Title

Knossos: Does Size Matter?

Measuring Importance in the Late Bronze Age Aegean Through the

Study of Iconographical and Architectural Features with the aid of GIS

Author

Franco Fortuna

American River College, Geography 350: Data Acquisition in GIS; Spring 2012

Contact Information: fwfortuna@gmail.com

Abstract

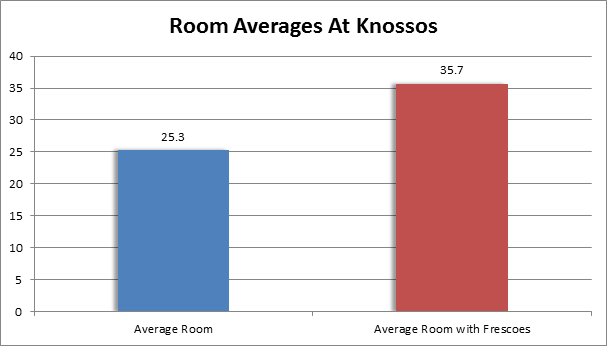

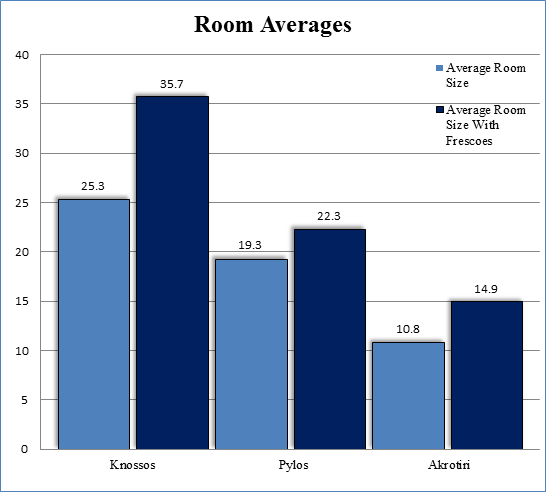

Many times, the size of an object or space is influenced by the significance that is imbued upon it, denoting the axiom “Bigger is Better”. Yet with regard to the construction of rooms in Late Bronze Age Aegean palatial sites, does size denote importance? Several key indications of importance are examined at Knossos to answer this question. The presence of frescoes is considered the chief criteria in locating such rooms, while architectural features are used as secondary support to enhance this assessment. Special attention is given to the particular details of how iconography and architecture define importance at Knossos. Using this criterion, the rooms at Knossos were measured to determine an average size which is then compared to the average size of rooms with frescoes and architectural features. Using ArcMap, the rooms as Knossos were digitized for the first time and thematic and choropleth maps were created to visually demonstrate the outcome of this data collection. The analysis of the data leads to the conclusion that the size of rooms with wall paintings is greater than the average room at Knossos, suggesting a relationship between size and importance.

Introduction

The origins of this project began in 2009 while working on my MA in archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology at the University College London, and would ultimately become the subject of my dissertation. While musing over the significance of size in built space, I began to wonder if size imparts a meaning of its own, suggesting that the larger something is, the more important it must be? Certainly, the archaeological record is replete with these types of megalithic examples, from the Mayan temples, deeply ensconced within the verdant jungles of Central America to the imposing stone facades of the Pyramids at Giza in Egypt. Rising up like an axis mundi, these structures may have been inspired by man’s attempt to connect with the heavens. From ancient times down through the present, this idiom is passed on from the stone parapets and domes of great cathedrals to the steel, spired skylines of modern cities and monuments. While the current perceptions of space and architecture should not be used to understand ancient buildings, there is nevertheless a nagging urge to see if similar principles governed the usage of space in the past.

The typical floor plan of the traditional Western home allots a generous portion of space to both the public and private areas of the home. Master bedrooms are given the most space over all other sleeping areas, while areas where guests are entertained are assigned ample room as well. These places are often bedecked with expensive items, a reminder to occupants and visitors alike of the status and wealth one has accumulated. However, some rooms such as lavatories could be considered as equally important yet appointed much less space. It was in this vein of reflection that I sought to discover whether Late Bronze Age Aegean rooms shared a similar relationship to this model.

Importance, largely a qualitative assessment, is expressed in rooms by the objects which are chosen to occupy that space, creating an indirect way of measuring quantifiable data. Instead of priceless vases, paintings and expensive electronics which adorn the rooms of today, frescoes, architecture and building materials would take the place as their Aegean counterparts.

Wall painting in the Late Bronze Age Aegean survives as the one of the last pictorial vestiges of a bygone civilization, whose insights are otherwise typically confined to rubble walls and sherds of broken pottery. These murals, expertly crafted and costly to produce, were situated in areas where rulers once sat and rituals performed. However, due to the definitive lack of pieces to study and the fragmentary nature of those that did survive, the meaning and symbolism of these frescoes is difficult to discern. Therefore, it is essential to augment the available material with additional features that may attest to the significance of these rooms.

Able to fare the rigors of time somewhat better, architectural features fill in the details where frescoes left off. While these two subjects may at first glance seem unharmonious, in fact they work to complement one another in Late Bronze Age Aegean sites, often uniting the vivid murals with their physical surroundings. It becomes important to consider the various aspects of architecture as integral to completing an analysis of rooms of importance. The spatial layout of the rooms, the construction material used, as well as the levels of public and private space they are afforded need to be considered. Once these various elements are combined it becomes possible to ascertain the level of importance a constructed space may have had.

While much attention has been drawn to the study of particular elements in these rooms of importance—fresco painting technique, room reconstruction, placement of architectural features—less focus has centered on a comparative study of these rooms. It is true that much information can be gleaned from the study of each individual room in of itself, but there is also much to be gained from looking at these rooms of importance from a wider perspective. Using a synchronic approach, the focus of this study seeks to compare those spaces defined as rooms of importance at Knossos to the average room at each site—those characterized by a lack of highly valued features—to gauge what, if any, correlation may exist between room dimensions and high valued features.

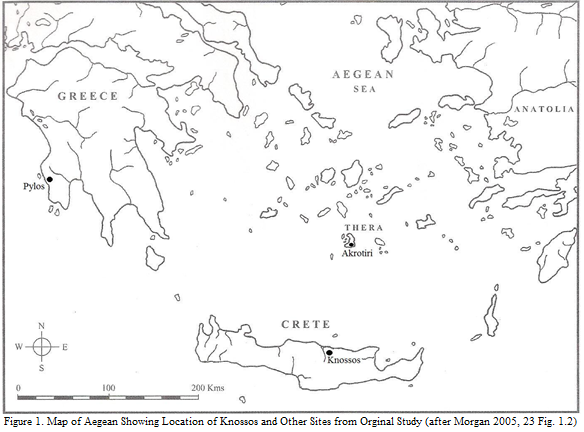

As a part of the original dissertation, three sites—Knossos, Pylos, and Akrotiri—were chosen to form the basis of this investigation of artistic and architectural characteristics, however, for this project, only Knossos was selected to be the subject of GIS analysis. While important in their own right for a comparative study, Pylos and Akrotiri not only cannot match the size and scope of Knossos, but lack the volume and diversity of frescoes and architectural features that make Knossos such an ideal candidate for a GIS approach. Furthermore, obtaining satellite imagery of Pylos and Akrotiri is also problematic since both sites have protective structures covering them.

While this study is a specific examination of Knossos, the results are not meant to interpret all important areas within Late Bronze Age Aegean sites. The focus here is restricted to the primary spaces that are well understood to have conveyed a powerful meaning to those who resided within their walls. Additionally, this statement is not intended to convey that, while these rooms are important, others are not, it is merely the acknowledgement that some rooms receive more attention than others due to the indication of ritual usage of space and administrative power.

A few Notes on Terminology

It becomes necessary to make a few remarks in regards to the terminology commonly used in the field of Aegean archaeology. From their first association with sites in the Aegean, the terms ‘Minoan’ and ‘palace’ have carried with them particular assumptions and connotations that are problematic today. Although Linear B tablets relate some aspects of the administrative organization on Crete, only in the case of Pylos do they actually confirm a palatial aspect to the site.

The heavily laden term, ‘palace’ has become synonymous with the monumental Bronze Age structures in the Aegean where it was assumed that powerful kings and rulers once resided. However, the main problem that is derived from this label is the political connotation that the term implies (Preziosi and Hitchcock, 1999, 89). Although much work has been conducted at these sites, the administrative configuration of these so-called ‘palaces’ remains largely unknown. Using the term palace conjures up a monarchical imagery that can in turn influence the interpretation of the rooms and their functions. With this caveat in place, I have still elected to use the term ‘palace’ in situations where it should only imply a description of the sprawling architectural layout and its dominance in relation to the landscape it occupies, not its political bearing or affiliations. Additionally, the use of terminology such as ‘Throne Room’ should not denote the acquiescence into a palatial ideology, instead it acknowledges that the room in question most likely was the location of some form of administrative control or authority. The type of figurehead or administrative system that was in place is beyond the scope of this project with the exception of its above influence over terminology.

The term ‘Minoan’ implies a similar set of problems, suggesting a unified Crete-wide adoption of ethnic identity and material culture under a single affiliation, allowing the expansion of material culture outside of Crete to be traced back to a single ‘Minoan’ source. Broodbank (2004, 50) argues that there is no archaeological evidence to support the hypothesis that the people of Crete were in some way united under a central authority and embodied a single culture. Following Broodbank’s advice, the term ‘Cretan’ should be applied rather than ‘Minoan’ in instances where a designation between ethnicity and material remains should be made clear. However, wall paintings at Knossos exist over a long time span which covers both the Minoan and Mycenaean occupation of the site. In this case, as a chronological tool, I have still implemented the usage of the term Minoan.

Background

Archaeology of the Late Bronze Age Aegean affords seemingly innumerous opportunities to the study of well documented Minoan, Mycenaean and Cycladic sites. However, there are arguably only several sites which may come to mind which represent the criterion of an abundance of frescoes, monumental architecture and detailed site preservation; chief among those Knossos (Fig. 1). While the foundation of this study is squarely centered on the iconographical and architectural features of this site, presented here is a general introduction to Knossos so as to become familiarized with the concepts, locations, and details of the site which are referred back to later in the text. Additionally, for a full account of details of each room, more information can be found in Appendix A of this report which lists each room type.

KNOSSOS

When Sir Arthur Evans first began excavations at Knossos in 1900, he gradually began to uncover a site whose towering edifices and labyrinthine layout led him to name the site after the legend of the Minotaur and the fabled King Minos. At a time when archaeology was influenced much by the classical works, Evans took his cues from Homer and believed Knossos to be the seat of power and religion for the Minoan empire. His conclusions, whether viewed as beneficial or detrimental, have ultimately shaped and influenced the interpretation of this site as well as Aegean archaeology. In this regard, the terminology, dating, and general interpretation come from in large part Evans’ vision.

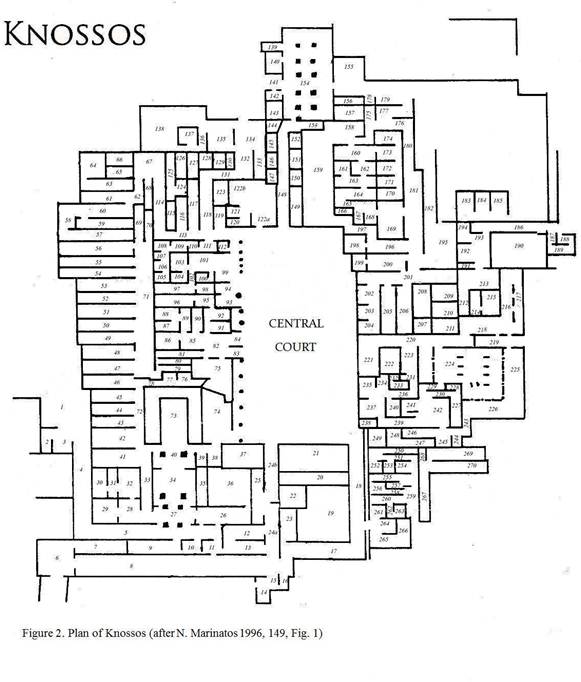

Situated in northern portion of central Crete, Knossos (Fig. 2) has come to occupy roughly 20,000 square meters, making it the largest site on the island (Bentancourt, 2007, 107). Due to the immensity of the site, many of the rooms will not be discussed and attention will only be drawn to a few important areas. The site as seen now surrounds a great court, which simultaneously acts as the nucleus and funnel to the rest of the palace, spreading out in each cardinal direction. To the west lays a main entrance whose famous Corridor of the Procession (Room 4) leads directly to the central court but also allows access to both the upper floors of the structure as well as to the West Magazines (Rooms 44-63); the storage facilities of the site. Additionally the western portion of the site is also the location of the Throne Room (Room 101), where the reconstructions of the famous Griffin frescoes are located. Moving to the North, the great North Entrance Passage (Room 148) is flanked by the famous East and West Bastions, one of which depicts a charging bull carved in relief.

In the eastern side there are a number of various other workshops, storerooms and most notably, the domestic quarter. Here, among many other prominent rooms are the Hall of the Double Axes (Room 224) named so, for the incised mason’s marks along the walls, as well as the Queen’s Megaron, (Room 242) the conjectural quarters of a high lady. Lastly, in the south, following a long entrance corridor and past the Prince King and Palanquin frescoes (Rooms 24a and 24b), a large ramp (Room 18) connects this area to the central court.

In terms of chronology, accurate dating is somewhat difficult to determine for Knossos because the dates for Crete are based on a relative chronology of Egyptian and Near Eastern king-lists. As such, the dates given here are meant to convey a general timeframe and not definitive chronologies, as this topic is well entrenched in debate. The timeline is a combination of ceramic styles as defined by Evans as well as several rebuilding phases that occur at Knossos after some form of catastrophe such as earthquake or fire and are used as indications of new architecture. Immerwahr (1990, 6) notes five distinct destruction phases that occur at Knossos, which allows somewhat reliable dating for the pottery and fresco remains found in these contexts. The periods of MM I to MM III correspond to the Proto-palatial Period, the dates of which are roughly 1900 to 1700 BC and includes the first major catastrophe. MM IIIA on through LM II are taken to be part of the Neo-palatial Period which encompass a time frame of approximately 1700 to 1450 BC and include the destruction horizons of the three other rebuilding phases. The last destruction happens around 1400 BC and marks the occupation and arrival of the Mycenaeans (Immerwahr, 1990, 6-8).

As noted before, the term ‘palace’ has led to the speculation of political control on Crete, however with the absence of any records to indicate organizational control it is unknown whether Knossos ruled as a hegemony or as a member of ruling peer polities, each governing their own territory. Knappett and Nikolakopoulou (2005, 178) argue that during the transition from the Proto-palatial to the Neo-palatial Periods, Knossos rose out of a system of peer polities to become the dominate figure in control. They believe that the benefits of switching to a more centralized authority may have been an attempt to develop a better system able to secure firmer holds on valuable natural resources outside Crete’s shores. Others like Wiener (1990, 140) take a more stylistically motivated approach, arguing that Knossos had indirect authority as the leader of fashion, style and belief in what he terms the ‘Versailles Effect’. He asserts that evidence of this is found in the abundance of Knossian seals found at other palatial sites on Crete, the widespread use of Linear A and the dominant size of Knossos.

With direct reference to this project, the map used above (Fig. 2) was used as a means of numbering each room. In the absence of a numbering convention for all the rooms, I created the above numbering for reference and cataloging. Given the complex layout of Knossos, I chose a less detailed map to use for the purposes of referencing the rooms discussed in this paper as well as a layout that reflected the ground floor and thus the best layout for showing the locations of frescoes.

FRESCOES

Aegean wall painting is a unique insight into the Minoan and Mycenaean world, a window onto the past, giving voice to the silent figures and scenes depicted on the crumbling walls of ancient cities. Capturing what the written word did not, these murals are the closest link to life in the Late Bronze Age, revealing elements about daily activities, religion and rites of passage. The investment of time, labor and costly materials necessary to produce them attests to the skill and complexity required to achieve these works of art. These frescoes represent more than mere decorative pieces, but the iconographical symbolism of Aegean beliefs, history and religion. For these reasons, wall paintings are considered in this study to be the foremost indicator as a feature belonging to a room of importance. As such, understanding of the nature in which they were created and the meanings behind their depictions become important to interpreting the importance of the space they occupy.

Conventions and Typology

As Morgan (1985, 7) explains, each culture constructs its own set of conventions for imparting cultural traditions that can often represent a set of ideologies which when reflected through pictorial representations are ambiguous to decipher. In this light, much work has been done to understand Aegean wall painting—often as Morgan (1988, 10) states, done in reverse approach—reconstituting the cultural beliefs of iconographical remains in the absence of a historical record. Through this study, much has been learned about the nature of Aegean frescoes generating the realization that they represent more than just mere decoration, but a set of typologies and conventions for displaying the socio-religious nature of the culture that created them.

Types

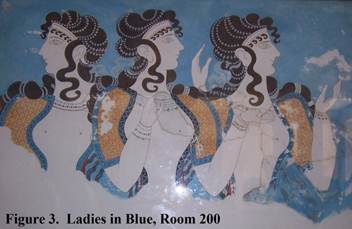

According to Immerwahr (1990, 40) Aegean wall painting can be classified into three main types: nature scenes, human figures, and miniature scenes. Nature scenes typically include a variety of plants and flowers with animals sometimes participating in human activities. Typically human figures are not present in nature scenes although Immerwahr does note that sometimes there is an arrangement between human and animal in which they occur in the same setting. The second class of frescoes are those that depict life-size human figures engaged in various activities. Of these, the majority of human figures are women and girls, although in some cases it is not clear if the female depicted is an ordinary woman or a goddess. Lastly, the miniature frescoes combine the previous two types, showing humans and nature but in small scale depictions. Immerwahr asserts that the majority of these scenes depict the many facets of daily activity ranging from festivals to pastoral life. These three different categories can be found at Knossos.

Configurations

The composition of the frescoes and their placement on the walls has been difficult to determine in many cases, however the detailed preservation at sites like Akrotiri have led to the ability to argue with some certainty a general pattern for the configuration of frescoes. Wall, window and door construction typically dictated the placement of wall paintings, and in many cases served as guide and border to frame the fresco. Immerwahr (1990, 13) identifies two basic wall schemes that serve as the general format for defining the area onto which the fresco was painted. The first scheme features a protruding stone base called a socle or dado that formed the lower portion of the wall that was often painted. The top portion of the wall was generally allotted a small band used for a border, leaving a generous portion of uninterrupted wall space for the main fresco scene. In cases where a door or window occupied the wall, a second scheme was employed. A wood lintel resting horizontally above the door created a space for a frieze to act as a border. Door and window framing created adjacent panels or wall space for the main body of the frescoes to occupy while the window sill also offered a place for painting as well. In this situation a dado also existed to define the space around the base of the room.

Looking at it in a different way, Palyvou (2000, 417) divides the configuration of space into three sections, the upper, middle and lower areas. These zones constitute the placement of frescoes on the wall in relation to the architectural space of a given room. In this way, the upper and lower boundaries both define and add to the visual imagery of the room. The lower and upper zones serve to unify the adjacent walls through horizontal bands of colored stripes or spiral friezes. The main body of the wall is devoted to the middle zone, where the main subject of the wall painting is placed, designed to confront the viewer when entering the room. While these schemes are based on the reconstructions at various sites, they should be considered as only a general guideline and not as a way to approach each scenario.

Artistic Conventions

The artistic conventions pictured in the frescoes at Knossos have a particular way of denoting age, gender, and animals that become necessary to note here because of the importance that these factors had in determining the functions and importance of rooms. A few examples follow to illustrate the use of these conventions, how they have come to be interpreted, as well as some of the problems these reconstructions have posed.

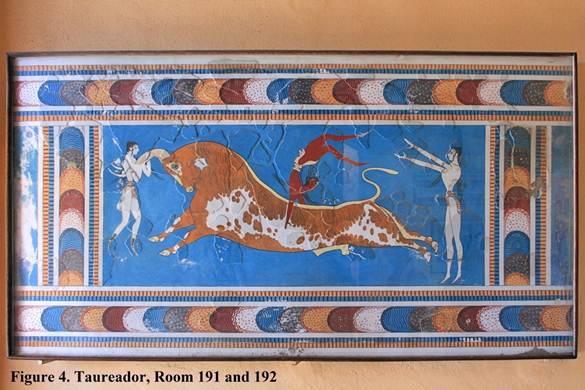

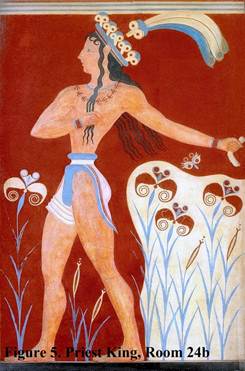

Borrowing from the Egyptians, Aegean wall paintings use particular colors to indicate male and female sexes. If painted in red, the figure is meant to be regarded as male, while plain white signifies that the individual is female (Preziosi and Hitchcock, 1999, 98). Seemingly straight forward, this color scheme has led to the misidentification of some frescoes such as the “Priest King” and Taureador frescoes at Knossos (rooms 24 b and 191/192 respectively). Due to the fading of color and the fragmentary preservation of these frescoes, it becomes difficult to interpret their original design and gender classification which has led to host of varying interpretations (Preziosi and Hitchcock, 1999, 99).

Another instance in which misinterpretation was the result of the color scheme employed by Aegean artists, is the fresco called the Saffron-Gatherer at Knossos (room 122b). First discovered by Sir Arthur Evans, this fresco was first identified as a blue boy. However the finds of blue saffron-gathering monkeys at the House of Frescoes near Knossos as well as at Xeste 3 at Akrotiri show that the so-called boy was in fact a monkey. Perhaps substituted for the Egyptian depiction of monkeys as green, Aegean artisans used blue to convey these animals (Immerwahr, 1990, 41).

In addition to color schemes, hairstyle also played an important role in determining not only gender but age as well. Davis (1986, 399) classifies the hairstyles into six progressive stages of maturity. In the earliest stage, those that are youngest are shown with their heads shaved, visually represented as blue, typically with a few locks remaining on the head. As the youth matures, additional locks on top of the head are allowed to grow indicating the child is somewhat older. A sign of full maturity is depicted when the women’s hair is full, long and flows down the back.

Technique and Process

After the construction of a wall, the surface was generally covered with a layer of lime plaster and spread evenly across the face of the interior, followed by a second coat of the material upon which the frescoes were to be painted (Hood 1978, 83). From here the process becomes one of debate, as the technique by which the paint was applied to the plaster was conducted in one or two methods requiring various levels of skill and knowledge to properly execute.

The application of paint onto wet plaster, termed buon fresco is achieved when the pigments from the paint are fixed to the plaster through the process of carbonization of calcium hydroxide. The other technique, called secco fresco, is when paint is applied onto dry plaster (Evely, 1999, 148). While both techniques can achieve a similar look, the former is considered superior due to not only the higher level of artistic complexity, but to the unique bonding that is created between the paint and lime in the plaster that creates a durable and long lasting work of art.

Evidence of string imprints in the plaster indicate the use of guidelines to position the fresco in the proper layout on the wall. Done while the plaster was still wet, this is another indication that the wall paintings were done in buon fresco style (Hood, 1978, 83; Immerwahr, 1990, 14). Additionally, work done by Cameron in the laboratory to replicate the buon fresco technique was met with success when the paint surface did not dry as rapidly as had been thought, allowing the artist ample time to apply the paint. Once the paint dried, the experiment showed that the pigment had bonded to the plaster and resisted water damage (Cameron et al. 1977, 160). Further work done by Cameron also showed that under microscopic magnification, samples of painted plaster showed a solid bond to the plaster in most cases, indicating that the paint was applied while the plaster was still wet. Although buon fresco was considered to be the primary technique in which Aegean wall painting is done, there are some instances in which the study done by Cameron demonstrated that secco fresco was employed as well (Cameron, et al. 1977, 161).

While the technique may have varied from site to site, the manufacture of the plaster and pigments as well as the application of the procedure was undoubtedly immensely time consuming (Evely, 1999, 152), suggesting that wall paintings were not merely the affectations of a wistful décor, but the indelible markings of a socio-religious influence indicating rooms of significant importance.

Religious Context and Rituals

Proceeding in the context of associating religious and ritual ideology to iconography should be done carefully to say the least. There is more unknown about Aegean wall painting than there is known to archaeologists, so interpretations are subjective and somewhat tenuous at times. However, certain architectural features working in tandem with the subject matter of the frescoes has led to the possible interpretation of religious or ceremonial material in some cases, while in other instances stylistic clues are used to acquire meaning.

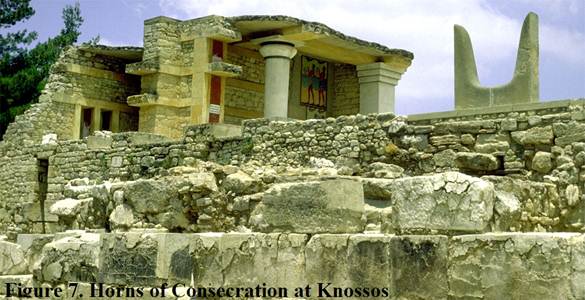

While most of the most famous linkages between religion and rituals come from Akrotiri, cultic equipment and architectural features such as lustral basins, pier-and-door partitioning and the horns of consecration, are all found at Knossos, heralding religious and ritual activity.

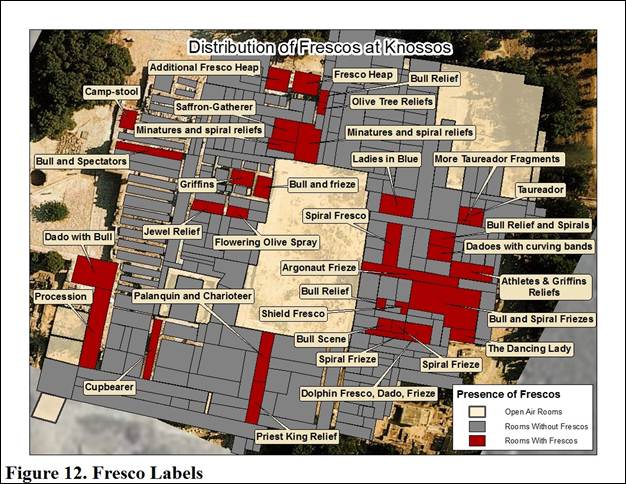

The Frescoes at Knossos

Below is a brief summary of the major pictorial programs from Knossos and some examples. This is not meant to be a detailed survey nor a catalogue of wall paintings, simply a way to layout the general details of the frescoes so that they may be referred back to by design, type and motif. The information below should also be used in conjunction with Table 1, wherever details of the fresco descriptions are vague. Additionally, it may be important later to draw upon particular features of some of the themes listed here now. For a more detailed account of the frescoes at Knossos, Hood’s article (2005, 45-81) provides an excellent overview.

The frescoes from Knossos can be classified into thematic sections which represent various aspects of the culture and world which surrounded the inhabitants of the site. Following N. Marinatos’ (1996, 150-157) review, the wall paintings can be classified into the following subjects: ideology and power, festivals, high status females, athletes and males of authority and finally nature scenes.

Power is represented through the depiction of bulls found in rooms 4, 148 and 99. They may have conveyed a symbolic representation of the force of nature. Scenes of festivals were captured in miniature in the rooms north of the central court (121 and 122a). An example of high status females is seen in the Parisienne woman from room 58, the goddess figure from room 4, and the Ladies in Blue in room 200 (Fig. 3). The famous Taureador fresco from rooms 191 and 192 (Fig. 4) represents an example of athletic frescoes while other powerful male figures include the individuals from the Palanquin fresco and the Priest King fresco (Fig. 5); rooms 24a and 24b respectively. Lastly, scenes of nature such as the Saffron Gatherer, comes from room 122b.

ARCHITECTURE

Perhaps not as deliberately stated as the vivid frescoes that adorn the walls of Knossos, the architecture of each site yields important aspects as to the function of a room, its purpose and significance. In many cases the architecture works in conjunction with frescoes to compliment the physical placement of the paintings on the wall as well as suiting the activity suggested by the fresco to have been carried out in the space of the room. As Driessen (2004, 76) suggests, architecture reflects the investment of social resources and embodies political, religious and economic power. Having this power to limit and grant access, to affect ones sense of perception and to dictate the activities carried out in the space, reveals that the architecture of a building is certainly a defining factor for rooms of importance.

Defining Space in Late Bronze Age Architecture

Perhaps in the absence of the written text, architecture may be the most telling insight after wall paintings into the Late Bronze Age Aegean. The reading of what Tilley (1994, 14) refers to as ‘spatial text’, is the ability to extract meaning from the monuments and landscapes. According to Tilley, the effects created by architectural space as well as the experiences that occur in those spaces are all imbued with social meaning. Certainly the lustral basins, processional corridors, Throne Rooms, and Megara at Knossos can be read in such a way. Gheorghiu (2001, 25) defines space in a similar way as “the phenomenological result of the configurational and symbolic relationships between building, fixed and mobile objects, and human body throughout the performance of a rite of passage, set by the boundaries of the constructive elements”. Like Tilley, Gheorghiu argues that architecture is imbued with particular information about the culture and society that crafted it, allowing one to read the unwritten story in the stone. Gheorghiu notes these observations can be most comprehensible in architectural spaces that involve ritual functions, particularly rites of passage. Nowhere are examples of this type of readable architecture more prevalent than in the Late Bronze Age.

The Neo-palatial Period is a time that Palyvou (2000, 414) refers to as the ‘Golden Era’, when architecture becomes a combination of both function and aesthetic. Palyvou argues that at this point, architecture and art begin to harmoniously work together so that the outcome is one “of a sophisticated design process meeting the functional and aesthetic demands of an equally sophisticated lifestyle” (2000, 414). These places, where architecture meets with iconography to conduct ritual and societal practice, is the place where rooms of importance are to be found. In regard to these locations and architectural features, what follows is an acquaintance with these particular elements, their functions, and how ritual and social activity is defined by their composition.

Specific Architectural Features to Note

The construction of architectural areas and features can suggest the functional aspects of built space, while the level of elaborateness, skill and craftsmanship indicates the importance of such features and areas. Certain forms of Late Bronze Age Aegean architecture are highly indicative of ritual function and the formation of elite spaces which typically occur in conjunction with wall paintings. Combined with this iconographic evidence, these features further attest to the intentionality of creating a space of importance.

The Central Court at Knossos has been referred to as the “most distinguishing and indispensible ingredient of what makes a Minoan building a “palace”’ (Driessen, 2004, 76). Certainly ubiquitous in Minoan architecture, the Central Court at Knossos undeniably commands a large presence. As a standard installation in palatial construction, the open air court where public activities were conducted, remained bordered not by walls but by the facades of the surrounding buildings. Davis (1987) argues that the miniatures frescoes found just north of this open area, in rooms 121 and 122a, are pictorial evidence for the function of the Central Court. The depiction of a crowd of people, assembled in the court is portrayed, possibly gathered for a special ceremony. This, Davis asserts is what the Central Court was designed to do, to accommodate large masses of people for ceremonies. As such, its importance was more as a communal space rather than a room, its purpose, incorporating the landscape and nature, creating an outdoor facility for rituals and social activities to take place (Driessen, 2004, 76). For these reasons the Central Court is not factored into the room average, however this should not downplay the influence this area had on the construction of the rest of the site. In this view, areas which connect and interact with the Central Court, such as the entrances, are seen as important due to their connection with such a culturally significant place.

Equally as well known as the Central Court, the Throne Room (Fig. 6), room 101, has become an icon of Knossos, with its stone seat flanked by imposing griffins done in fresco. This room was of great importance as evidenced by its luxurious frescoes and architectural features. The Throne Room area may have been were a set of rituals were performed, a place for an epiphany cult as Niemeier (1987, 163) suggests, with the various adjacent rooms acting as preparation rooms for the ritual, while a goddess figure presided over the throne. A lustral basin or adyton lie not far, where these rituals may have been carried out. The area’s proximity to the Central Court guaranteed a close involvement with the social activities being conducted there and may have been a part of the ritual functions carried out there. However, one additional feature may highlight not only the significance of this room but its intentional placement at the site.

In an attempt to read the spatial text of Knossos, Goodison (2004) argues that the Throne Room at Knossos held spatial significance in relation to its astronomical positioning. She points out that there are certain times during the year when the sunrise projects its light directly into the Throne Room to highlight particular architectural features of the room. During the winter solstice, the sun’s rays project into the room to light up the throne, while during the summer solstice they shine into the lustral basin, suggesting that there may have been some ritual significance associated with the sunrise (Goodison, 2004, 343). During the spring and autumn equinoxes the sun shines directly down the length of the area creating a straight line through the Throne Room. These effects works in conjunction with the architecture of the Anteroom to the Throne Room since its east wall was constructed as a polythyron. Composed of pier-and-door partitions, the wall was designed to be opened to the east to capture the light from the rising sun. Additionally, Goodison states that due to the height of the ceiling, the sun’s rays would have only been able to shine into the room for a few moments in the morning suggesting a brief but significant occurrence (Goodison, 2004, 143). Whether ritual was associated with the Throne Room’s spatial orientation is subject to debate, however what is certain is the high level to which the architectural features of the Throne Room were regarded, so as to construct a precise layout that would have allowed astronomical alignments to factor into their placement and creation. The combination of features present in the Throne Room at Knossos serves to only highlight the significance of frescoes and architecture in a room of an importance.

The lustral basin or adyton as mentioned before is another highly important architectural feature found at Knossos. Sunk down into ground, the lustral basin was a small L-shaped room reached by a series of steps leading to a stone-paved base platform flanked by pillars and ashlar blocks (Palyvou, 2005, 57). No drain has been found in the floor which seems to suggest that the occupant was bathed, however N. Marinatos suggests that small amounts of water may have been poured over the figure as part of ritual procedure (1984, 14). The best examples of this feature in ritual action are seen in rooms 100 and 137 at Knossos. The close proximity to the Throne Room and the Northern entrance at Knossos suggests that the lustral basin was regarded as an important feature both for the private use of the ruler as well as visitors to the site, suggesting an important societal function.

The horns of consecration (Fig.7), most famously depicted at Knossos, are typically viewed as the most important form of religious symbolism in the Minoan world (Gesell 2000, 947). The horns, taken to represent the sharp projections of a bull’s head, are found in various contexts and locations, ranging from roof-tops, tombs and shrines.

Public and Private Space

In reference to public and private space, it is difficult to completely ascertain the level to which space was defined in the Late Bronze Age since these concepts are heavily laden with culture specific ideologies. However, there is a usefulness in attempting to analyze the notions of public and private space in order to better understand the functions of these sites and how people may have interacted with their surroundings. Due to the importance of ritual and celebration which was most likely carried out in public spaces, it becomes invariably difficult to make a distinction between the importance of rooms considered private and those public. However, by labeling these distinct positions in conjunction with the other features which I have argued constitute a room of importance, it may be possible for architecture to dictate the use of public and private space. Certainly, not many rooms could have rivaled the importance of the Throne Room at Knossos or the Queen’s Megaron. And while it may be difficult to assess how they ranked against public spaces such as the Central Court of Knossos, their nature was undoubtedly private. In an attempt to formulate a type of methodology I have employed a classification system that follows Palyvou’s (2004) discourse on architectural spaces. As such I feel confident in labeling those rooms considered of importance to this study as ‘private’ or ‘public’.

Following the outline first put forth by Chermayeff and Alexander (1966), Palyvou (2004, 207) reworks the architectural models for public and private space in Minoan architecture into six categories ranging from the most public to the most private. The first category is ‘urban public’, this would be communally owned property such as roads. Next is urban ‘semi-public’, areas that are available to the public but that are also controlled and regulated by the government. Following this is ‘group public’, a sort of liminal ground between public and private space that requires participation from both sides, such as utilities control. Progressing further on are the two most private categories: ‘family private’ and ‘individual private’; the former relating to space controlled by a single family, while the latter pertaining to an individual’s own retreat away from the world. While the majority of these categories are meant to represent a broad spectrum of architectural features present outside the evaluation of this study, my application of this methodology will be restricted to a few of the categories. In applying this model to the study of Knossos, I believe it useful to classify the architectural spaces under such pretenses in order to grasp the accessibility to the rooms in question. Taking the cue from Palyvou, public places such as the Central Court at Knossos is considered to have been an urban ‘semi-public’ space while ‘group public’ areas for example would have been areas like the lustral basin in room 137 near the North Entrance that may have been used by the public. In contrast, private areas such as the upper floors of buildings and verandahs fall under the category of ‘family private’ but do not meet the nature of ‘individual private’ spaces such as the small courts adjacent to the Queen’s Megaron. These areas are considered a total escape from the public, where the inhabitant could occupy the space without the presence of others. While it does not bear prudence to go over every such example of public and private space at Knossos, the above methodology was applied to determine the accessibility of each room in question. Below follows a few notes and exceptions with regard to the site, as no single methodology serves as a blanket statement for every scenario.

The nature of public and private space at Knossos is difficult to determine since the general layout seems to convey a particular focus on the Central Court. As noted above, this feature of the site was most likely the location of public ceremonies. Based on this, a majority of the site must have remained open to the public, especially due to the amount of staff that would have been required to run the facility and their need to freely navigate the palace. However, there are a few exceptions in which private or restricted access was designated. For instance, the lower eastern portion of the site considered the private residences of a high lady, were most likely not available to the public. Additionally, the Throne Room and adjacent rooms, were most likely restricted to a small number of visitors. With this general outline, the formation of public and private space must center around this configuration.

Methods

The body of this paper has hopefully illustrated not only the inclusion of various elements that constitute a room of importance at Knossos, but the practicality in choosing this site based on the abundance of said features. With an understanding of the mechanics, purpose and features of both architecture and wall painting at Knossos, it is possible to navigate away from an attention to the particulates and onto the rooms themselves as viewed in a broader spectrum.

Below is a table which seeks to compile the qualitative assessment of importance into a valid data set based upon the above features at Knossos. An amalgamation of data is then presented reflecting statements of percentage based figures denoting observable patterns, trends and majorities.

While the vast scope and sheer volume of Knossos presented a challenge in creating concise measureable data, a table was first created to gather a basic knowledge of the rooms, which can be found in the appendix of this report (Appendix A). This table reports the dimensions of every room within the main complex of Knossos showing the presence of frescoes when applicable. As demonstrated, frescoes are considered the primary criteria by which rooms of importance are highlighted due to their abundant preservation as well as the high status by which they were regarded. Due to the fact that frescoes can be found in corridors, lavatories, stairways and in many other architectural areas, I felt it necessary to measure all the architectural spaces at each site (corridors, stairways, halls, entrances, etcetera). Another reason behind this measuring decision was to have enough statistical data to compare the average room size to the average room with frescoes. Also of significance is the type of each room measured, which is listed on the table in order to extract a correlation between room type and fresco. Instances in which there is not a designation for room type indicates the lack of a definitive function or discernable purpose for the measured space. From the collected data the average size of each room is calculated as well as the average size of all rooms with frescoes in them. It is important to emphasize that the average room size is the average size of all rooms including those that contain frescoes. This was done in order to report the average room size at Knossos not the average size of rooms without frescoes.

Once the preliminary data was collected, then an additional table was created which shows further details about the rooms with frescoes. Table 1 shows in addition to the room size and type, secondary features which are used in correlation to the presence of frescoes to highlight the room’s importance. Reported here is the construction of the rooms, any architectural features, descriptions of the frescoes, the room’s accessibility and floor level, as well as the tentative date of each fresco. The general purpose of this table is to put forth a concise list of the frescoes from each site while at the same time presenting a descriptive list of details about their provenience. Each category represents specific information that when combined with the other details, creates a better understanding of the context in which the fresco was created.

As mentioned, information about the construction of a room can say much about the importance of the space, especially if high quality techniques such as Ashlar are employed. Architectural features such as columns and baths can also show an investment of time and labor into creating a luxurious space. While these features speak to the actual construction of the room, there is much to be said about the location and accessibility of the frescoes. These categories help create an understanding of how people may have interacted with the frescoes, whether they were for private viewing—cut off due to status or membership restrictions—or whether distance may have been a factor; frescoes positioned on upper levels may not have been as readily seen as those on the lower floors. Additional criteria such as the description of the frescoes and their dates can further highlight details about the room and its significance as seen from the ceremonial and religious examples.

It is the ambition of this report to compile this data set in order to substantiate the claims espoused in this paper that there is a high degree of correlation between room size and rooms of importance, i.e. rooms containing frescoes, architectural features and high quality masonry.

Considerations – Maps and Sites

It is important to note that the measurements of the rooms at Knossos are a close approximation derived from measuring rooms on a to-scale site plan. While I endeavored to be as accurate as possible, there will inevitably be a slight deviation in the actual size of the room if taken by an on-site measurement. While these measurements are as precise as can be reported, it should also be noted that due to various interpretations of the site, and thus slight differences in site plans, there will invariably be a minor disparity in the size of each room from plan to plan. For Knossos, the sheer size of the complex as well as the vast number of rooms, led me to use the map previously noted (Fig. 2) as a means of numbering the rooms. While this map is not as detailed as others, its more simplistic drawing made the identification and numbering of rooms much more feasible. In reference to the Corridor of the Procession at Knossos, the basement floors were purposely not measured in order to recreate a site plan that reflected the circumstances in which people entering from the West Entrance would have walked along the path as well as the environment in which the frescoes would have been seen.

At Knossos, the focus is on the main complex and as such, the additional buildings outside the complex such as the South House, the Caravanserai building, and the House of Frescoes are excluded. While the presence of frescoes in some of these buildings is both impressive and important to the overall study of wall-paintings in the Aegean, for the purposes of this study, due to their location outside the walls of the main structure, the houses were taken out of consideration because they were off site and not subject to the same criteria that may have guided the construction of rooms of importance within the walls of Knossos. Additionally it is not known what type of residents may have inhabited these houses and whether their ideas of importance were the same as those conveyed at Knossos.

Lastly, in reference to these sets of tables it should be noted that as with any report based on large amounts of numerical data, the figures are always subject to change and as archaeologists produce clearer pictures of these sites, it will be beneficial to update this report as new findings are unearthed.

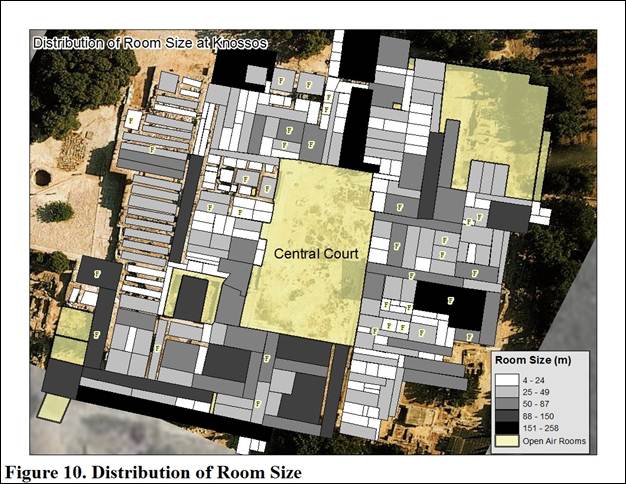

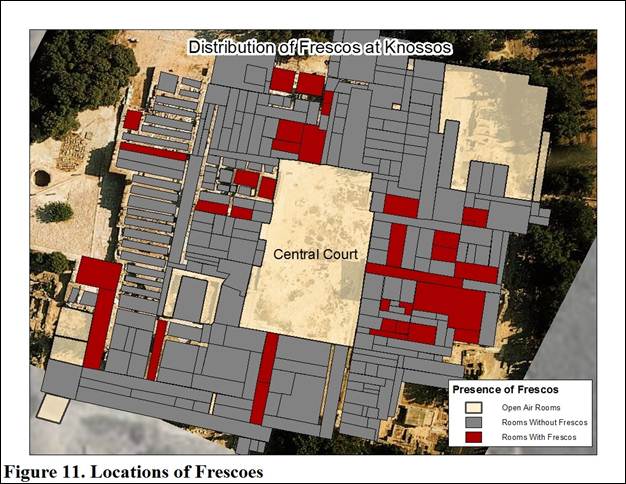

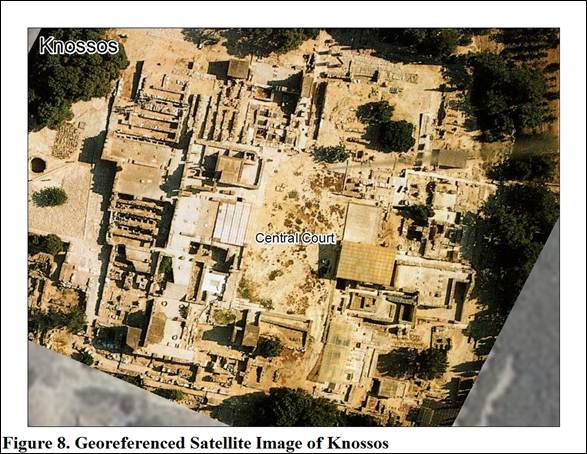

Implementing a GIS

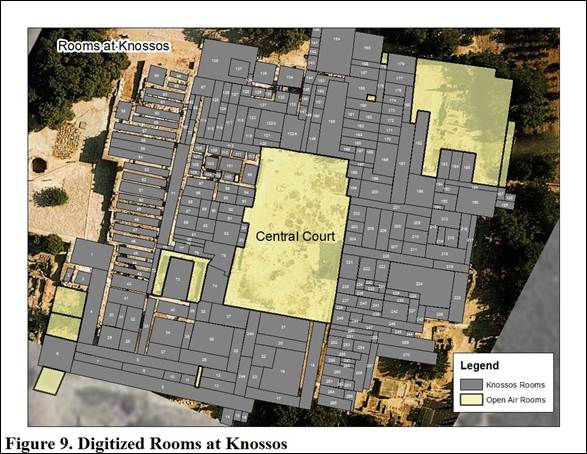

Once the data on Knossos was gathered, I took the best available satellite imagery (Fig. 8) of the site and georeferenced the image in ArcMap onto a basemap which showed the site but in low resolution. With the higher resolution imagery I then began the process of digitizing the rooms one by one following the site plan of Figure 2 and compiling all of the data from Table 1 and Appendix A into the attribute table in ArcMap. Once this was complete, I then had a spatially referenced site map of Knossos with a complete database of each room and what was contained therein (Fig 9.) Additionally, the ability of ArcMap to calculate the area of each polygon would have rendered the previous step of measuring each room unnecessary, however it did provide a guide in correctly digitizing each room. From here, using ArcMap I was able to symbolize the data and generate both thematic maps of fresco distributions as well as choropleth maps to show size distribution.

Results

The site plan of Knossos is both immense and confusing at the same time. The remaining floor level is a conglomeration of artifacts and remains from both upper and lower floors making the interpretation of some areas difficult to ascertain. In some cases it is unclear whether fresco remains belonged to upper stories or ones below. Despite these challenges I have put forth the best information in regards to the position of wall paintings as well as architectural features in this data table (Table 1), however some details still remain controversial.

I measured 270 rooms at Knossos, comprising the areas surrounding the central court and found there to be 34 areas containing fresco remains. For the purposes of measuring room size, rooms 145 and 146 were not factored into the average room size as well as the average room size with frescoes because of their architectural nature as bastions. However, they were counted as part of the percentages for the results of rooms with architectural features, rooms with high quality construction materials, as well as the accessibility figures.

Knossos features a predominance of ashlar masonry used for wall construction and other high quality gypsum work typically used in stone floor-slabs, door jambs and pillar bases (Evans, 1930, 270). As such, of the 34 rooms highlighted, 24 of these were constructed in part with high quality masonry demonstrating a 71% occurrence in rooms with frescoes.

Elaborate architectural features remain a hallmark feature of this site, signifying the expert skill and craftsmanship of the builders at Knossos. Care and time was taken to construct the tapered columns as seen at the West Bastions (Room 146) as well as the ornate balustrades and colonnades of the Hall of the Double Axes (Room 224) and the Queen’s Megaron (Room 242). Of the 34 rooms chosen, 20 (59%) of them contained some type of