05

Popoff,

Leo. 2000. Basin Watch: The Upper Truckee River Basin's Underground

Flow. |

||

|

D at a |||

L i n k s

|

||

|

|

||