IN SEARCH OF GLACIAL ICE WORMS Finding Accessible Ice Worm Habitats in Southeastern Alaska | |

|

Author Ethna McCartan American River College, Geography 350: Data Acquisition in GIS; Spring 2004 Contact Information (email: stan4mom@aol.com) | |

|

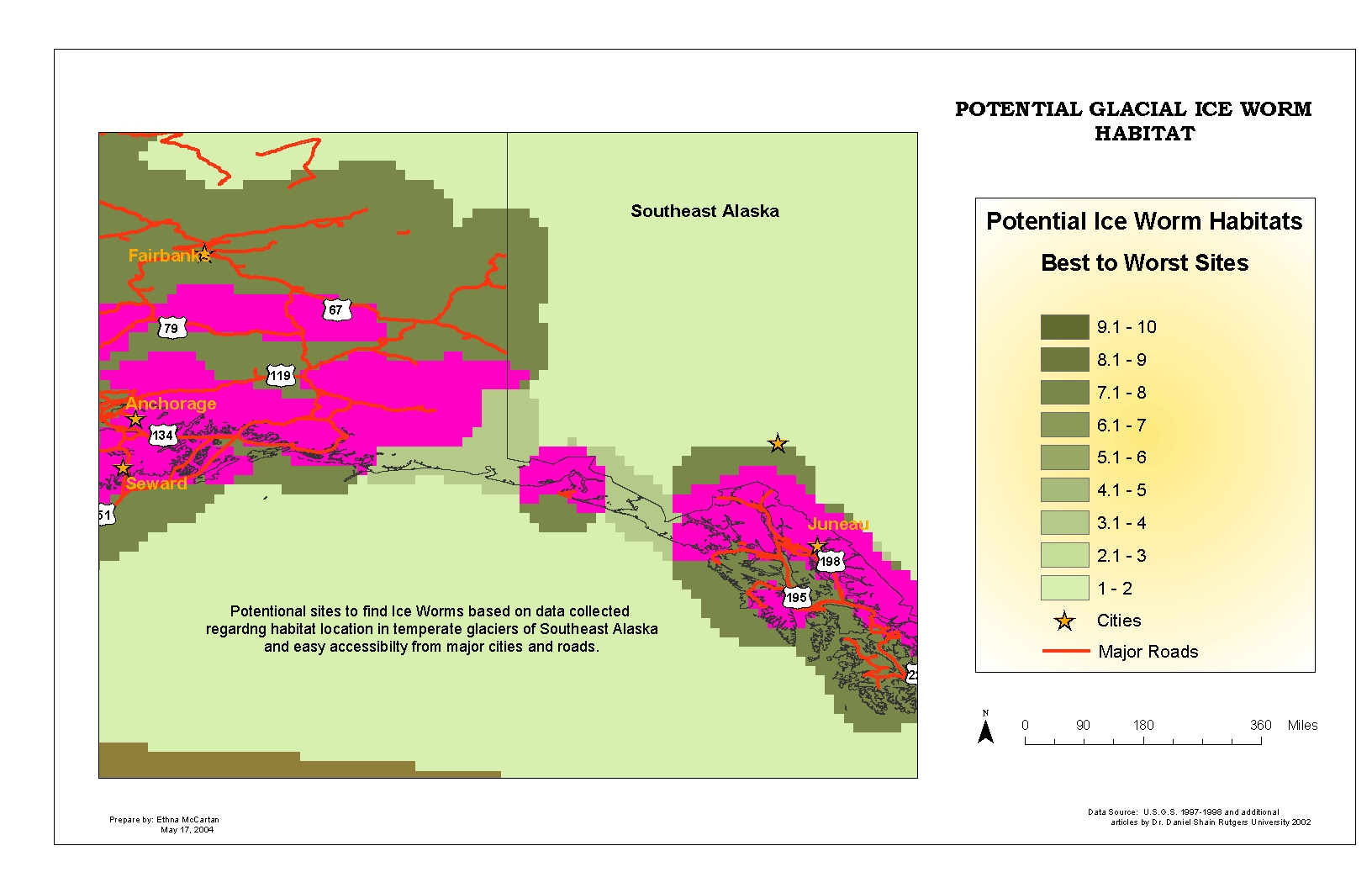

Abstract Spatial analysis can be used as a tool to display the location of accessible sites for specialists to study glacial ice worms. This paper describes the process used to build an access location map and the discoveries along the way. | |

|

Introduction There is a growing concern about global warming all over the world, which could be a definite problem for a small creature that inhabits a limited area along the edge of glaciers. The ice worm, which is a relative of our garden worm, inhabits the fringe of these frozen masses and has peaked the interest of scientists and geographers alike in the last few years because of where as well as how it lives. By studying how these little string like creatures evolved as well as how they survive and exist in a harsh environment could provide breakthroughs in space travel, tissue preservation and perhaps even insight into the chance of life on other planets. But first they have to be found. So where are the most accessible places to study these animals? | |

|

Background Since very little is known about the ice worm it became important to research by Internet articles the physiology, morphology and habitat of this small animal. Until recently, the ice worm was considered a legend. The first reported sighting occurred in 1887 by George Frederick Wright a glacial geologist and no other official sightings were noted until about 1977. In the last five years all that has changed. Dr. Daniel Shain of Rutgers University has been digging in the snow and ice to figure out what ice worms are all about. Ice worms are 1 cm long dark brown or black little worms that live in colonies on the edge of glaciers. The density of these colonies can be a few hundred thousand to 20 million worms. They are the same physical structure as earthworms, segmented with bundles of setae (hairs) along the bottom of their bodies for moving. There are a number of sensory organs at the anterior end, which are still a mystery as to their purpose and a large pore on top of their head whose function is unknown but there is speculation that is excretes some type of mucous to protect it or lubricate itself (for traveling ease). The mouthpore is as big as the worm is wide (about 1 mm or 1/32"). They have no eyes but respond to light, dark and heat. During sunlight hours they will burrow as deep as three to six feet into the glacier thus the scientific name Mesenchytaeus Solifugus, sun-avoiding worms. They are intragranular which means they travel between grains of ice and when shadows fall and darkness comes the glaciers are covered with little slinky animals that look like pieces of string. They are one of a small number of creatures whose entire life cycle is spent in ice and at this time there is no information as to how long they live.  Their habitat is located on glaciers in southeastern Alaska, the Coastal Range

of British Columbia and Washington State as far south as Mt. St. Helen, which has

a cloudy climate. These are considered temperate glaciers and are very well suited

to the ice worm. This worm is a great indicator for the existence of a glacier

edge under snow since no worms will travel more than 10 meters from the ice.

In these types of glaciers meltwater pools, slush, and streams are found in and

on the glacier year round. These are attractive sites for the worms, not too

cold not too hot. The ideal temperature to live in is 32° F but if the temperature

goes over 40° ice worms will die and turn to mush. If the temperature drops below

20° F they will turn to popsicles. Ice worms have a varied menu. They graze on

snow algae, pollen grains and fern spores during the evening and night hours.

These creatures have little to fear except perhaps an occasional bird. There is

however one threat to their existence and that is global warming which creates

glacial recession. So why should we study ice worms? Their metabolism revs up

at a temperature when most animals would shut down. They have evolved unique

ways to store and produce energy on a celluar level and they could be studied

to isolate the gene responsible. Finally there is evidence that a major change

occurs in the critical enzyme that makes fuel. If this could be harnessed there

could be breakthroughs in space travel, advances in tissue preservation for

organ transplants and insight into possible life on other plants. So now that

we know something about ice worms we need to find them.

Their habitat is located on glaciers in southeastern Alaska, the Coastal Range

of British Columbia and Washington State as far south as Mt. St. Helen, which has

a cloudy climate. These are considered temperate glaciers and are very well suited

to the ice worm. This worm is a great indicator for the existence of a glacier

edge under snow since no worms will travel more than 10 meters from the ice.

In these types of glaciers meltwater pools, slush, and streams are found in and

on the glacier year round. These are attractive sites for the worms, not too

cold not too hot. The ideal temperature to live in is 32° F but if the temperature

goes over 40° ice worms will die and turn to mush. If the temperature drops below

20° F they will turn to popsicles. Ice worms have a varied menu. They graze on

snow algae, pollen grains and fern spores during the evening and night hours.

These creatures have little to fear except perhaps an occasional bird. There is

however one threat to their existence and that is global warming which creates

glacial recession. So why should we study ice worms? Their metabolism revs up

at a temperature when most animals would shut down. They have evolved unique

ways to store and produce energy on a celluar level and they could be studied

to isolate the gene responsible. Finally there is evidence that a major change

occurs in the critical enzyme that makes fuel. If this could be harnessed there

could be breakthroughs in space travel, advances in tissue preservation for

organ transplants and insight into possible life on other plants. So now that

we know something about ice worms we need to find them.

| |

|

Methods This project started with a lot of reading and Internet searches. Research helped me set up my criteria. Ice worms are in Southeastern Alaska, they live on the edge of glaciers (within 10 meters of the edge), they prefer wet glaciers. After finding out as much as possible about the ice worms the next step was to set up what I needed to complete a map showing where the most accessible locations would be. The next step was to find the necessary files to create a drawing in spatial analysis. That would require an Alaskan shp file, modern glacier shp file, roads shp file, cities shp file and a digital elevation model of the Southeastern section of Alaska. That was a real task! Unlike the rest of the United States Alaska has an unusual file and setup. Shapefiles and DEMs were hard to find. Days later I discovered Alaskan Geospatial Clearinghouse and found the files to help me with my task. After bring in all the files I set about my job of creating a new map. Converted files to raster, and set up to analyze the distance to roads, distances to cities, distance to glaciers. Reclassified each of these and was about to do my slope analysis when lightning struck. The DEMs were all DEM.bil which is a drawing. Back to the Internet and found subsitute for my DEM file and again catastrophe struck. The USGS files were retired files and had no metadata associated with them. After several hours of trying to make the DEMs work and due to time constraints I decided to plow on and create a map without considering slope. |

Results The result of the project was knowledge of a life form few people know about and identifying possible locations to access and study ice worms. By reading I was able to set up a criteria for location. Ice worms are found in abundance on Southeastern Alaskan glaciers, 10 meters from the edge of those glaciers, found only during summer, spring and fall, how they live, what they eat and what they look like to be able to identify them. As far as the map is concerned the areas can be identified but without the detail I was hoping for in the map. |

|

Figures and Maps Southeast Alaska | |

| |

|

Analysis The results were mixed in success. Lots of information on ice worms and was very successful as far as identifying where they could be found. However, with the difficulties in obtaining DEMs the task could not be completely finished in the time alotted. I had written and e-mailed a number of people at USGS and Alaskan Geospatial Clearinghouse but what I was asking for could not be sent to me in time if at all. Mr. Brown at USGS is still hopeful he will find a DEM I can use. The best access areas are not showing on the drawing in spatial analysis since slope could not be part of the project. Slope is definitely a requirement since this drawing was to show easily accessible areas to find ice worms. Mountain peaks do not fall into that category. | |

|

Conclusions To complete this project I will need a DEM for the Southeastern section of Alaska. Once that information is obtained it is just a matter of going through the spatial analysis for slope. One other problem I encountered during the analysis part of the project was cell size. They were a little large and I had to redo some of the spatial analysis work in order to complete the final portion of the project. If someone were to ask what was the hardest part of this assignment I would definitely say finding the information. It took a great deal of time and energy on the net to find sites with the workable information I needed. | |

|

References

Glacier Macroinvertibrates, Http://www.nichols.edu/departments/Glacier/bio/chapter4.htmIce worms and Their Habitats on North Cascade Glaciers, Paula Hartzell, 2003 Ice Worms Article #53, T. Neil Davis, Alaska Science Forum, April 5, 1976 Ice Worm Habitats Article #391, T. Neil Davis, Alaska Science Forum, April 18, 1980 Students Probe Peculiar Ice Worms in Alaska's Glaciers, Hillary Mayell, National Geographic News, January 28, 2002 An artic mystery, Caroline Yount, Rutgers Focus, September 29, 2000 Studying the mysterious ice worm, Scripps Howard News Service, Augusta Chronicle, February 5, 2002 Molecular and cellular development of annelids, Daniel H. Shain Asst Professor, Rutgers University http://www.lifesci.rutgers.edu/~molbiosci/Professors/shain.html Alaskan Geospatial Clearinghouse USGS |