Picture 5. DWR rotary screw trap located in the Toe Drain of the Yolo Bypass

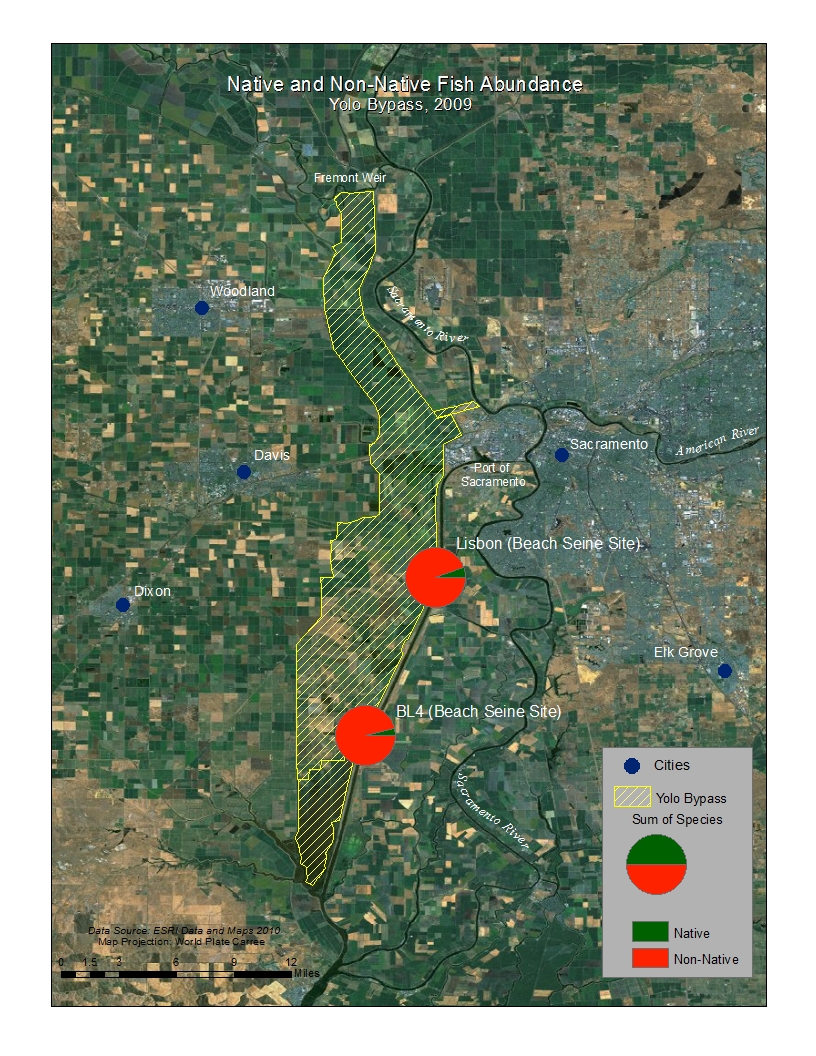

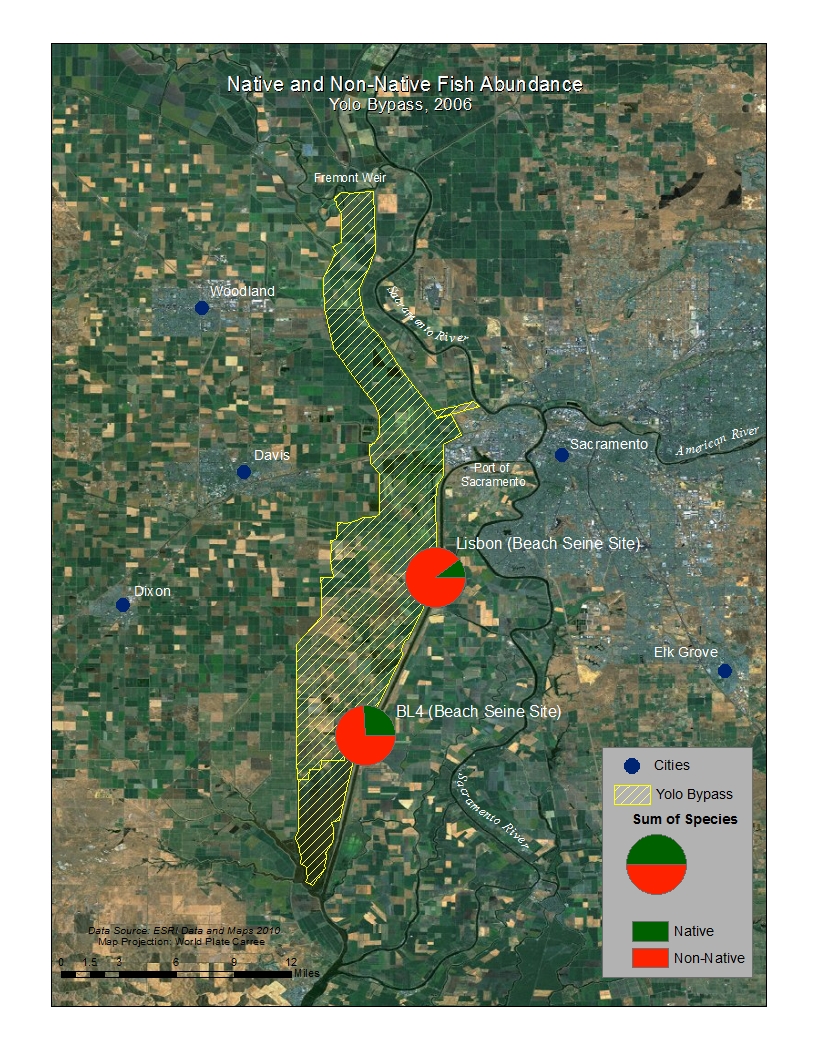

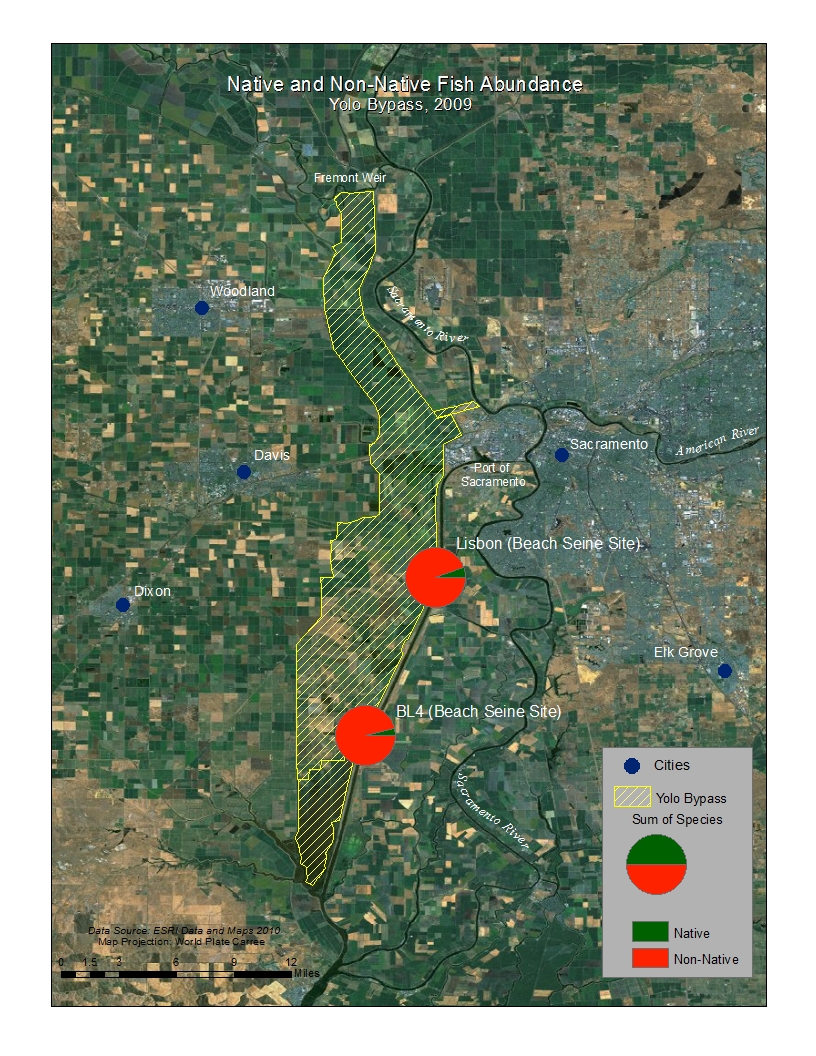

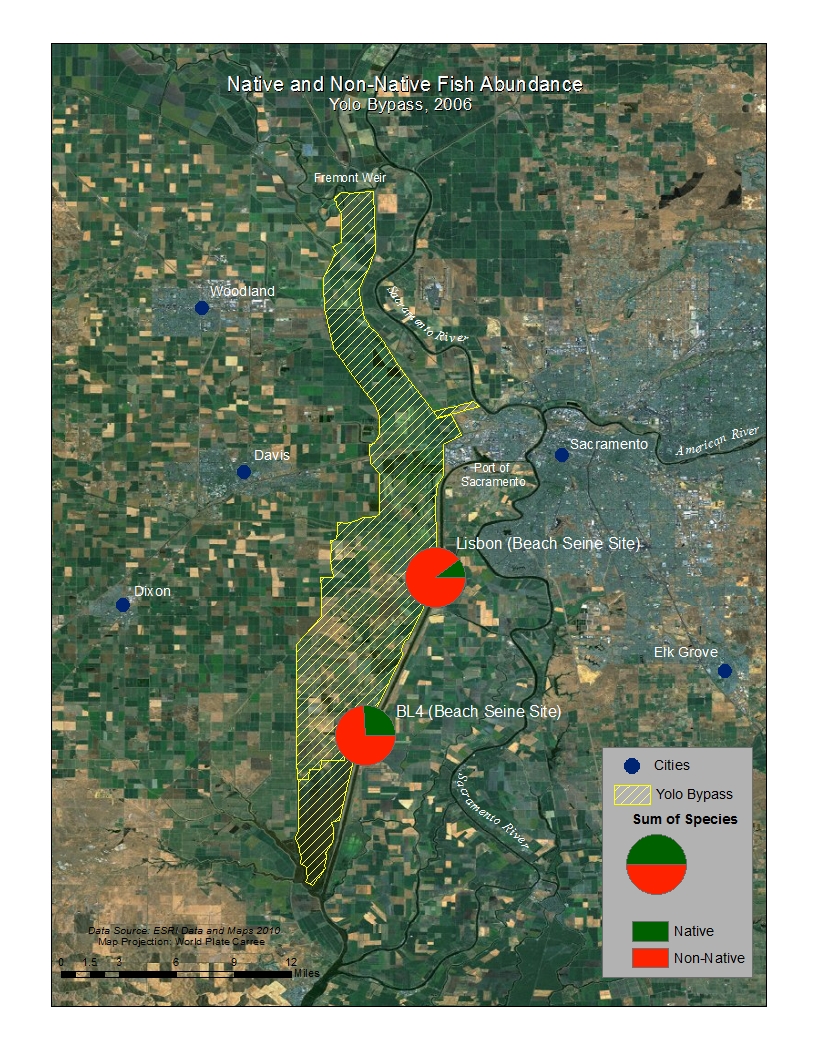

Figure 3. 2006 (Wet Year) vs. 2009 (Dry Year) - Native and Non-Native Fish Abundance in the Yolo Bypass at Lisbon and BL4 Beach Seine Sites

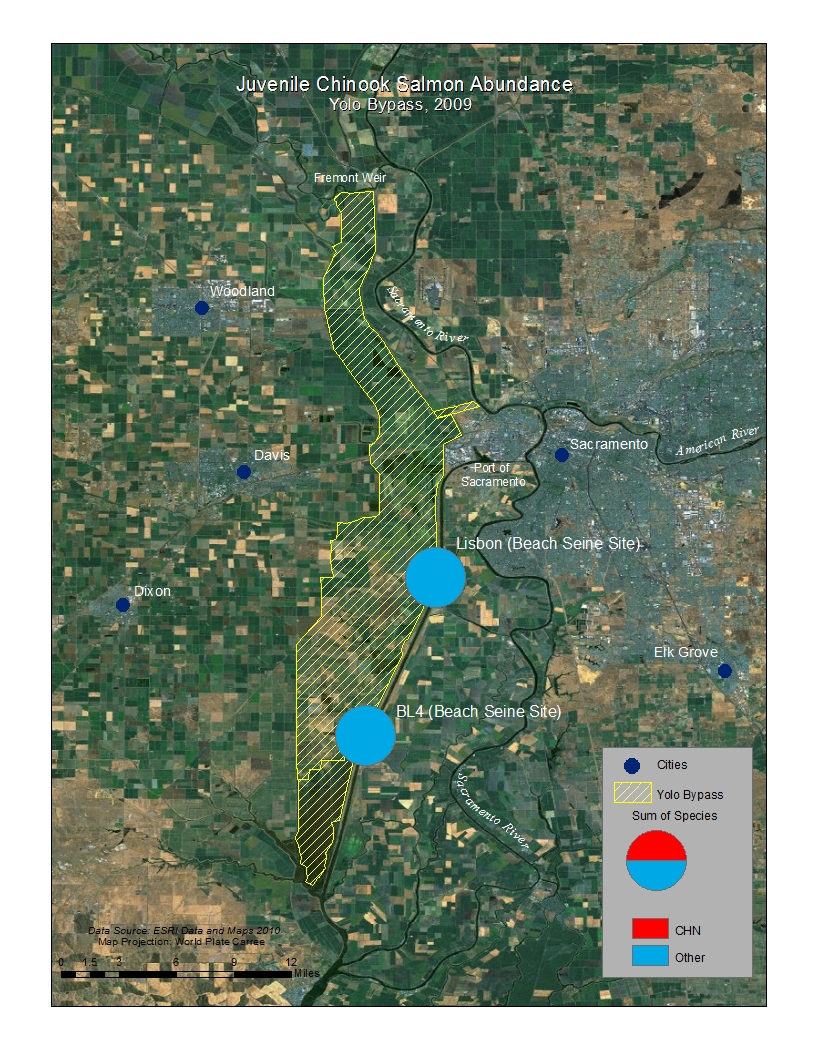

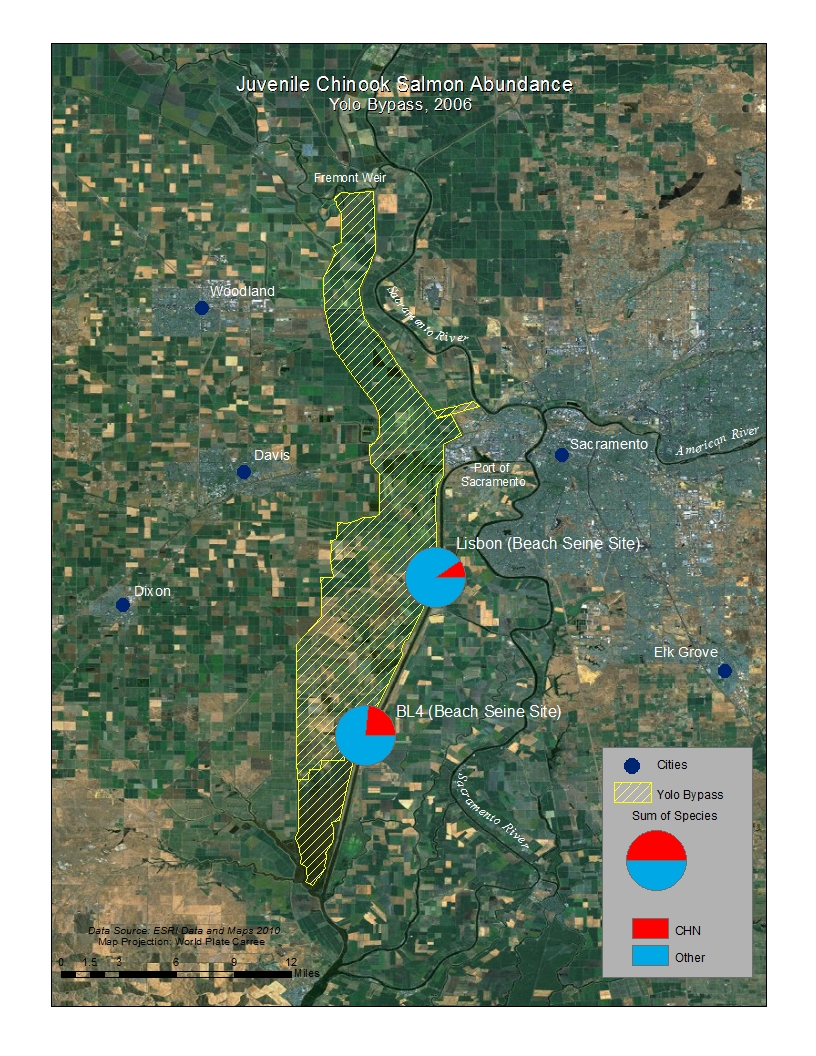

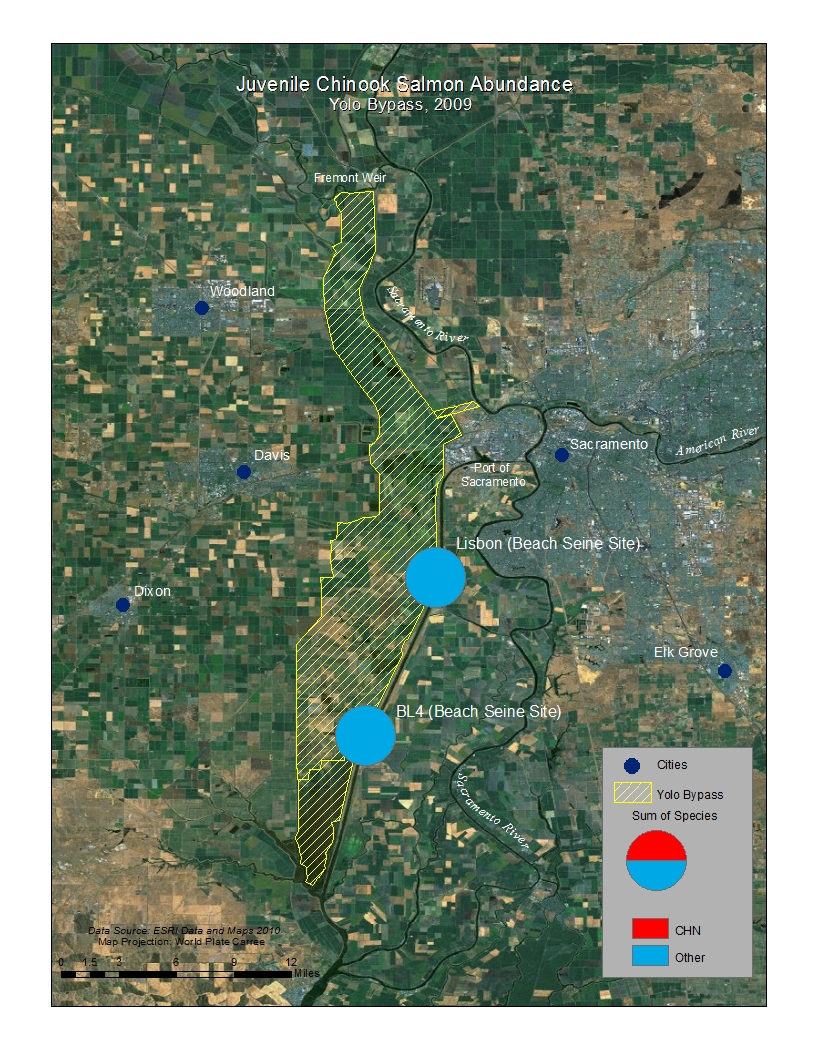

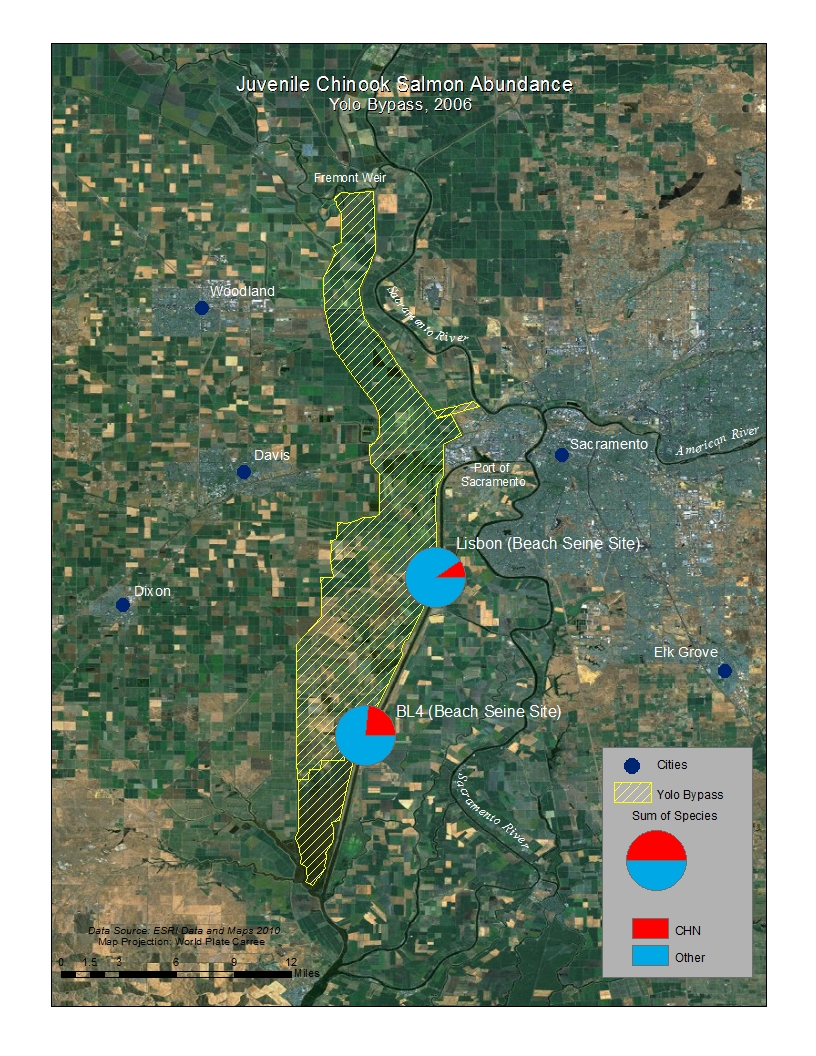

Figure 4. 2006 (Wet Year) vs. 2009 (Dry Year) - Juvenile Chinook Salmon Abundance in the Yolo Bypass at Lisbon and BL4 Beach Seine Sites

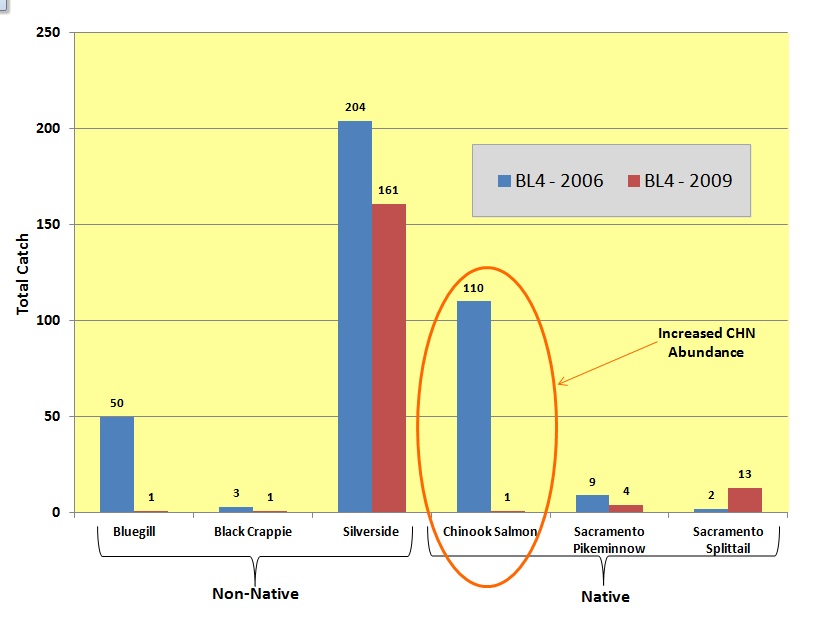

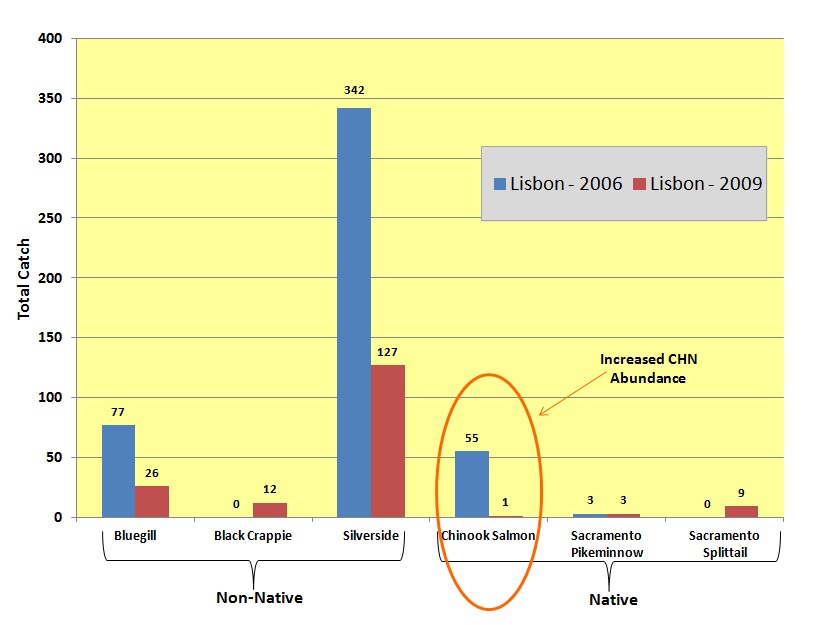

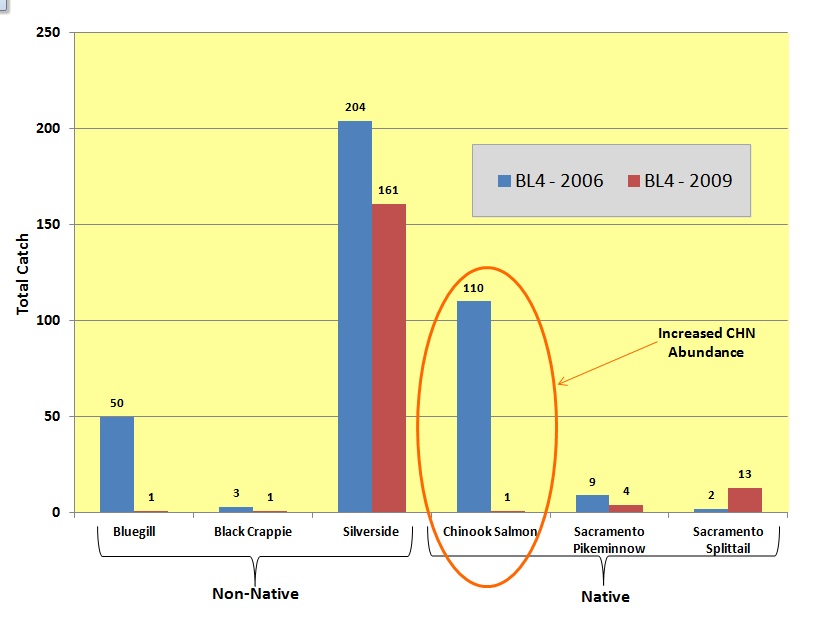

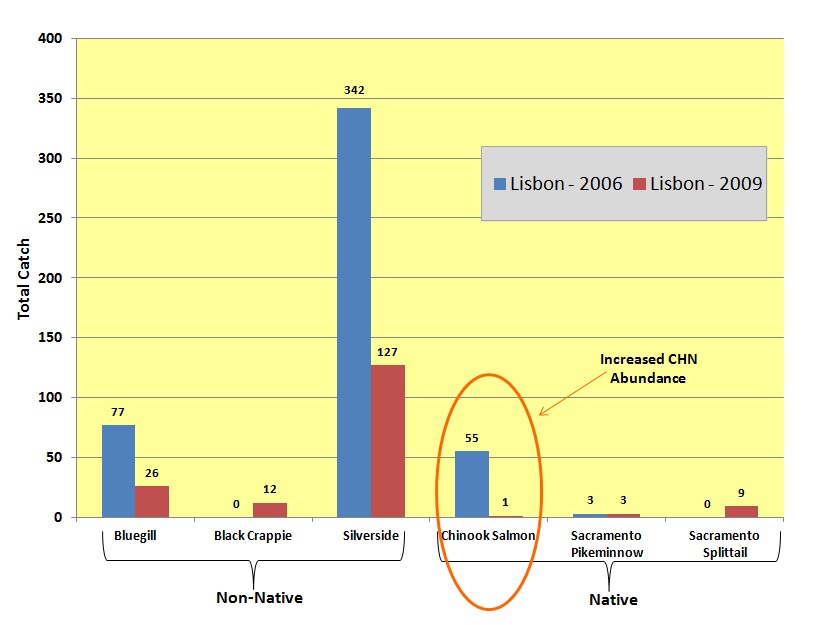

Figure 5. 2006 and 2009 Beach Seine Total Annual Catch of Three Prominent Native and Non-Native Fishes in the Yolo Bypass

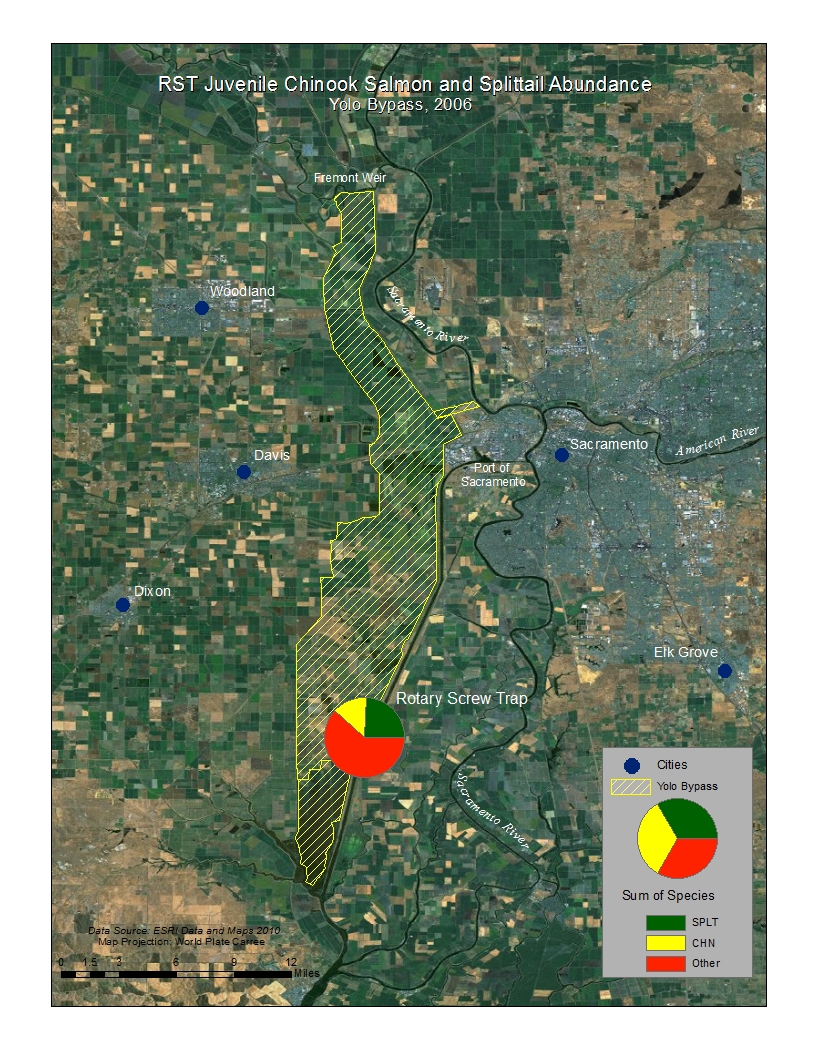

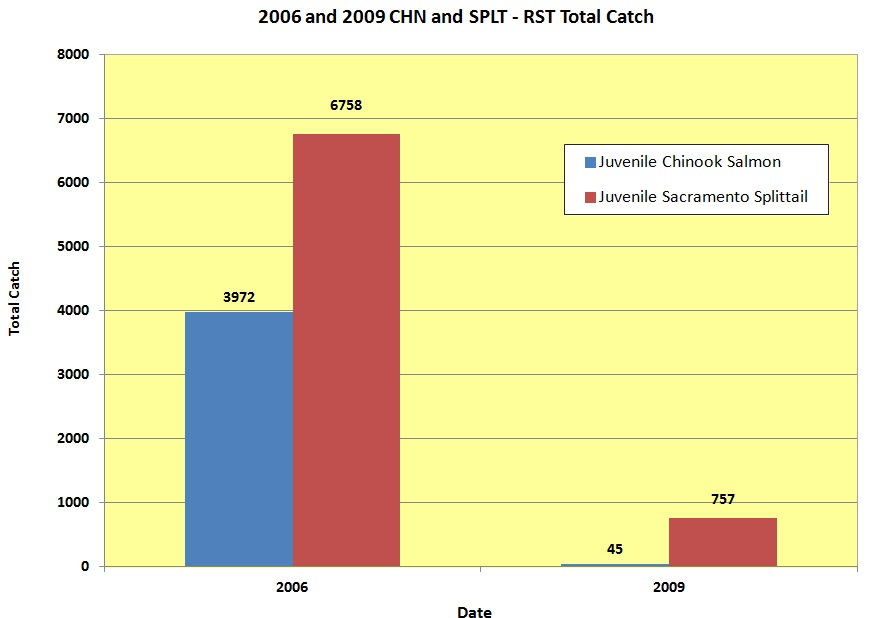

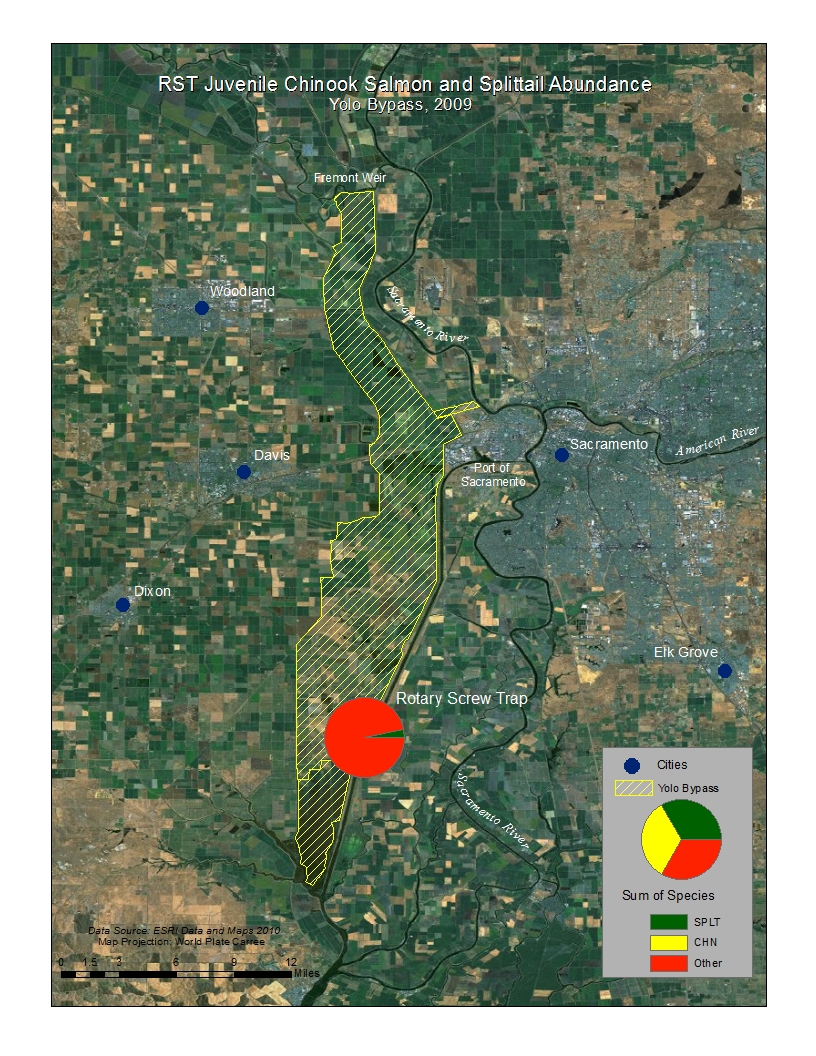

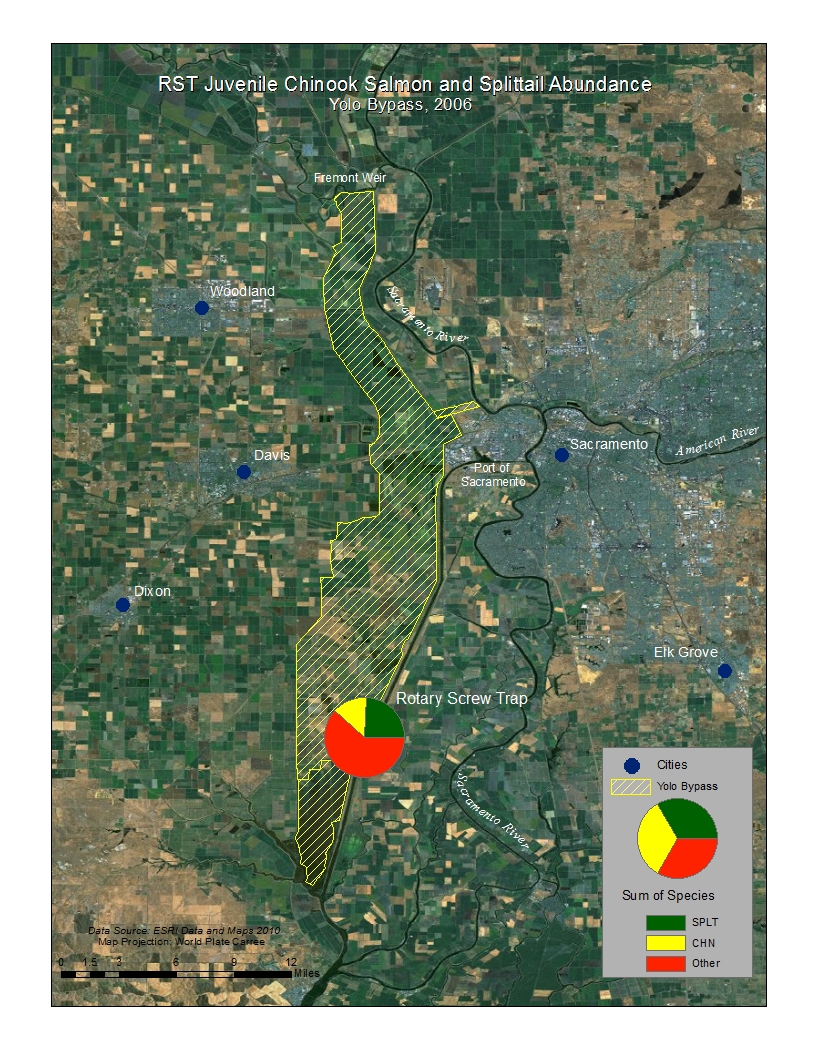

The total catch of juvenile Chinook salmon and Sacramento splittail in the RST in 2006 and 2009 was significantly different (Figure 6). In 2006 total catch of Chinook salmon was 3,972 and 6,758 Sacramento

splittail were caught, which was 38% of the total fish catch for the RST that year. In 2009 total catch of Chinook salmon was 45 and 757 splittail were caught, which was 3% of the total fish catch

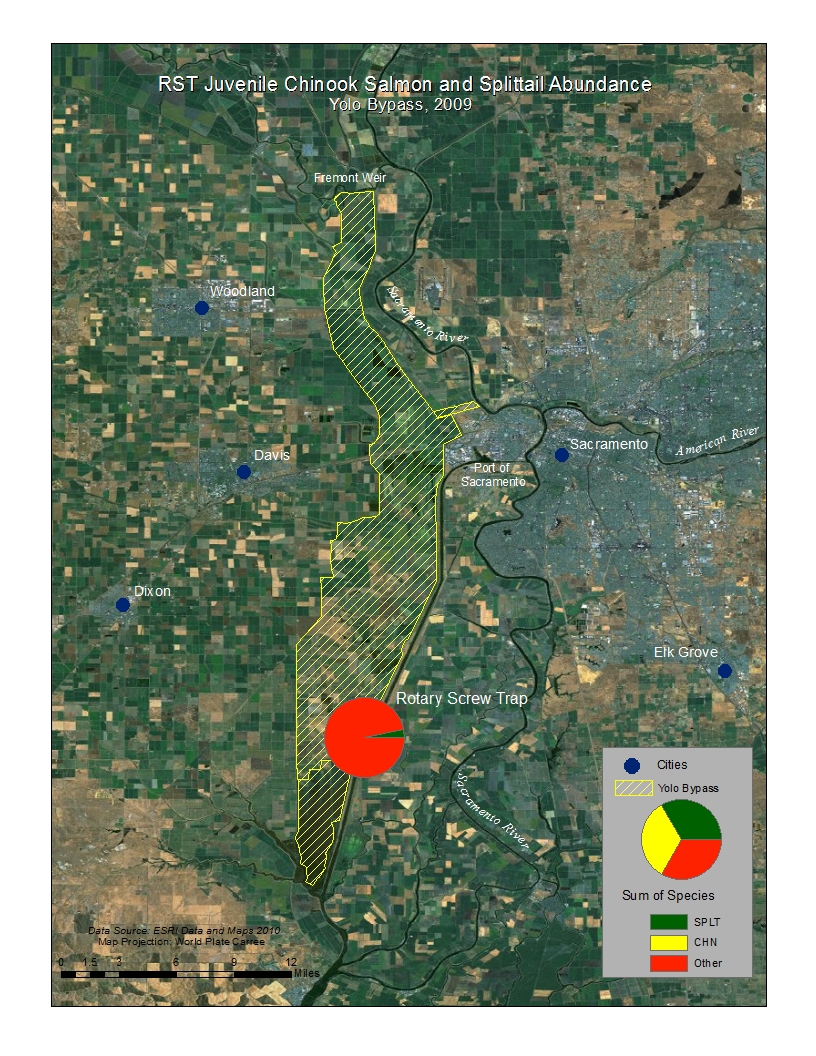

that year (Figure 7).

Figure 6. 2006 (Wet Year) vs. 2009 (Dry Year) - Juvenile Chinook Salmon and Sacramento Splittail Abundance at Yolo Bypass Rotary Screw Trap

Figure 7. RST - Juvenile Chinook salmon and Sacramento splittail total catch 2006 and 2009

Analysis

The use of both the DWR beach seine and RST data effectively showed changes in the fish assemblage in the Yolo Bypass during wet and dry years. It

became important to realize that there are key native fish species that utilize seasonal floodplain habitat. The data revealed that the Yolo

Bypass is dominated by non-native fish species much like the rest of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, but seasonal inundations of the Bypass

resulted in the beneficial spawning of the native Sacramento splittail and rearing of juvenile Chinook salmon. It became essential to also include

the RST data in my analysis of native and non-native fish abundance in the Yolo Bypass, because it is a far more efficient sampling method

than using two biweekly beach seine site transects in the Toe Drain.

Conclusion

The Yolo Bypass provides vital habitat and a sanctuary for a declining native fishery in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. It's in the best interest of California

to continue the research and monitoring in a seasonal floodplain habitat. The continued funding of IEP and the effort by DWR to collect annual data

on fish and food-web dynamics have already exposed many of the benefits to floodplain preservation. I hope that the Yolo Bypass can be used as

an example of future efforts to develop restoration efforts throughout the Central Valley to protect native fishes.

References

Feyrer, F, T. Sommer, and W. Harrell. 2006. Importance of flood dynamics versus intrinsic physical habitat in structuring fish communities: evidence from two adjacent

engineered floodplains on the Sacramento River, California. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 26:408-417.

Sommer, T., R. Baxter, and F. Feyrer. 2007. Splittail revisited: how recent population trends and restoration activities led to the "delisting" of this native minnow.

Pages 25-38 in M.J. Brouder and J.A. Scheuer, editors. Status, distribution, and conservation of freshwater fishes of western North America. American Fisheries Society Symposium 53. Bethesda, Maryland.

Sommer, T. R., W. C. Harrell, M. Nobriga, R. Brown, P.B. Moyle, W. J. Kimmerer and L. Schemel. 2001. California's Yolo Bypass: evidence that flood control can be compatible with fish, wetlands, wildlife

and agriculture.California's Yolo Bypass: evidence that flood control can be compatible with fish, wetlands, wildlife

and agriculture. Fisheries 26(8):6-16.

Sommer, T. R., M. L. Nobriga, W. C. Harrell, W. Batham, and W. J. Kimmerer. 2001. Floodplain rearing of juvenile chinook salmon: evidence of enhanced growth and survival. Canadian Journal of Fisheries

and Aquatic Sciences 58(2):325-333

Sommer, T.R., W.C. Harrell, M.L. Nobriga and R. Kurth. 2003. Floodplain as habitat for native fish: Lessons from California's Yolo Bypass. Pages 81-87 in P.M. Faber, editor. California riparian systems:

Processes and floodplain management, ecology, and restoration. 2001 Riparian Habitat and Floodplains Conference Proceedings, Riparian Habitat Joint Venture, Sacramento, California