Estimating

Stream Power with GIS: A

Abstract

The GIS method described in this paper may be a cost effective way to screen

out streams that are vulnerable to erosion and prioritize areas to follow up

with rapid geomorphic assessments. Detailed

analysis can then be conducted on the vulnerable stream reaches, followed by the

design of specific land use, flow control and instream

measures. This GIS based approach will

probably save money in the long run for field work and data analysis.

Introduction

The State Water Control Board, Division of Water Quality is charged with ensuring that all land disturbance projects do not cause accelerated erosion in stream channels. Erosion is a natural process but accelerated erosion causes habitat loss, increased water treatment costs, and decreased flood capacity. The Water Board currently lacks a watershed-level method to assess which streams are susceptible to accelerated erosion. This project is an attempt to use GIS to determine erosion susceptibility on a watershed scale.

Background

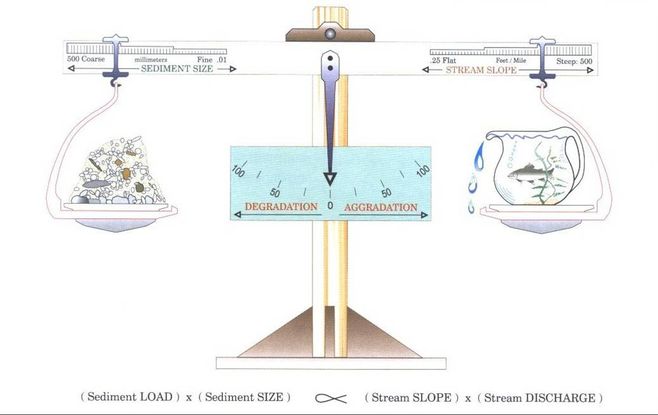

Stable, naturally functioning streams are in balance with sediment supply and

flow such that they do not aggrade or degrade over

time. Figure 1 shows a generalized

relationship indicating stable balance.

Figure 1 – Lane’s Relationship

From Rosgen (1996)

Urban development generally increases the amount of rainfall that ends up as runoff and increases the amount of erosive energy in stream channels (Figure 2).

from OEHHA website

This increase in erosive energy can cause stream channels to incise (bed lowering) and widen, leading to severe accelerated erosion and habitat decline (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3 - Stream channel incision

Figure 4 – Stream channel widening

Perhaps more than any other single parameter, specific stream power has been suggested as a comprehensive descriptor of the overall erosive force of water in stream channels (Bledsoe and Watson 2004, Schroder 1991). Specific stream power is the product of stream slope and the square root of the effective discharge (assumed to be the 2-year recurrence interval storm) and has units of watts per square meter of channel (W/m-2 ). These authors have suggested a boundary for stable/unstable streams of 35 W/m-2

W = s Q0.5

These parameters can be estimated in GIS using readily available data. The GIS method described in this paper may be a cost effective way to screen out streams that are vulnerable to erosion and follow up with rapid geomorphic assessments to check results. Detailed analysis can then be conducted on the vulnerable stream reaches, followed by the design of specific land use, flow control and instream measures.

Methods

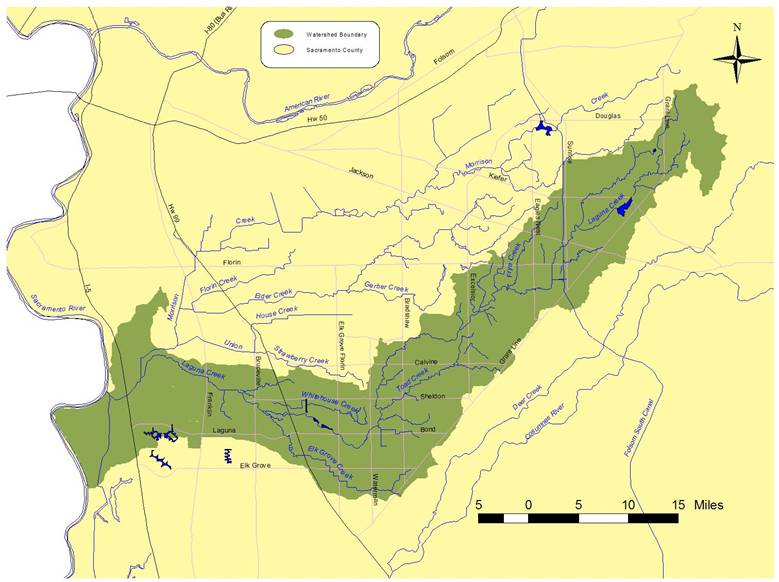

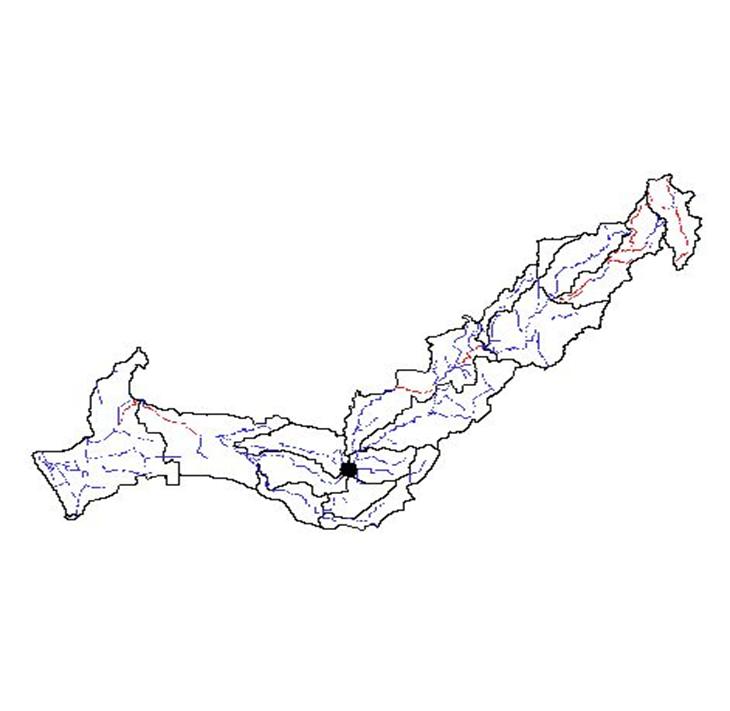

The following methods were used to estimate specific stream power within the

Laguna Creek Watershed in south

Figure 5 – Laguna Creek Watershed

Stream slope

1. Obtained Laguna Creek

watershed shapefile from Laguna Creek Watershed

Council.

2. Obtained the 10 meter DEM for

3. Used Spatial Analyst to calculated slope in percent.

4. Obtained National Hydrography Dataset NHD 1:24,000

data from Water Board GIS holdings.

5. Clipped NHD dataset to represent Laguna Creek Watershed.

6. Calculated stream slope using Zonal Statistics.

Discharge

1. Established the drainage area/discharge

relationship for the project area using all gages in

2. Used Spatial Analyst to fill sinks in the DEM and calculate flow direction

and flow accumulation.

3. Divided flow accumulation grid by 10,000 to get the area draining to each

cell in km2.

4. Used Math Commands to multiply flow accumulation grid by drainage

area/discharge relationship and calculate square root to get the 2-year

discharge to each cell.

Stream Power

1. Multiplied stream slope by discharge to get stream

power.

2. Classified stream segments into 2 categories: 0-35 W/m-2 and >

35 W/m-2

Results

Figure 6 shows the Drainage area Discharge relationship for the 14 gages that

had more than ten years of record.

Figure 6 – Discharge vs.

Drainage Area for

The results of the stream power

analysis indicate that a majority of the Laguna Creek Watershed has specific

stream power values of less than 35 W/m-2 and can therefore be considered relatively

stable (Figure 7).

Figure 7 – Specific Stream Power for Laguna Creek

Analysis

The excellent drainage area/discharge relationship resulted in fairly accurate

flow estimates, larger watersheds may need to look at effects of varying

precipitation as suggested in Finlayson and Montgomery (2003)

Conclusion

This proves to be a promising method-based on readily available information and

may save time and money over a field-based effort. It could probably be done on a large regional

scale.

References

Bledsoe, B.P. and C.C. Watson.

2004. Regional risk analysis of channel

instability. Watershed

Management Conference 2000. American Society of Civil Engineers.

Finlayson, D.P. and

D.R. Montgomery. 2003.

Modeling large-scale fluvial erosion in geographic information

systems. Geomorphology (53), pp. 147-164

Rosgen, D. Applied River Morphology.

1996. Wildland Hydrology,

Schroder, R. 1991. Test of Hack’s slope to bed material

relationship in the southern Eifel Uplands,