| ||

| 2008 Angel

Island Fire: Post Fire Analysis with Photos | ||

|

by

WILLIAM CHAPPELL

American River College, GEOG 350: Data Acquisition in

GIS; Spring 2009 | ||

|

Abstract On Sunday October 12, 2008, a fire started in the early evening and burned across the southern half of Angel Island in San Francisco bay. Firefighters battled it well into the next evening before finally containing the flames. Although the historic buildings on the island were untouched, the south facing half of the island was scorched and scarred. This paper takes up at the point that the fire was extinguished and gives a simple overview of the post fire analysis, by using photos, and shows the rejuvenation of the island's landscape six months after the fire. | ||

|

Introduction  Angel Island is a California State Park and presently is uninhabited except for a few State Park employees. For the most part the terrain is undeveloped and natural. There is a long and varied historical use of the island, from the Miwok Indians, through the Civil War, two World Wars, control of Chinese immigration, and up through the Cold War of the early 1960's. A lot of remnants from these sites are still intact and are visited by thousands of visitors each year. There are also some hike-in campgrounds on the island for those visitors who want an overnight experience, along with a superb view of the lights of San Francisco. But along with campsites comes the element of fire. And along with fire comes a possibility of disaster. It was one of these campers, the Park Service theorizes, that ignited the fire that started up the hill. It raged all through Sunday night and into Monday before being stopped. And although the firefighters were able to contain it before losing any of the historic buildings, the fire blackened the entire southern half of the island. This is where my project begins. Although the fire was out and the firefighters and equipment had gone, the story of this fire did not end there. An assessment of damage and a post fire analysis had to be done. Some recovery actions needed to be acted upon immediately, while others would be assessed and monitored for many weeks, months, and even years to come. I will outline some of the main objectives in doing a post fire analysis along with collecting a series of photographs showing the recovery of the landscape in the months since the burn. Angel Island vegetation is populated with California native trees and shrubs which have adapted themselves to survive fire and regenerate themselves. But, the island is also populated with many non-native invasive species of plants. You will see through the photos that the landscape is coming back and that the fire will ultimately be viewed upon as a benefit to the island's landscape. | ||

|

Background Fire alters the landscape. There is no doubt about that. But what looks like a devastating event in the short term, can be a rejuvenating event in the long term. Fires create immediate damages like dead vegetation, displaced animals, and erosion problems. But fires also create long term benefits to an ecosystem like forest regeneration, seed germination, understory clean out, and many others. In a large fire, the forest service may assess the fire by bringing in a team that can include soil scientists, hydrologists, foresters, botanists and others with a wide range of knowledge and experiences as needed.Univ. of Idaho: "After the Burn" On smaller fires, including the Angel Island fire, conditions are just generally assessed for any emergency conditions, for example public safety due to weakened trees or serious erosion, and then periodically monitored while the burned area makes its own natural recovery. A typical post fire analysis, conducted shortly after the fire is out, will touch on most of the following items, although due to staffing and budget constraints, not all were done on Angel Island:

| ||

|

| ||

|

Methods CAMERA USED: Kodak Z730 Digital Zoom Resolution = 230dpi; Color: sRGB; ISO: 80; Exposure: 1/180 sec.; Aperture: F/4. GPS UNIT USED: Garmin "GPSmap 76S" - 12 channel handheld GPS receiver; Quad Helix antenna; 4 level gray monochrome display. | ||

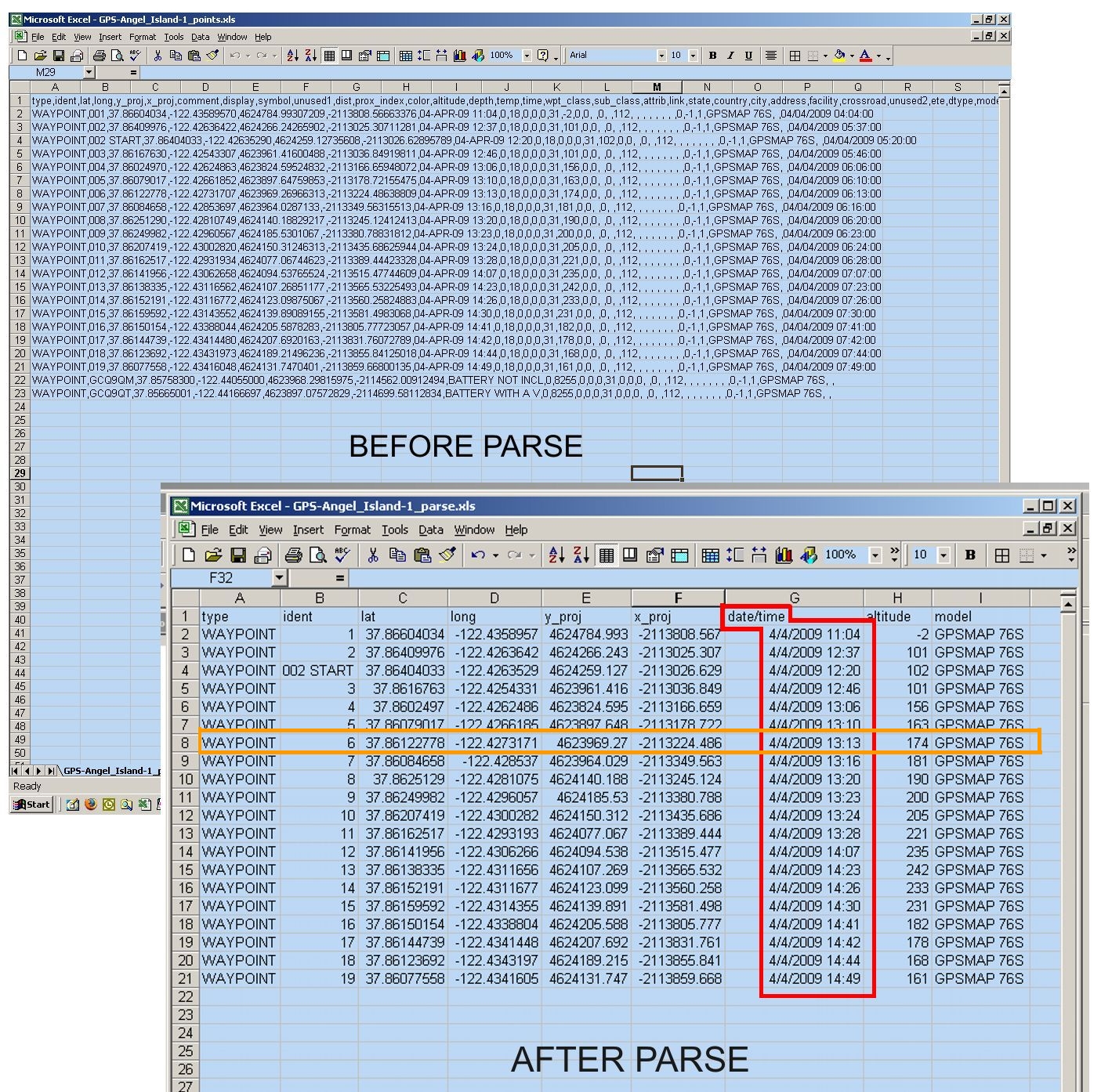

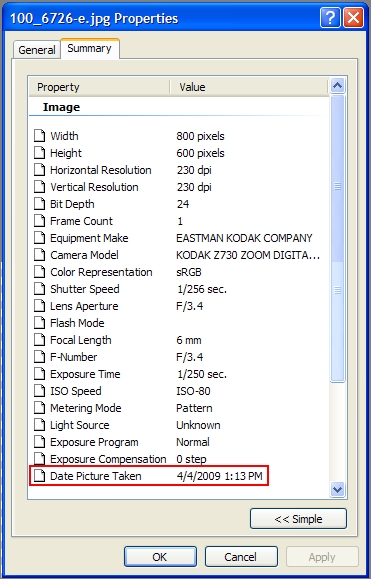

| Data Recording: In the field, I went into the Garmin GPS unit and into the Kodak camera, found the internal clock for each and reset the camera's clock to match (to the same minute) with the Garmin's clock. At each photo position then, I would take my picture, immediately enter a waypoint into the GPS unit, and then enter a picture number into my paper notebook, with a brief description of what the photo was about. I repeated this process as I hiked around the island, documenting the items that I wanted to include in my post fire analysis. Back at home: At home I downloaded the waypoints into DNR Garmin sofware, then exported them out of DNR Garmin as a Microsoft Excel file. In MS Excel, I had to parse the data into columns because the entire data came in "fused" together in column-A. I did this by highlighting column-A, then clicking on "Data" tab / Text to Columns / Delimited / Next / by Comma / Finish. It worked well and I was able to see each waypoint, along with their X,Y,and Z coordinates AND their timestamps.  Click to enlarge Excel Parse of GPS coordinates download The pictures were downloaded through the camera's Kodak software into a folder on my harddrive. There was no way that I could download a list of photos and see all their time stamps in one spreadsheet. But with a bit of patience, I was able to open the list of photos in MS Windows Explorer and display them in "thumbnail" view. By right clicking on the thumbnail, I opened "Properties", clicked on "Summary" tab, opened "Advanced" tab, scrolled to near the bottom to see "date and time picture was taken".

I was very happy to see that the time stamps of many of the pictures matched precisely (same hour & minute) with a waypoint time stamp from the GPS unit. The ones that didn't have a match were pictures taken without a GPS reading. To organize the pictures into a workable form, I printed sheets of thumbnail photos ("index printing") with photo file numbers listed by each one. I could then manually compare photo timestamps with GPS timestamps, thereby matching photos to waypoint I.D. Numbers. | ||

|

Results

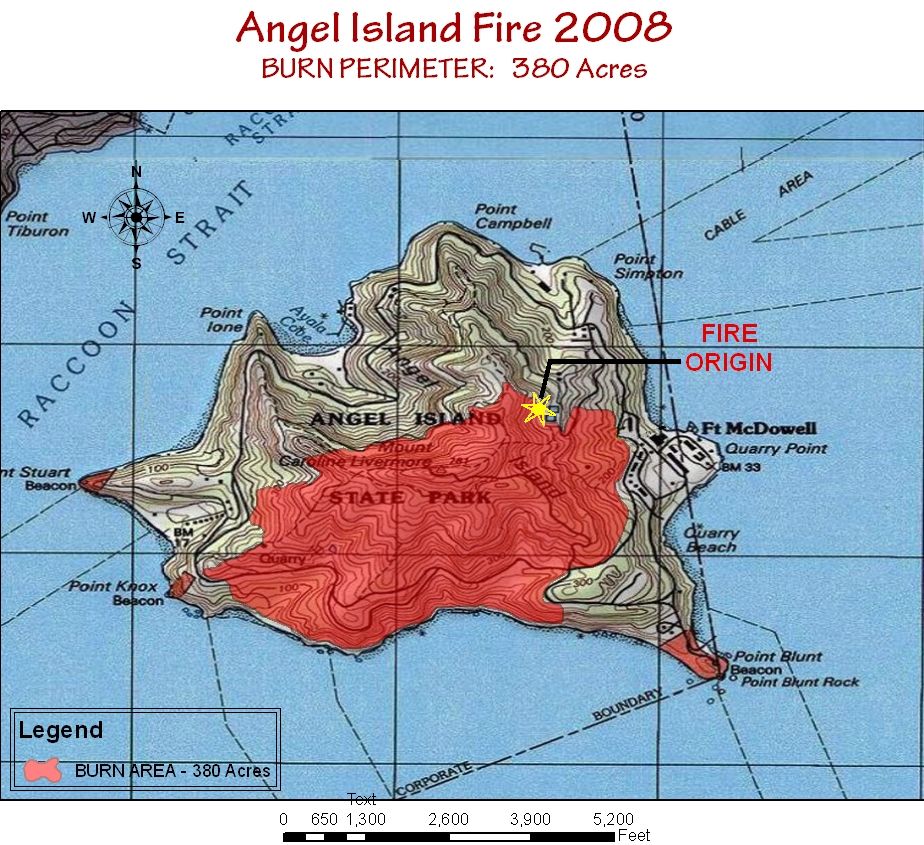

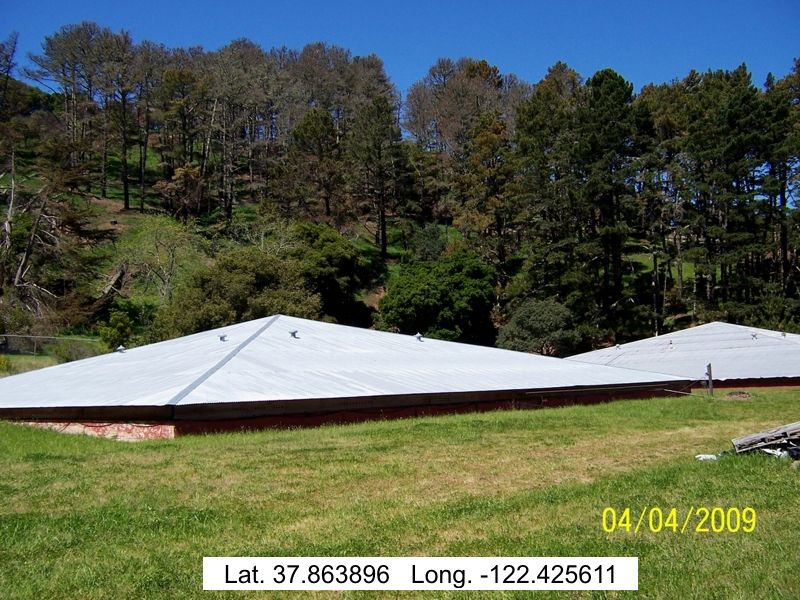

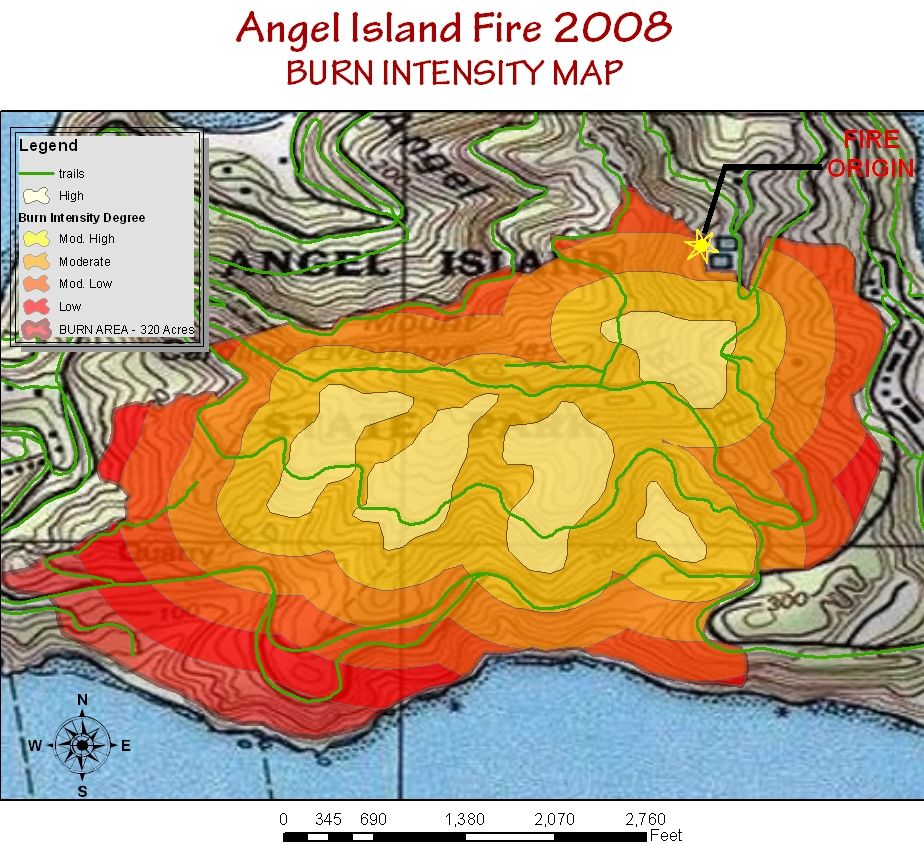

Click to enlarge Click to enlargeNote the "FIRE ORIGIN". It was believed to be human caused and the investigation is currently ongoing, according to Angel Island Ranger Jack Duggan.   The origin of the fire was in proximity to these water storage units. It did not start within a campsite. The flames were first pushed up this hill, aided by easterly winds which were rare for this area of San Francisco bay. You'll notice that only the understory, not the tree crowns, were burned. This indicates a low burn intensity. The fire did not gain its intensity until after it got over the ridge.  Fire did not damage tree due to its thick bark.  These trees will most likely recover because the total canopy (leaves) was not burned.   Note the shurbs are totally burned. If they are a stump sprouting shrub, which these Coyote Bushes are, they will survive come springtime.   This slope had an intense burn. The above ground vegetation here will not likely survive. Anticipate below ground vines and seeds to rejuvenate in the spring and take over the slope.  Click to enlarge Click to enlargeNote: this is only a representative ArcMap overlay of what a burn intensity map might look like. I have fabricated the numbers because a true intensity analysis of the fire is beyond the scope of this project. The following are pictures that exemplify the various degrees of burn intensity as described above.

(Pic #1: Low burn intensity) (Pic #2: Moderate burn intensity) (Pic #3: High burn intensity) High Burn Intensity: Note the dust kicked up by the walker. There is no organic litter in the soil.   These deer were sighted about two months after the fire.  SIX (6) MONTHS AFTER THE FIRE: California Native Species

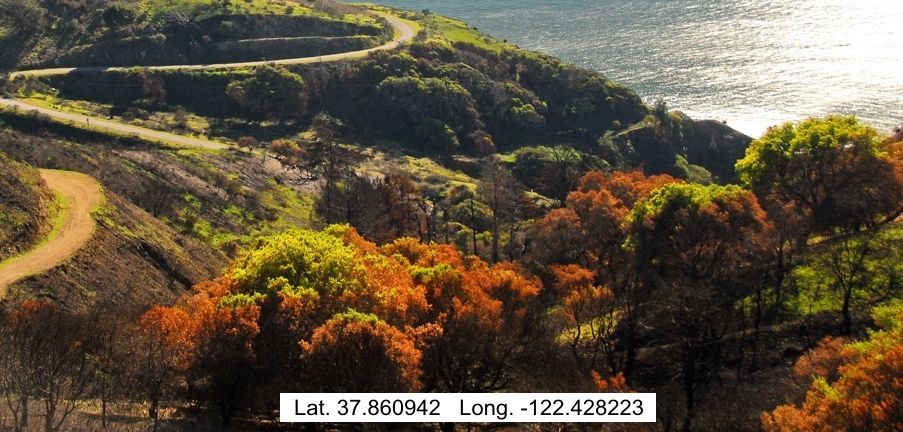

Approximately six months after the fire, the spring rains have brought most all of the burn area back to life. The following are photos documenting some Calfornia native species of vegetation that have adapted their survival to fire. They do this through stump and bud sprouting.

Coyote Bush stump sprouting in spring, six months after the fire.    California Live Oaks have hidden buds under their bark which, if not damaged by the heat of the fire, will sprout out in the spring.    Some natives, if the top is completely burned, will sprout from basal buds at the base of the plant. Non-Native Invasive Species

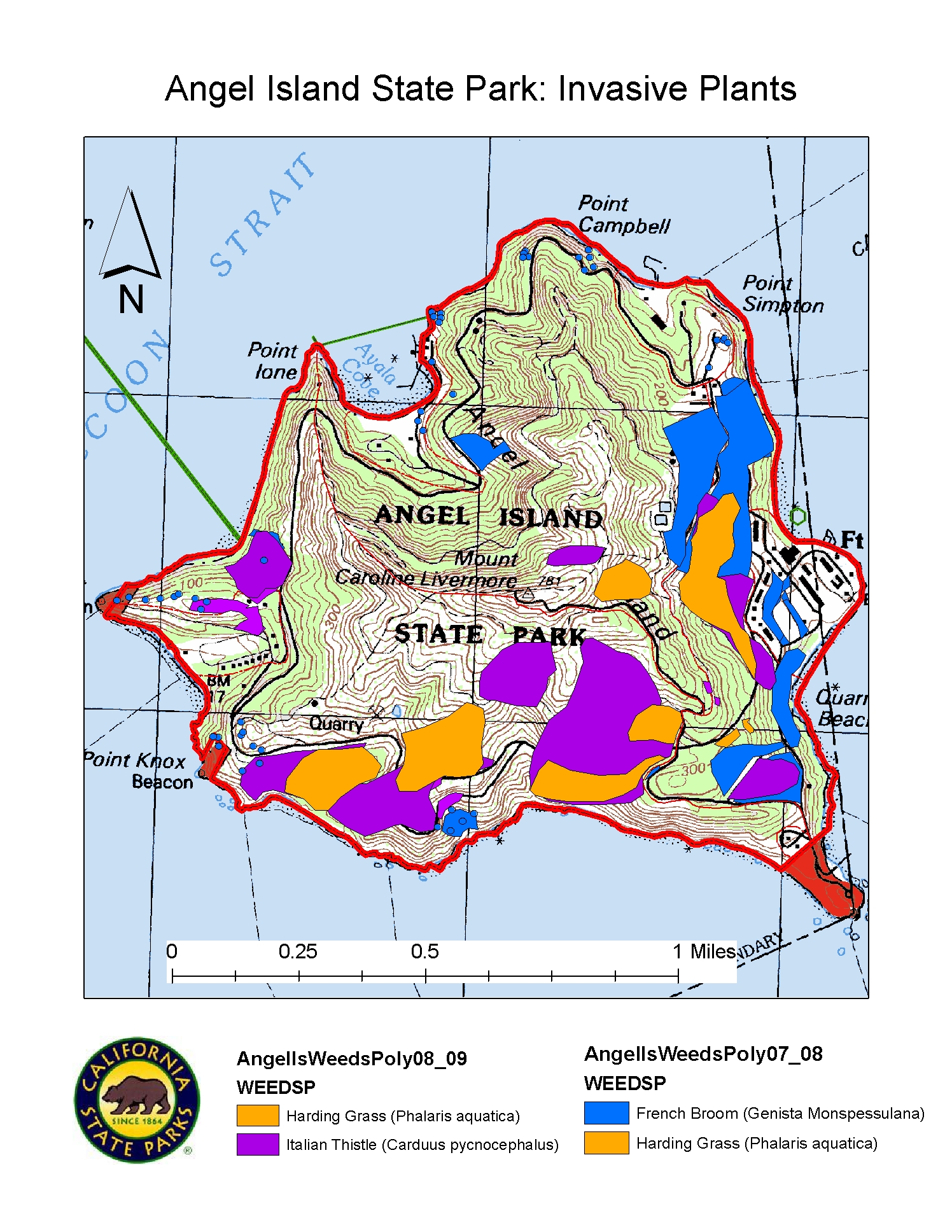

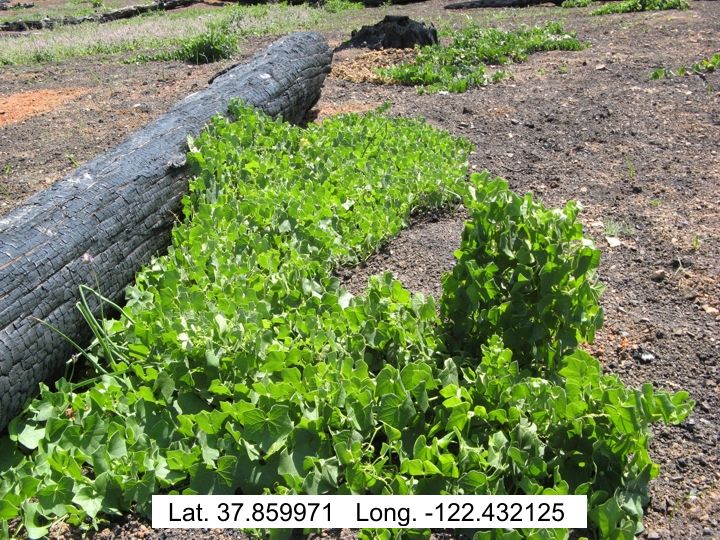

A concern to the California State Parks Department after every fire is the amount of non-native plant vegetation that survives and begins to take over the landscape, quite often out-competing with the native species. The following are examples of non-native plant materials that have taken hold. Click to enlarge Click to enlargeThis map was downloaded from CA State Parks Dept. to show what a typical mapping of non-native plants, as a shapefile in ArcMap, would look like. Actual mapping of current non-native plants, for me to do, was beyond the scope of this project.

(Pic #1: Wild Cucumber Vine) (Pic #2: Wild Cucumber Vine) (Pic #3: Harding Grass) The state parks department is currently trying to eradicate this grass as evidenced by the herbicide kill in the picture.

(Pic #1: Thistle) (Pic #2: Thistle) (Pic #3: Broom)

(Pic #1: Soap Plant) (Pic #2: Soap Plant) (Pic #3: Herbacious Plant) Deer Sightings

Very few animals on Angel Island were thought to have been killed by the fire. Most moved to the other side of the island. There was one reported raccoon that died. The parks department will be doing their annual deer count this summer. It has been estimated that there is a herd of about 60 deer living on the island. I can say that I never saw any deer before the fire, but have seen dozens of them each time I have visited after the fire. This is probably due to the increased visibility and lack of underbrush for them to hide in during the day.

| ||

|

Analysis Overall, I was happy with the way that the project of creating a post fire analysis, by use of photos and waypoints, turned out. Synchronizing the clocks in the camera and the GPS unit worked well. The timestamps matched and after a couple of translations through some other program software, I was able to use the pictures and the data when I returned home. There were, on the other hand, several parts of the project that I had to be creative and wrestle through. The biggest problem was that I should have been doing all the preliminary data collecting and analysis immediately after the fire. But last October, when the fire took place, I had no idea that I'd be doing this project. By March of this year, spring grasses had germinated and made it impossible to see where the burn area and edges were. It was very helpful to have gotten some early-on data from the Marin County Fire Dept. and the Calif. State Parks office. In other parts, for instance the burn intensity analysis, I could only represent what a map overlay might look like, since no analysis was performed. I was forced to create a map with some fabricated data, to be used for demonstration purposes only. I also would make improvements on my data collecting by taking better field notes of pictures taken, corresponding with waypoints taken. Although the timestamps matched, I ended up with lots more pictures than waypoints. It would have been easier to match later at home if I had had a one-to-one photo-to-waypoint numbering system. I also spent a lot of time manually matching camera timestamps to GPS timestamps. For future projects of this type, I would look into using an integrated software that would do this for me. (see "Conclusions" below) To be more scientific in my photo analysis, I should have used a better system to show measurement in my pictures. A ruler and/or tape measure in the pictures would have given a better measurement reference to compare against on any follow-up analysis. I would certainly do this next time. Finally, it is worth making a note of the ongoing controversy regarding the groves of eucalyptus trees, a non-native species of vegetation, on the island. Eucalyptus is well documented for their explosive fire properties, sometimes being called the ďgasoline tree" audubonmagazine.org. Bree Hardcastle, a state parks environmental scientist, pointed out that "the picture would have been much uglier if most of the island's hot-burning eucalyptus trees had not been removed 12 years ago". But surrounding Camp Reynolds on the west side of the island is another grove with historical significance, connected to the Civil War camp. With proper cleanup and regular, on-going maintenance, it is argued that they should stay. In regards to future fires on the island, this is a divisive issue that most likely will continue to be ongoing. | ||

|

Conclusions

Although the fire of Oct. 12, 2008 scorched half the acreage of Angel Island, my overview of a post fire analysis through photos presented above shows that the island's landscape is indeed coming back to life. In fact, the fire was a sort of cleansing prescription, called on to burn off the overgrown slopes and create a chance for the vegetation to rejuvenate itself.The burn area will continue to be monitored and analyzed for years to come. A suggested practice would be to establish a series of set photo points throughout the island where pictures could be periodically taken and compared for qualitative changes. This would help in inventorying damage and help compare conditions and changes over time. I would also recommend the use of an integrated photo system to geo-tag photos. There are a couple on the market that claim to do a good job. Check into GeoSpacial Experts.com with their GPS-Photo Link software and EveryTrail.com to map your GPS documented trips through photos. You can click here to take a fun excursion on a hike up Half Dome in Yosemite. | ||

|

References Barkley, Yvonne C., August, 2006. Idaho Forest, Wildlife and Range Experiment Station, Moscow, Idaho. After the Burn: Assessing and Managing Your Forestland After a Wildfire. Page 28. www.cnr.uidaho.edu/extforest/AftertheBurnFinal.pdf Deneke, Fred, 08/2002. University of Arizona, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. Recovering From Wildfire. cals.arizona.edu/pubs/natresources/az1294.pdf Fire Ecology and Management in Northern Australia. Ecology Section. Effects of fire on plants and animals: Individual level. learnline.cdu.edu.au/units/sbi263/ecology/individual.html McCreary, Doug. U.C. Sierra Research and Extension Center. Homeowners: What to do after a fire. firecenter.berkeley.edu/toolkit/homeowners.html Prado, Mark 04/04/2009. Contra Costa Times. After being ravaged by fire, Angel Island is back in bloom. www.contracostatimes.com/news/ci_12075552 Williams, Ted. 01/2002. Audubon Magazine. Americaís Largest Weed. audubonmagazine.org/incite/incite0201.html | ||

|

Appendices Special thanks to the following people for their help with my project: Kent Julin, Ph.D., Registered Professional Forester, Marin County Fire Dept. Bree Hardcastle, Environmental Scientist, California State Parks, Marin District. Marty Chappell, San Francisco: Helped with taking many of the pictures used in this project. Related Weblinks: Angel Island Association: www.angelisland.org California State Parks, Angel Island: www.parks.ca.gov Angel Island.com: www.angelisland.com Short overview of the history of Angel Island. www.sfgate.com | ||