|

Title An Investigation in to State and Local Practices |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Author

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Abstract

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Introduction

California, beginning in 1946, was the first

state that required prior sex offenders to register with local law

enforcement agencies. With the

passage of the Jacob-Wetterling Registration Act in 1994, every state was

finally required to establish a sex offender registration and tracking system

by 1997. Failure to do so would

result in a state losing up to 10% of their Byrne Memorial State and Local

Law Enforcement Assistance funding. In 1996, the Jacob-Wetterling Act was

amended to include implementation of the Megan’s Law community notification

statute. Despite California being the first state to

require sex offender registration, the accuracy of the registration program,

the usefulness to law enforcement agencies and the general public, and the

accessibility to the public are all near dead last among the 50 states. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Background

Implementation of

community notification laws vary state by state and each state differs as to

the methods used and information available to the public. Some states

proactively inform the community of the presence of offenders and other

states merely make information available to citizens upon request. At one extreme, states (like Florida)

provide detailed information, maps, or photographs on websites accessible to

the general public, and other states (like California) require the public to

go to a law enforcement agency to see a more limited amount of data. The difference reflects the fact that

there is no national standard to guide the practice of community

notification. Intended Benefits Community notification laws have been

enacted in response to public demand. There is, as yet, little empirical

evidence of their impact. Accordingly, most benefits of community

notification are more accurately described as expectations. Proponents of

community notification suggest the following benefits: The Right to

Know. Community residents,

and parents in particular, have the right to know if a potentially dangerous

person is living in their neighborhood. Public Safety. With knowledge that a person with a history

of sexually abusive behavior lives nearby, citizens can better protect

themselves, their children, and their neighbors’ children. Supervision

and Prevention. Community

notification alerts prior offenders that the larger community, not just law

enforcement, is monitoring them to prevent further offenses. Community

Involvement. Community

notification offers the opportunity for residents to increase collaborative

efforts to promote public safety through the sharing of information and

education. How Community Notification Works Federal law has allowed wide latitude in

fashioning notification processes. Some states centralize the establishment

of guidelines and reporting at the state level with review boards to assess

and classify each offender, the method and extent of notification being on a

case-by-case basis. In some states,

notification is only for high-risk offenders or offenders who have committed

crimes against children. In others, no distinction is made between the types

of sex offenders and all are subject to notification. And some states allow

local jurisdictions to assess offenders and determine the method and extent

of notification; California being in this category. Typically, the information provided includes

an offenders’ name, photograph, age, crime description, and the age(s) of

their victims. More detailed information, such as home or work address, is up

to a local jurisdiction. In Louisiana, the law mandates that sex offenders

themselves must notify the communities they live in of their presence by

sending a card to community members within a three block (in urban areas) to

one-mile (in rural areas) radius, and by placing advertisements in two local

newspapers that inform the community of their presence. Depending on

jurisdiction, residents can receive notification that sex offenders are in

the neighborhood through letters, posters, public meetings, or

radio/television press. Depending upon the state in which they live, citizens

can also obtain information by contacting local law enforcement agencies by

mail, telephone, or the Internet. Two-thirds of notification states,

including California, have guidelines and procedures written into state law. Almost every state has established a

multi-tier “risk” system to identify the most predatory, dangerous offenders.

While there is no perfect risk assessment for all offenders, an assessment

assists to identify offenders with violent tendencies, target resources to

monitor prior offenders who are more likely to re-offend, and determine the

level and nature of community notification. California uses the following 3 categories: High-Risk – The highest risk offenders who have

previously been convicted of at least one violent offense or a combination of

other offenses. Serious – Rape, sodomy or oral copulation with a minor, sodomy or oral copulation by force, sexual abuse or molestation of a child, felony sexual battery, enticement or abduction of a child for purposes of prostitution, or assault with intent to commit sex offenses. Other – Pornography, incest, indecent exposure,

misdemeanor sexual battery, spousal rape, or juvenile offense adjudicated in

juvenile court. In California “High-Risk” and “Serious”

offenders are subject to public disclosure under Megan’s Law and “Other”

offenders are not. Previous offenders are monitored by

probation and parole officers until they have satisfied the terms of their

sentences, and then are most often not monitored thereafter. Registration

laws vary from state to state and may require that previous offenders notify

the police if they relocate for several years after release to the rest of

there life. In the case of

California, registration is a lifetime requirement. Balancing Competing Interests Prior offenders have to live somewhere and the

community they live in has a right to safety. How can these interests be

addressed in a balanced way? The public often has little understanding of sex offenders, sexual offending, and treatment interventions for these offenders. Some of the most proactive communities have used notification as an opportunity to educate their communities by providing information to address concerns, counter misinformation, quell fears, discourage vigilantism, and offer tools for citizens to enhance public safety. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Results 40 states and the District of Columbia

maintain state-sponsored websites with detailed prior offender data. 5 states (Hawaii, Massachusetts, Nevada,

Rhode Island, and Vermont) have no state or local websites with any prior

offender data. 5 states (California,

Missouri, Oregon, South Dakota, and Washington) have limited or local

city/county websites with prior offender data. Refer to the “State Website Links” section, below,

for a complete list of links.

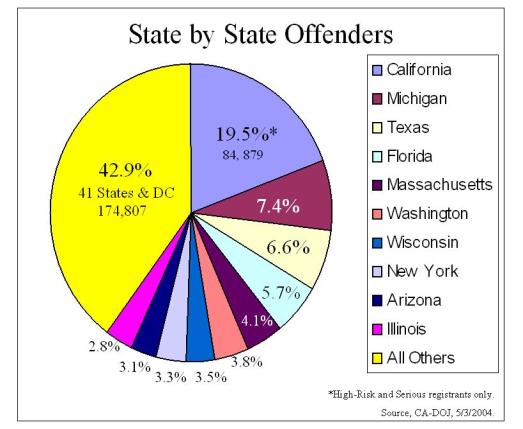

Of the almost 425,000 registered offenders tracked nationwide, approximately 85,000, or 20%, are in California, approximately 175,000 (40%) are in the next 9 largest registration states, and approximately 175,000 (40%) are in the other 40 states and District of Columbia.

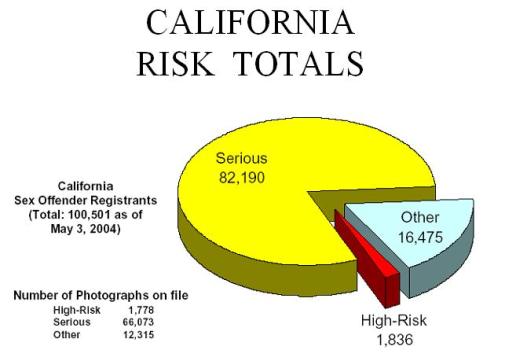

According to the California State Dept. of Justice (DOJ), of the 100,000+ registrants tracked by California, 82,000 are categorized “Serious,” 1,800 are categorized “High-Risk,” and 16,500 are categorized “Other.”

Of the 100,000+ registrants tracked by California, 68,000 are in the community, 17,000 are incarcerated, 12,500 are out of state, and 3,000 were deported. However, this information is incorrect or inaccurate for over 30% of the registrants, according to a 2003 Associated Press audit.

A survey found 18 states were unable to track how many sex offenders were failing to register, or simply did not know. The survey found that up-to-date addresses for more than 77,000 sex offenders are missing from the databases of 32 states, despite the federal law requirement that the addresses of convicted sex offenders are to be verified at least once a year. All states responded to the group's survey, but only 32 were able to provide failure rates. Many of these said they have never audited their sex offender registries and could provide only rough estimates of their accuracy. Of equally great concern was the lack of federal assistance in tracking inter-state movement of prior offenders, let alone a concerted program for sharing or coordinating state data on a national level. Community notification laws have been based

on an assumption that by giving the public knowledge of nearby prior

offenders, it will help prevent further sexual assault. It may be impossible

to gauge the number of crimes prevented by notification laws. There is no

empirical information to support the contention that greater public access

and notification directly results in better prevention, better adherence by

prior offenders to registration, or a better sense of security by the general

public. There is anecdotal evidence,

though, that public interest and pressure on legislative and law enforcement

entities increases the priority placed on enforcement activities by the

responsible state and local departments to maintain current and correct information

on prior offenders. To contrast two state programs -- the

Florida and California enforcement programs. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Florida

In Florida, the state funds and staffs a

coordinated state level program. The

state provides a state-maintained Internet website of prior offenders with

detailed information and photographs.

During 2002 the website received over 5 million hits. With over 27,500

prior offenders required to register with the state, only 4.7% of those are not

in compliance (less than 1,250). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Florida state website allows the general

public to search on a wide-range of criteria and filter the search on over 20

criteria. And the Florida website

doesn’t just keep track of offenders in Florida, it also keeps track of

offenders convicted in Florida who have moved out of state. A search using the criteria of

“Sacramento, CA” resulted in three records of offenders matching! Florida's Department

of Law Enforcement sends letters out each year and has a full-time staff of

11 to keep close track of those that come back. Offenders who don't respond

often get a visit from police.

Several state agencies, including the department that issues driver's

licenses and state identification cards, which sex offenders in Florida are

required to keep, have access to the database and cooperate with law

enforcement efforts to keep the data current. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

California

By contrast, in

California, a weakly coordinated state enforcement program defers enforcement

and reporting activities to local jurisdictions. While the state maintains a comprehensive database of names,

ages, photographs, convictions, and last locations of registered offenders,

it is only accessible through a statewide “900” toll -line or by individual

viewing in police and sheriff stations in larger communities. During 2002, the state-wide “900” Line received 7,468 inquiries by telephone and 1,040 inquiries by mail, which generated a total of 65,974 searches of the VCIN database, and 56,076 members of the public viewed Megan’s Law information at law enforcement facilities, community events sponsored by law enforcement agencies, and at community events sponsored by the DOJ. At the DOJ-sponsored events, 1,980 viewers (over 11 percent) indicated they recognized sex offenders as friends, neighbors, employers, relatives, and in a few instances, people in positions of authority or responsibility over children. Also in 2002, California's Justice Department touted its sex offender database as being a valuable tool for the public -- announcing that information was updated daily and was available in 13 languages. In February 2003 the Associated Press performed an unofficial audit of the California State Sex Offender Registry, the first audit ever done by anyone, and found that the state had lost track of more than 33,000 sex offenders, representing 44% of the then 76,350 who registered at least once since the state required registration in 1946. That does not count the offenders who never registered as required. California is not unique. Even the biggest supporters of Megan's Law say the system

is fundamentally flawed across the nation, since almost all states rely on

convicted sex offenders to check in with law enforcement, and few agencies

provide the resources to follow up.

On average, the non-compliance rate for registration is approximately

24% nation-wide. The difference between the success of Florida and the lack of success in other states appears to be the a state-driven program, legislative support, and technological support that helps the Law Enforcement staff in Florida keep track of required registrants. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Local

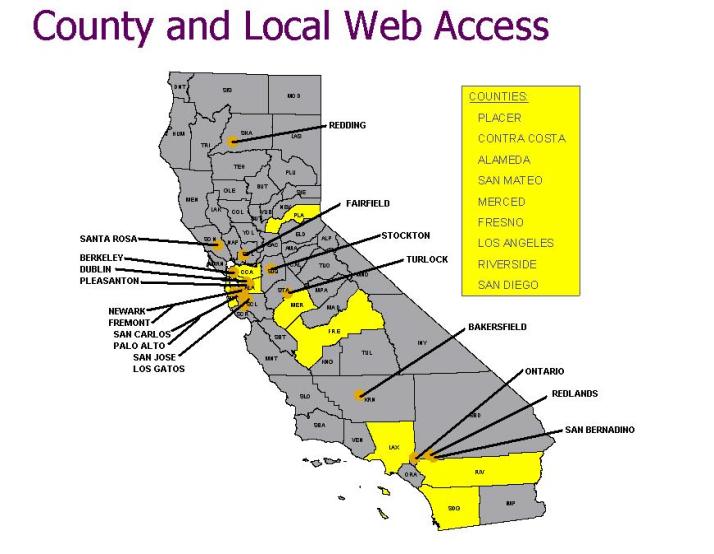

Responses in California Despite the lack of a statewide program, 9 counties and

20 cities in California maintain on-line offender locator maps, photo

listings, or other form of location listings for offenders. Refer to the “California

City and County Website Links” section, below, for a complete list of

links.

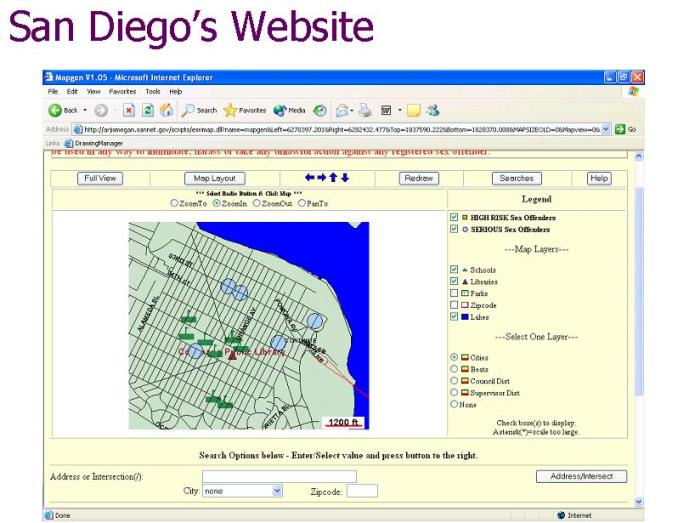

San Diego San Diego has one of the longest existing pin-map websites. The pin-map gives street-level detail with schools, parks, and generalized locations of offenders that maintains statutory required ambiguity. Search features allow users to see the general area where offenders reside and gauge the number of offenders within a relative area. While the maps on the website provide no offender-specific data beyond generalized locations and whether a High-Risk or Serious offender, and while most San Diego zip code areas have over 6,000 residents, making pinpointing of offenders impossible, it provides a way for an initial inquiry by the public that is easily accessible.

Placer County Placer County has a countywide pin-map with

less detail than San Diego. While it cannot be zoomed and searched like the

San Diego pin-map, it doesn’t need such features given the large size of the

county, relatively lower population density, and fewer number of

registrants. The Placer County

pin-map is an excellent example of a simple, yet very informative picture of

sex offender locations. This is in

contrast to the other 45 counties in the state that have no on-line

information other than a few references to the viewable data available at

their local law enforcement agency.

San Jose In December 2003, the San Jose Mercury News decided to publish the photographs, addresses, and other information on 54 “high-risk” sex offenders then registered in the San Jose region – the first time such information was made public in California on any large scale. The fallout from the

article was that three of the previous offenders were identified to have lied

on employment applications that placed them in situations in violation of

their parole. Two previous offenders with multiple previous rape convictions

were living in households with teenage and older females who were unaware of

their past convictions. And one

offender assaulted a woman and was apprehended because of the identification

in the paper. San Jose spends

$600,000 a year on five officers, a sergeant and a civilian analyst who work full-time

knocking on doors, searching the Web and otherwise keeping tabs on their

2,700 rapists and child molesters. In San Jose, police can instantly identify

every known molester living in an area as soon as they learn of a missing

child. In 2002, when a 7-year-old

girl was raped, the department ran a list of every prior offender who fit the

suspect's description and who lived or worked within one mile of the

attack. Every one of them was in

compliance because of the city’s record-keeping system and monthly

audits. When San Jose Police have to

pull a list of suspects, it's accurate. In the wake of the Mercury News article, and in spite of having an already exemplary program, the San Jose Police Department posted a more comprehensive offender web site with names, locations, and photographs of the most serious prior offenders. In 2003, when Megan’s Law information was only available for viewing at police stations, the database was only viewed 360 times in San Jose. In the 3 months since the San Jose Police placed the information on-line, the website has been visited 22,000 times. To date, only one study, performed in the state of Washington, has been completed regarding the impact of community notification on offender recidivism. Research shown for a matched sample of 90 offenders subject to community notification and 90 offenders not subject to community notification (comparable in all other aspects), recidivism in the community notification group were re-arrested sooner than recidivists in the non-notification group. However, the level of recidivism after 4.5 years for both groups was the same, with no statistically significant difference in re-offending between the two groups. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

County

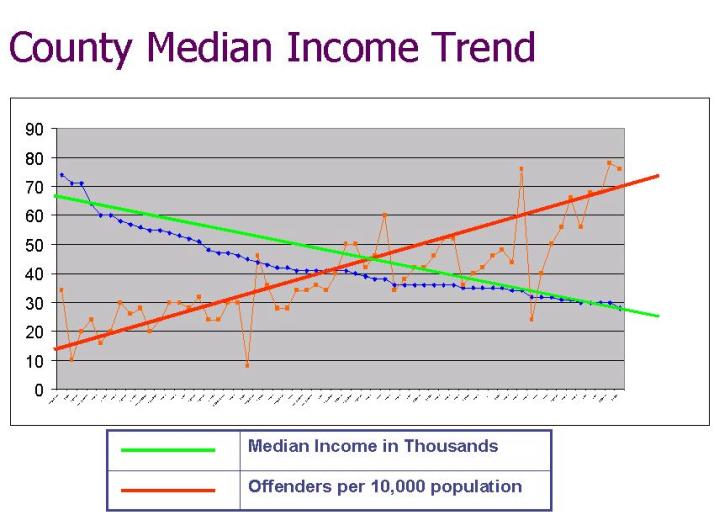

Median Income Trend Per capita offenders populations range from 8 per 10,000 in Mono County to almost 80 per 10,000 (or 10 times as high) in Del Norte County. Regardless of population density, local public access of offender data, and whether or not the local police are more or less vigilant, there was nothing immediately apparent to explain the variance in offenders from county to county. But a comparative analysis

based upon county median income data from the 2000 census provided the

following trend results regarding median income vs. prior offender

population. The results show higher

median income counties tend to have a lower per capita offender population

and a lower median income counties tend to have a higher per capita offender

population.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Challenges to a GIS Solutions

There

are several challenges to providing a GIS solution for Community

Notification. The first relates to privacy issues. Laws in at least five states prevent public access and/or certain information from being released o the public. In California there are the two impediments of the access to the information is restricted to viewing in a law enforcement agency office or controlled setting and the information contains no specific address information on the offenders. This creates a challenge for local jurisdictions that decide to create offender “pin-maps” for public display, requiring the true location of offenders be ambiguously generalized as a large “point” feature. And because of legal restrictions, no information beyond whether the point is for a “Serious” or “High-Risk” offender can be displayed. A second challenge is how to use GIS to provide the offender information. Few jurisdictions have detailed geospatial data, let alone GIS systems in place that can be used. Cost factors involved in acquiring GIS software, creating street-level data layers, and providing search features to find and present offender information in a geospatial presentation is beyond the capabilities of most city and county law enforcement agencies. A third challenge is the accuracy of the offender data and ongoing maintenance. Given that the state of California cannot validate the accuracy of the state data, and the non-compliance rate of registrations, the accuracy and maintenance of the offender data is beyond the scope of most law enforcement agencies. The city of San Jose spends $600,000 per year on their compliance program and estimates for an equivalent state response runs as high as $20 million. And a final challenge is the education required of the public. GIS can provide information to the community, but cannot control how that information is used or prevent its misuse. The challenge is to use information wisely and to advise the public about what they can expect from notification, which does not in and of itself guarantee community safety. The way criminal justice officials carry out public education around these laws and their implementation is likely to contribute significantly to their success or failure of a GIS solution. Legal Challenges

Constitutionality. Community notification has been challenged

in the courts on: ex-post-facto application, issues of privacy, unwarranted

search and seizure, excessive punishment, double jeopardy, and inappropriate

conditions of parole. Notification and information access has been partially

blocked in several states -- California, Massachusetts, and Hawaii for

example. While notification laws have passed legal tests in almost every

jurisdiction, final resolution may ultimately come through a U.S. Supreme

Court decision. The primary debate in this area is whether notification is

viewed as punitive (and therefore subjects the offender to punishment beyond

the original sentence) or regulatory (which is generally considered to be a

permissible action of the state). Vigilantism. Opponents of community notification are

concerned that individuals (and communities) will react aggressively towards

prior offenders. Although such incidents have been rare, vehicles have been

vandalized, offenders and their families have been beaten and verbally

assaulted, and a single incident of a house burning has been documented.

There have been cases where persons that were believed to be prior offenders

have been harassed, only to discover mistaken identification. Law enforcement

agencies have worked to prevent such vigilantism, but individual acts of

violence are always possible. Legal authorities reiterate and enforce

provisions that such action by citizens will not be tolerated. Careful

implementation of notification laws and comprehensive community education

efforts are perhaps the best ways to prevent such acts. Unintended Consequences. Anecdotal evidence suggests that community notification practices have had some unintended consequences. These include a decrease in offender reporting compliance with registration requirements, an increase in plea-bargaining, and a decrease by some child protective agencies in charging juveniles with sexual abuse to avoid subjecting children and adolescents to the scrutiny of public notification laws. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Conclusions From data analysis

- Higher Median Income in a county in California generally equates to a lower

percentage of prior offenders in that county compared to other counties. Community notification has swept across the

nation with strong political and public support. Notification legislation is

a beginning, but it raises many questions still unanswered about how to

achieve community safety. Because

little research has been conducted on community notification issues, limited

empirical evidence is available to support or contradict the presumed

benefits or risks of community notification. Neither community notification laws,

publicly available Internet information, nor GIS are in and of themselves

solutions to this complex problem.

Rather, they are tools in the effort.

Whether or not a GIS solution exists at state or local levels is not

going to solve the problem. However,

the presence of a GIS solution can be indicative of the overall priority that

legislative and judicial entities are placing on the problem of keeping track

of potentially dangerous prior offenders. Community notification laws affirm the

public’s desire for protection from sexual assault and predatory behavior.

However, they do not suggest what communities should do once they are

notified that sex offenders live in their midst. Conflict over privacy and

access is inevitable. For every

person or group that lobbies to restrict dissemination of information,

another lobbies to gain access. Effective implementation must include education

on how community members can protect themselves and their families, protect

prior offenders from potential vigilante behavior, and ensure that

notification practices do not impede the equally desirable goal of moving

offenders into law-abiding lifestyles in the community. There are GIS software solutions for

government entities to make internet-based offender maps available to the

public, while still maintaining a level of location ambiguity to maintain

privacy. ESRI, Digital Map, and

Intergraph produce GIS packages tailored for Megan’s Law that allow law

enforcement agencies to control the amount of data, level of detail, and

ambiguity levels of the map presentations to comply with varying legal

statutes and requirements. Notification laws may provide useful

information to community members but the challenge is to use that information

wisely and to advise the public about what they can expect from notification,

which does not in and of itself guarantee community safety. The way criminal

justice officials carry out public education around these laws and their

implementation is likely to contribute significantly to their success or

failure. After the 2003 AP report, the California

Attorney General pledged to work more closely with local police to update the

database. A year later, in 2004,

improved record keeping determined that more than 12,000 of the

unaccounted-for sex offenders had died, been deported, were back behind bars,

or had moved out of state. But that

still left over 22,000 missing rapists and child molesters, or 33 percent of

the total, all of who are committing a felony by failing to register. Few police agencies in the state can spend

the time and money to provide resources to follow up on missing offenders. While several local jurisdictions in California have taken steps to improve keeping track of prior offenders, finding unregistered offenders, and providing more information to the general public, the accuracy, availability, and accessibility of information still falls far short of information readily available to residents of other states. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

State Website Links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

California City

and County Website Links |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Methods of Analysis Megan’s Law and issues surrounding public notification have been in the news more and more in the last 6 months, especially because of the expiration of the extant Megan’s law provision in the state of California late in 2003 and because several recent sensationalized child molestations and sex offender releases. I initially expected to find that it would be a foregone conclusion that GIS is an logical, ideal, and powerful tool for educating and informing the public in compliance with Megan’s Law requirements. It is. However, what I was not prepared for the amount of legislative and legal restrictions regarding access to and dissemination of offender data in California in contrast to other states. As I originally started to explore the feasibility of creating a generalized local mapping of prior offenders for Sacramento County, my initial investigation entailed finding out what data was available from the county law enforcement agencies and the California Justice Department. My first inquiries appeared promising. Information from the Office of the State Attorney General and Sacramento County Sheriff website indicated I could visit my local Sheriff substation to view the statewide offender data. My visit began with a verification of my Identification to ensure I was not a listed offender. I was given a form to read and sign that indicated “Any person who copies, distributes, discloses, or receives this record or information from it, except as authorized by law, was guilty of a misdemeanor, punishable by imprisonment in the county jail not to exceed six months or by a fine not exceeding $1,000, or both.” My initial anxiety aside, I was able to examine the information available to the public. I encountered a set of detailed information on prior offenders including: name, aliases, zip code of last residence, rap sheet, age, birth-date, height, weight, eye color, hair color, tattoos, and photograph. But what was missing was any useful address information beyond zip code and county. I don’t know about most people, but I really don’t know what the boundaries of my zip code encompass. So I entered my zip code and up popped 90 total offenders – 2 High-Risk and 88 Serious. Then I entered a search fir Sacramento county, resulting in over 2,700 total offenders!!! So I regrouped, thinking I could do analysis and statistics based upon zip code numbers from the state database. After all, the state system allowed searching by zip code, so I expected the state would have data by zip code available. I could hardly have been more wrong. Upon contacting the State Justice Department program manager, I learned that such data was not readily available or accessible. So I regrouped again and continued Internet research. I started finding local, state, and national data related to numbers of offenders on websites like KlassKids.org and CriminalWatch.com, to name a few. I found information on differing state programs for notification and I found a wealth of opinion material related to privacy of prior offenders contrasted to the public’s right to know. From the data and initial analysis, I was not seeing anything immediately apparent to explain the variance in offenders from county to county. Then I noticed that counties with lower percentages of per capita offenders included Marin, Orange, San Mateo, and San Francisco counties. All high cost of living areas. So I retrieved median income data for every county from the 2000 census and made comparison, resulting in the correlation between median income and offender populations noted in this report. Also from the information available I decided to provide a

comparison of the relatively successful Florida system versus a failing

California system and the efforts of some local jurisdictions within

California to overcome a vacuum caused by the lack of a coherent statewide

program. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References Associated Press, Tracking Missing Sex Offenders Could Cost State $20M, San Diego, January 9, 2003 Associated

Press, Money Still

Lacking to Improve California's Megan Law. San Francisco, February 6, 2004. Associated Press, Year later, Megan's database no better, San Francisco, February 6, 2004. California Attorney General. California Sex Offender Information, Violent Crime Information Center, California Attorney General. 2001. (pps. 1-26) California Attorney General. 2002 Report to the California Legislature. California Sex Offender Information. Megan’s Law. Violent Crime Information Center, California Attorney General. 2002. (pps. 1-33) California Attorney General. California Sex Offender Statistics, as of January 20, 2004. California Attorney General, California Dept. if Justice. January 20, 2004. Carter, Madeline M., et al. An

Overview of Sex Offender Community Notification Practices: Policy

Implications and Promising Approaches. November 1997, Center for Sex Offender Management. Digital Map Products . CommunityView™ for Megan’s Law. Online mapping of registered sex offender

information. Digital Map

Products, Costa Mesa, CA. www.digitalmapcentral.com ESRI Inc., ArcIMS Provides Unique Analysis for Sex Offender Locators,

Riverside and Los Angeles Counties, California, Help Their Citizens

Protect Themselves With Megan's Law Web Sites. ESRI Inc., Redlands, CA. www.esri.com Freeman-Longo, Robert E., MRC, LPC. Revisiting

Megan's Law and Sex Offender Registration: Prevention or Problem. 2001. Getis, Arthu, Et al. Geographic Information Science and Crime Analysis. URISA journal, Vol 12, No.2. Spring 2000. Harries, Keith, Ph.D., Mapping Crime: Principle and Practice. National Criminal Justice Reference Service, December 1999. Rose, S. Mariah. Mapping Takes a Bite out of Crime. Business Geographics, June 1998. US Dept. of Justice Publications, Summary

of State Sex Offender Registries, February, 2001. U.S. Dept. of Justice . Summary of State Sex offender Registry Dissemination Procedures, Update 1999. U.S. Dept. of Justice, Office of justice Programs. August 1999, NCJ 177620. (pps. 1-8) Webby, Sean. Public Glare. San Jose Mercury News, April 4, 2004. (pps 1A, 25A). Webby, Sean. Where Sex Offenders Live and Why you Don’t Know; Et al. San Jose Mercury News, December 14, 2003. (pps 1A, 18A-21A). KlaasKids Foundation. Megan’s Law by State, Victims’ Rights by State. February, 2004. State Sex Offender Directories. www.criminalwatch.com California Penal Code Section 290. Sex Offender Registration and Notification. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||