Title

The Aftermath of Bark Beetle Infestation in the San Bernardino National Forest

Author Information

Cindy Engel

American River College, Geography 350: Data Acquisition in GIS; Fall 2011

Abstract

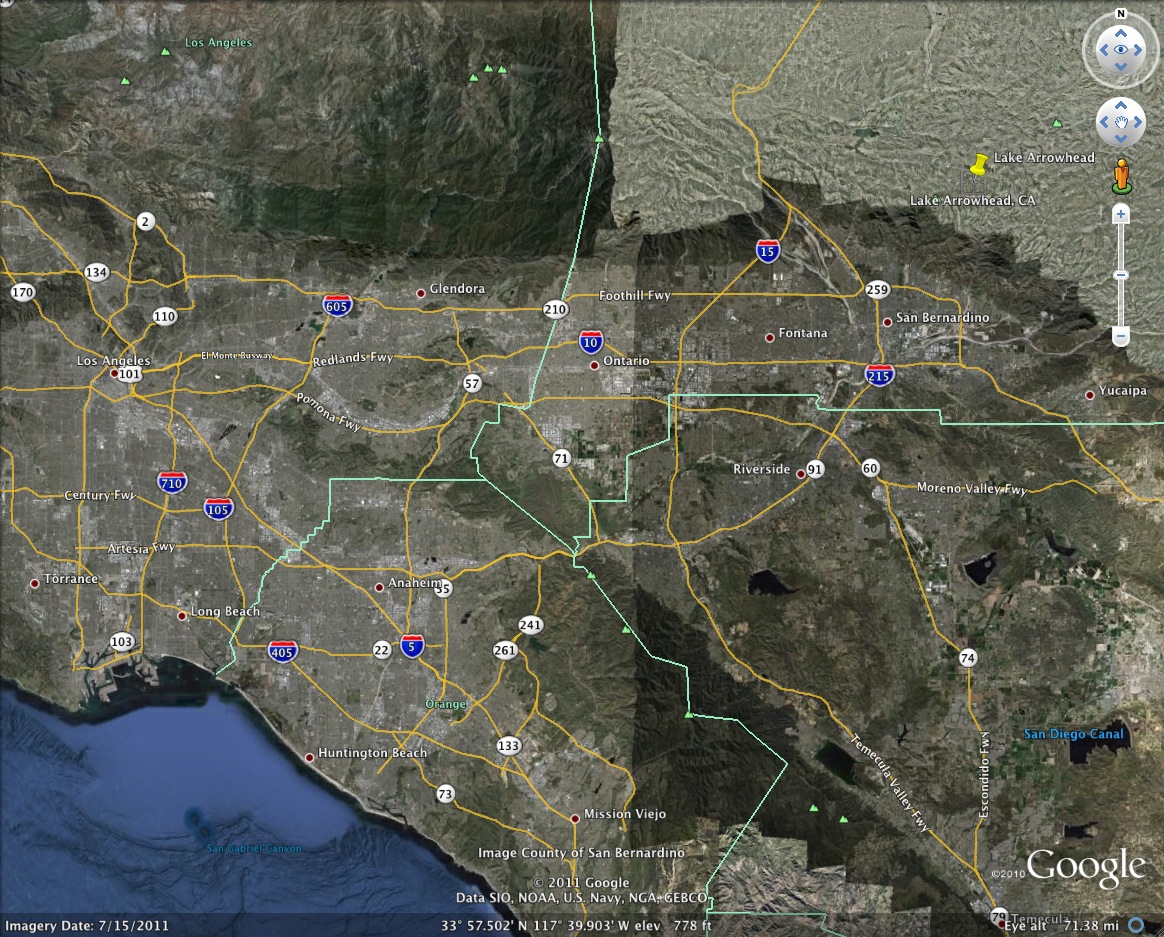

This project looks at the effects of an infestation of bark beetles that devastated a large portion of the San Bernardino National Forest in and around the mountain community of Lake Arrowhead in 2003. Factors such as forest management practices, air pollution and weather cycles combined to make this situation reach epidemic proportions.

Caption for this picture.

Introduction

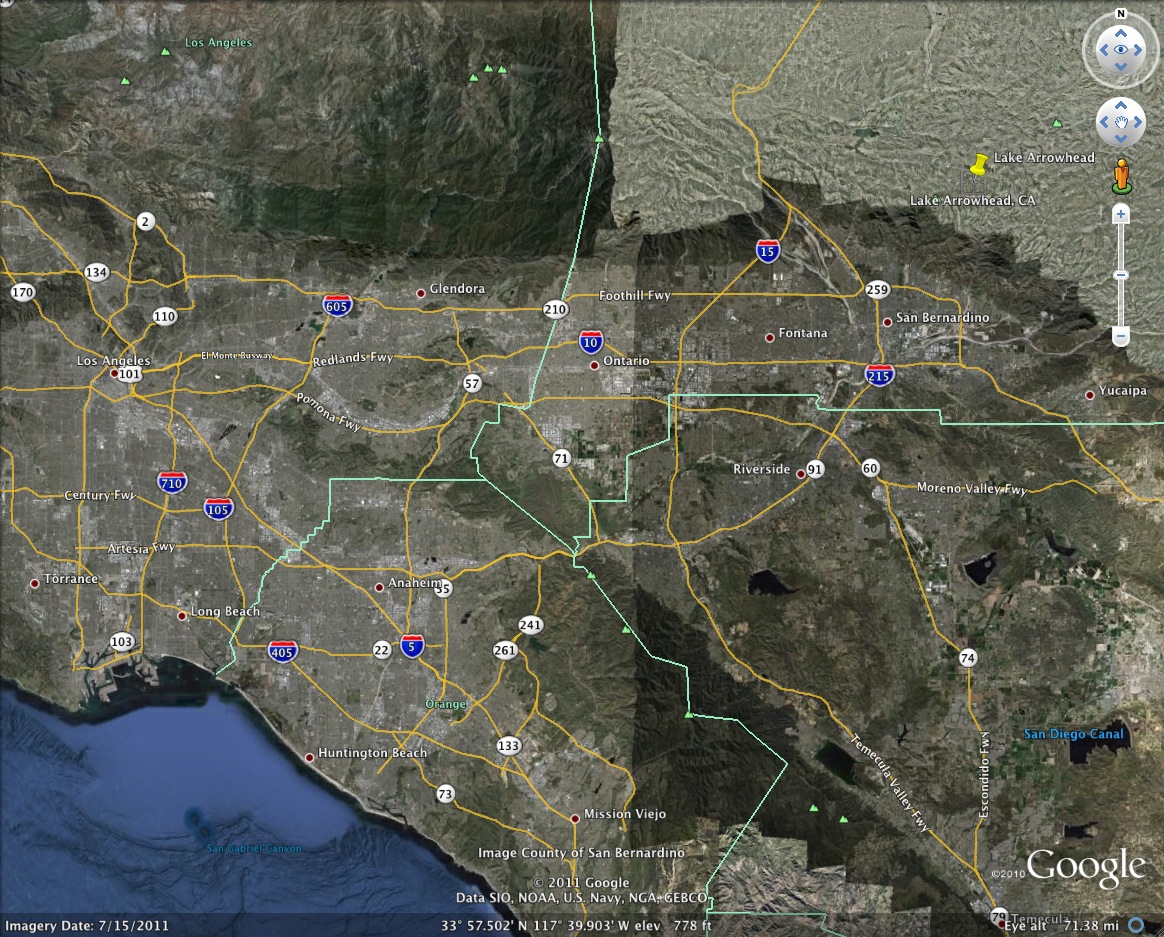

I chose this topic because I lived in Lake Arrowhead for the ten years leading up to the bark beetle infestation. Lake Arrowhead is a beautiful and charming community of about 12,000 residents; a pleasant change of pace from the typical Southern California locale. It is situated at 5181 feet elevation, roughly 10 miles north of San Bernardino, 60 miles east of Los Angeles and 45 miles west of Palm Springs. Specifically, you can find Lake Arrowhead at 34 degrees 14.9000' N and 117 degrees 11.352'W.

The bark beetles began to become a noticeable problem in 1999, as a few pine trees here and there turned brown and died. The problem escalated over the next couple of years, as conditions allowed for a beetle population explosion, and peaked in 2003.

Aerial view of the browning forest on the north shore of Lake Arrowhead, 2002.

A healthy, mature tree, once infested by bark beetles, can become brown and die within a matter of several weeks. Jeffrey, Ponderosa and Coulter Pines are the most susceptible to bark beetles; cedars and oaks are unaffected. The browning of the forest spread at an alarming rate. Soon there was a concerted effort to cut down and remove the dead and diseased trees in an attempt to stop the spread of the bark beetles. For 2 or 3 years, the sound of chainsaws could be heard throughout the daylight hours, seven days a week. Areas that were cleared became small logging assembly yards with thousands of trees stacked up for removal. In all it was estimated that 15 million dead trees were removed from about a half million acres surrounding Lake Arrowhead. The removal effort gained momentum when, on March 7, 2003, then Governor Grey Davis declared a state of emergency because of the imminent fire danger from the extraordinary number of dead, dying and diseased trees. This made U.S. Forest Service and Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) funds available for the removal operations.

Background

Bark beetles are a natural part of the forest community. They colonize on weakened or diseased trees and their population is held in check by the limitations of a healthy ecosystem. Healthy trees can "pitch out" beetles, which means that as a beetle bores into the tree bark, the tree produces a flow of pitch that pushes the beetle back out and prevents injury to living tissue. The three primary factors that can weaken a tree's health and make it more susceptible to invasion by pests are drought stress, air pollution and overcrowded forest conditions. All three of these factors were at play in the San Bernardino National Forest, and contributed greatly to the severity of tree mortality.

Typical views of standing dead pine trees in Lake Arrowhead, 2002.

Drought reduces a tree's pitch production, because adequate hydration is necessary for proper cellular functioning of any organism. When trees are stressed by drought, they are unable to produce enough pitch to expel pests. The female beetles bore through the tree's protective bark and lay their eggs. The emerging larvae eat the living tissue under bark, which further interrupts the flow of pitch carrying nutrients and water to the rest of the tree.

Air pollution, particularly ozone, reduces forest health by causing premature needle loss. This reduces the organism's overall capacity for photosynthesis, thereby compromising the trees' ability to produce food and tissues.

Overcrowded forests have occurred throughout the United States because of fire management practices that prioritize fire suppression. This is an understandable short-term and even medium-term practice when the danger of forest fire is synonymous with the risk of loss of human life and property. The Lake Arrowhead area is no exception to this practice, as it is an upscale resort community and weekend destination for Southern Californians. However, fire suppression prevents smaller, cooler-burning fires from occurring that are a natural part of unmanaged forests. These smaller fires would pass through the forest quickly, clearing out the underbrush and returning nutrients to the soil without getting hot enough to kill mature trees. But over 100 years of successful fire suppression has resulted in dense stands of mature trees that compete for nutrients and moisture, reducing overall forest health.

A good overview of the local issues involved in the Lake Arrowhead bark beetle infestation can be found here.

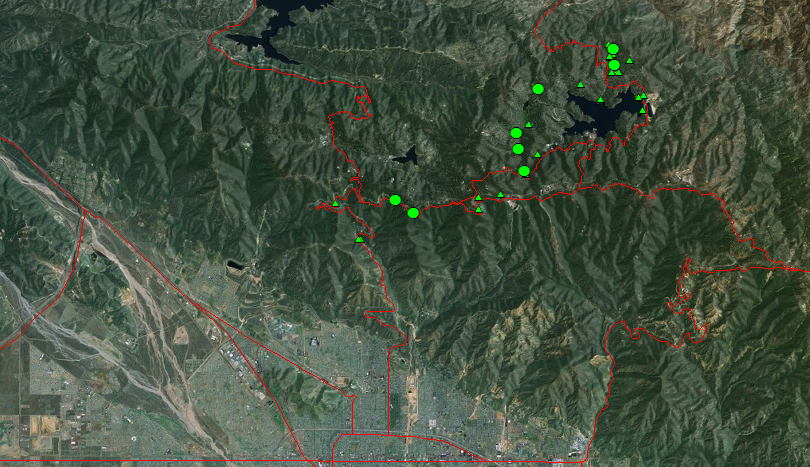

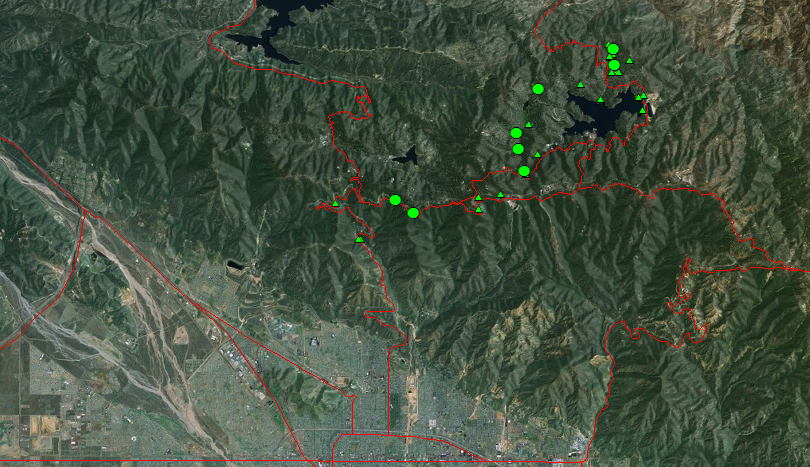

Methods

I conducted a field visit to the Lake Arrowhead area to take digital photographs that document the forest as it looks today –ten years after the bark beetle siege. As I took each photograph, I marked the location with a GPS unit and made notes of the compass direction I was facing so I could accurately account for the content of each photo. I then brought these GPS points into ArcMap, added background satellite imagery and major roads for context, so that the photograph locations could be seen in their overall relationship to the Lake Arrowhead forest community. Here is my resulting image:

GPS locations of digital photos. Large circles represent photos selected for inclusion in this project.

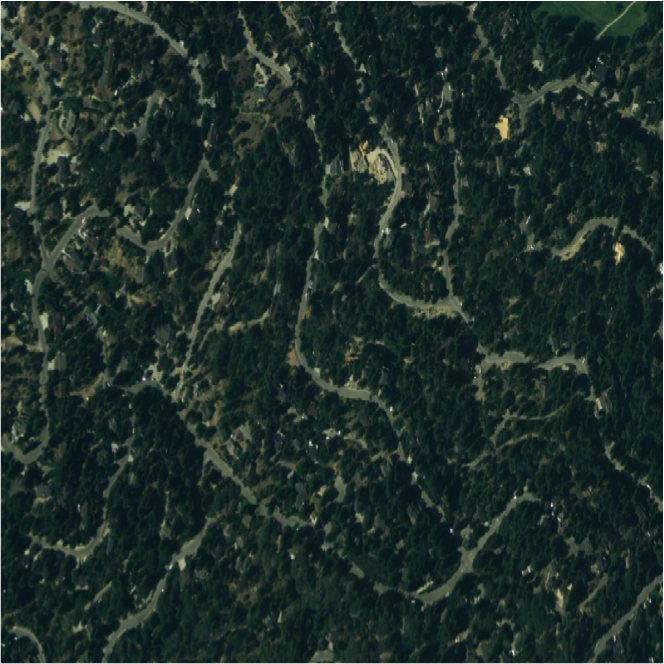

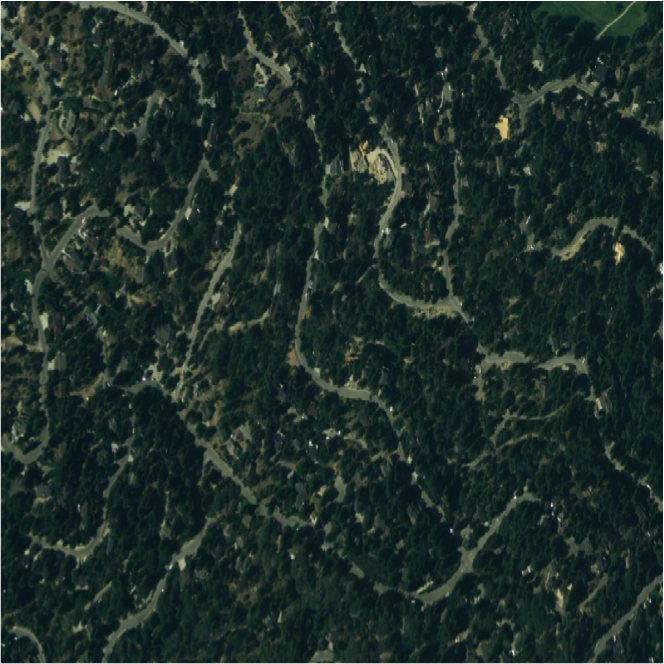

I wanted to make a comparison of what relatively healthy forest looks like in relation to forest that is weakened and dying from the bark beetle attack. Unfortunately, I didn't start my observations before the bark beetles took hold. But I have tried to compile a side-by-side comparison of areas that are at either end of the spectrum of forest health as the Lake Arrowhead area exists today. Following are a series of photo pairs in which I hope this comparison is evident. The first pair of photos are portions of the same aerial photography image from a 2005 NAIP DOQQ image. The two locations are both on the northwestern side of Lake Arrowhead about two miles apart.

The photo on the left shows a neighborhood relatively unaffected by bark beetles. The photo on the right shows a neighborhood suffering moderate bark beetle devastation.

This pair of photos shows a close up view of a stand of trees. Again, the photo on the left shows an area relatively unaffected by bark beetles. Notice the significant diversity in both species and age of trees in a fairly small area. The photo on the right shows a stand of much more uniform consistency that has significant tree mortality.

This final pair of photos shows a fairly healthy area on the left. Notice how the homes are barely visible. The photo to the right shows an area dramatically devastated by bark beetles. Homes all over the mountain suddenly became visible on denuded hillsides.

Results

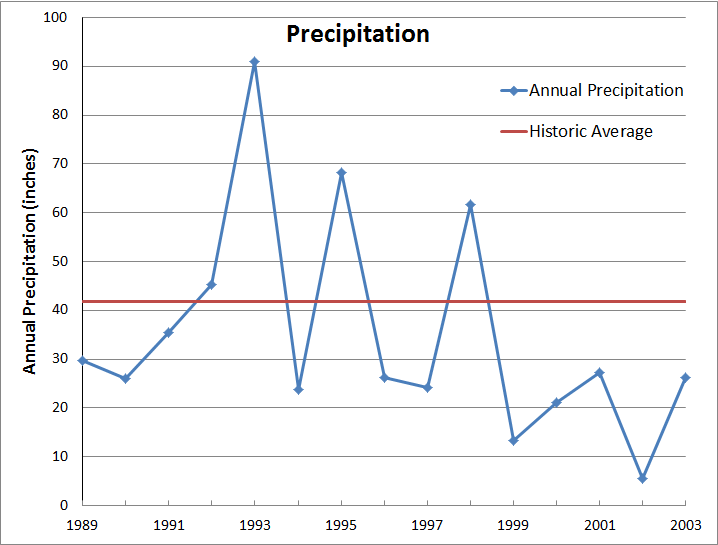

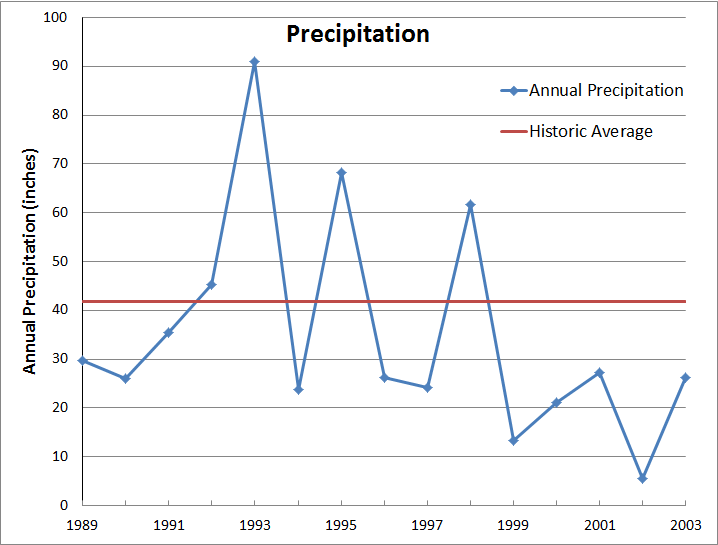

The above photo comparison pairs show the dire effects of a weakened forest that becomes extremely susceptible to an invasion by the harmful bark beetles. As mentioned in the background section, there are several factors that were, are, and continue to be, in play for the ongoing struggle in the San Bernardino National Forest for a healthy ecosystem. Foremost among them is constant threat of drought caused by high temperatures in Southern California and the cyclic pattern of heavy to light rainfall years. Below is a graph showing the amount of precipitation received by Lake Arrowhead over the 15 year period preceding the peak of the bark beetle infestation in comparison to their historic average rainfall amount. Over that 15-year period, the amount of rainfall received in total was at only 83.9% of the normal amount expected. Even more striking is the fact that the five years immediately preceding the bark beetle infestation received in total only 44.9% of what would normally be expected in an average 5-year period. These numbers document that the San Bernardino National Forest was suffering from more than a decade of drought stress, creating a very vulnerable environment for pestilence.

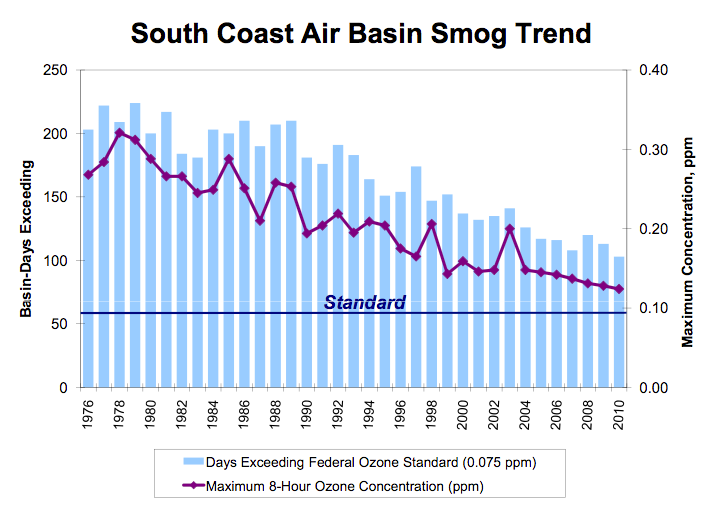

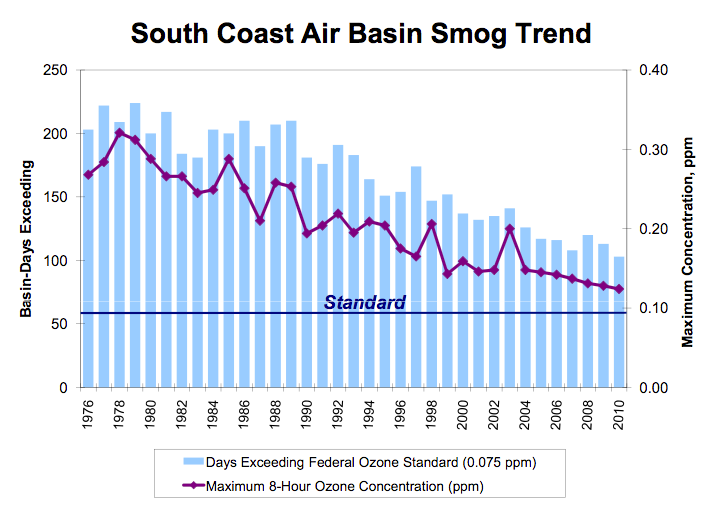

Another significant factor contributing to the overall poor health of the San Bernardino National Forest is its constant, chronic exposure to air pollution in the South Coast Air Basin. Most of the pollution is produced by industry in Los Angeles County and vehicle emissions throughout Southern California. Pollutant levels rise in the basin as the day progresses. Then a typical afternoon on shore breeze carries the whole basin's smog inland until it runs up against the San Bernardino Mountains and spills over the ridge onto the forest surrounding Lake Arrowhead. Of particular harm to plants is ozone, which is produced as a secondary by-product simply from the sunshine causing further chemical reactions in the ambient mixture of air pollution.

Ozone levels for the past 35 years compared to air quality standards; source: South Coast Air Quality Management District.

My final photo comparison follows, and shows the degraded quality of the air basin in the valley below the San Bernardino National Forest as the day progresses. These photos were taken in early November, and clear, cool autumn and winter weather is known to be much clearer than the summer skies in Southern California. You can imagine what the forest puts up with on a real smoggy August afternoon!

This photograph was taken at 9 a.m. on the morning of November 7, 2011. It is a view of the San Bernardino Valley looking south from mountain ridge behind which Lake Arrowhead lies. A slight amount of air pollution can be seen in the distance, southerly and westerly towards Los Angeles and Orange counties.

This photograph is a similar view of the San Bernardino Valley taken at the end of the day, 5:30 p.m. on November 7, 2011. Notice how the smog level and volume has increased over the course of 8 hours.

Analysis

This project does serve to document some of the destructive results of contributing factors that combined to produce a devastating result to the San Bernardino Mountains at the turn of the millennium. Those factors: drought stress, high ozone levels, an overstocked forest community and an opportunistic infestation of bark beetles during prime conditions were reasonably depicted in the images and figures in this paper.

I feel that my efforts at field work to capture the state of the forest in 2011 with digital photography corroborated with GPS position data and presented in a map overall was successful, though at an introductory level. That is not something I could have done at the beginning of the semester, and though rudimentary, I feel this opportunity for data acquisition has given me a strong foundation for refining these skills in the future. The quality of my photos was pretty disappointing, and I was surprised at how many of them really didn't depict what I wanted to capture, and therefore were not used in my project. Photography is a skill and an art, and you must learn to figure out what the image will show without your own perceptions to fill in the blanks. I see how more time must be allotted for data acquisition to really obtain results of the quality necessary.

The other main difficulty I had with this project was difficulty obtaining historical satellite imagery or aerial photography to do a time series study of the forest canopy over a many-decade span. That was my original intention, but I really struggled to find images that could give me a comparison with the 2005 NAIP DOQQ aerial photography that I used incidentally in this project. That was a frustration and I had to change the scope and direction of my project late in the game. But even Google Earth doesn't have color aerial imagery of Lake Arrowhead prior to 2002, so that made me feel a little better! I instead decided to focus on a side-by-side comparison of fairly current photos, rather than a before and after study of the forest.

Conclusion

It seems that any solution lies in appropriate forest management policies. We cannot engineer nature to create more rainfall, and though the air pollution data is actually encouraging in that ozone levels have dropped considerably since the 1970's; today's levels still remain significantly above the standards. For a forest to be healthy despite these environmental stressors, there must be a balance in the quantity and diversity of species that can be supported by the ecosystem in equilibrium. The big opportunity lies in people figuring out how to live in harmony with nature.

References

"About the Forest"; United States Department of Agriculture; Forest Service; San Bernardino National Forest. http:/www.fs.usda.gov/detail/sbnf/about-forest/?cid=fsbdev7_007781.

"Bark Beetles of the Southern California Forests"; http://www.co.san-bernardino.ca.us/museum/barkbeetle/barkbeetle.htm.

"Fire Safety Information to Keep Our Forests Healthy and Your Property Safe"; Mountain Area Safety Taskforce (MAST), 2007. http://www.sbcounty.gov/calmast/bark_beetle_emg.asp.

"Lake Level Analysis: Lake Arrowhead, California"; draft report by Bookman-Edmonston, a Division of GEI Consultants, Inc.; submitted to the Lake Arrowhead Community Services District; June 22, 2004.

South Coast Air Quality Management District web page. http://www.aqmd.gov/smog/o3trend.html.