Census of the Dead: Investigating Patterns of Demographics in the Historical Matthew Kilgore Cemetery |

|

Author

Stephen Kadle

American River College

Geography 350: Data Acquisition in GIS Spring 2012

|

|

Abstract |

Numerous authors have stressed the importance of studying because they Cemeteries provide unique wealth of information for local historical societies, professional historians, archaeologists and local family doing genealogical work for people tracking there deceased descendants and as avenue to study culture change through time, most of the studies available in this regard have been general in nature and completed without any statistical analysis. The primary goal of this project was develop unique prototype project using GIS as source to document archival based historical spatial and non-spatial cemetery data that has been ravaged from neglect, vandalism and bad recording keeping. An alternative to a geographic information database can provide aid in preservation of spatial as well historical information for cemeteries and its need for subsequent retrieval for research of analysis on local area population dynamics to burial patterns that may not be apparent in research. |

Introduction

The human obsession with death, mortuary practices and the cemetery have long been topic of study as had the need for construction in the landscape to house the dead has some way or another been guided by the prevailing need for basic infrastructure to house the resting place for the dead as well their own cultural attitudes and values that have shaped their lives. Consequently, these tangible needs form discernible patterns that become inscribed and built upon the landscape that can be experienced and read by different audiences. These cultural constructed landscapes are thus reinterpreted through other cultural filters. For example cemeteries, these time-honored fundamental sacred places in the community, represent and even enhance sense if personal space and reflections of set values that are reflected in time and can also help reinforce the principles of traditions of given society that changed over time. As memorials, cemeteries are classically places for the living dedicated to the dead. Cemeteries may or may not contain the remains of buried. The cemeteries are created by the living individuals to remember loved ones. As a reflection of visual and spatial reflection of a social place for dead, cemeteries do provide information about the living culture that created them. Cemetery features such as headstone types and their arrangements are at the same time artifacts of landscape and represent metaphors reflecting the cultural traditions of that society in which these sacred landscapes originated. The archaeologist Edwin S. Dethlesfen had remarked, “A cemetery should reflect the local, historical flow of attitudes about the community. It is, after all, a community of the dead, created, maintained, and preserved by the community of the living” (1981:137). As the Dethlesfen quote goes, the subsequent treatment of these entities reveals much more about societal values and the treatment of our dead. This paper represents an attempt to duplicate this process in order to assess not only the required steps involved, but more importantly the level of accuracy that can be expected from historical research of a pioneer cemetery and as to what level of information can be derived from records to compliment them in geographic information systems is perhaps one the most prominent tools that can be used to offer up a tool for analysis on and use of deciphering pattern of data for use in historical preservation of early Pioneer cemetery feature data, if this is the case how accurate and useful this information can be used to deriving pattern to historical research data?

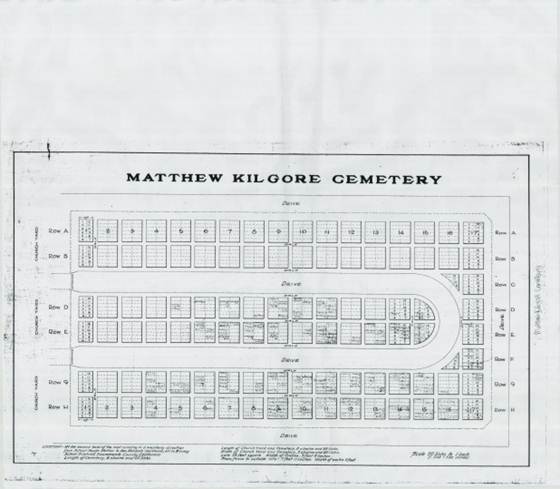

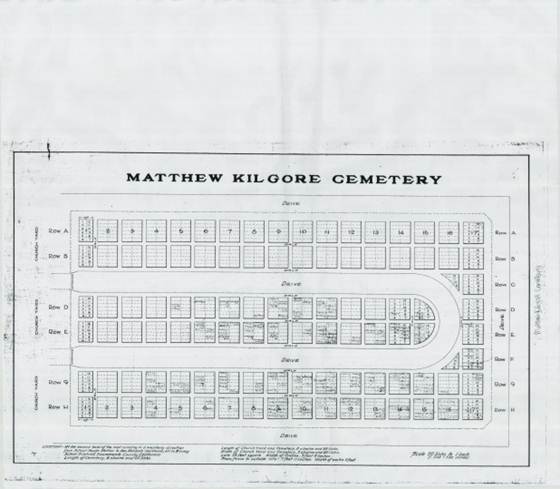

In order to address these questions, historical maps of what is now Matthew Kilgore Cemetery in Rancho Cordova, California were used in combination with a GIS and Historical records of non- spatial data to obtain accurate picture field assessment survey as well using what records are available to obtain a picture of any discernible patterns from incorporation in GIS. In short, this area is located on Kilgore Road between Trade Center Drive and Sun Center Drive where large industrial and business parks surround it. The Matthew Kilgore Cemetery has been laid in horse pattern block of burials representing twelve individuals per burial plot. This presented ideal opportunity in this area for a type of necessary cemetery analysis assessment.

Figure 1: The Location of The Matthew Kilgore Cemetery

Back Ground

The first recorded purchase of Matthew Kilgore Cemetery is recorded in a deed executed on May 12, 1874. Landowners James and Ann Locy signed and transferred the property to the original trustees, which included Matthew Kilgore, G.M. Kilgore, and G.A. Evans.

Figure 2: Matthew Kilgore and Wife Massa Kilgore

Prior to the establishment of Kilgore Cemetery, the first burial in what would become The Matthew Kilgore Cemetery, belongs to woman by the name of Marry Crites (Heppting Collection: 1944). Remaining area residents were buried in the Kinney High school schoolyard, and over process of 14 years burials were exhumed and re-interred at the current cemetery site of the Matthew Kilgore Cemetery. In some cases more than one burial was interred in more than one plot.

On March 26, 1888, the residents of the Kinney School District met at the American River Grange Hall for a special meeting to secure the future care and maintenance of the cemetery and settle a disagreement between Matthew and G.M. Kilgore, who would be the first elected head of the cemetery association. The group of individuals chose Matthew Kilgore and decided to incorporate their association and elect additional board of directors to draft Articles of Incorporation. These were recorded as the “Matthew Kilgore Cemetery Association Incorporated.” The cemetery was mapped and recorded on June 1, 1888 with the Sacramento Recorder’s Office. The Kilgore Cemetery association maintained and its board of directors worked for another fifty years until 1962. In 1962 and 1972, the Association turned over the property to Miller Funeral Home of Folsom, California. In return for the property, Miller Funeral Home provided care of the cemetery. In May of 1972, 18 members and board of directors decided to sell the property to Howard Keene and Dale Snyder in hopes that care for the cemetery would continue. Unfortunately, over the following years, neglect and a lack of interest caused the property to fall into disrepair given the bankruptcy of Howard Keene and Dale Snyder.

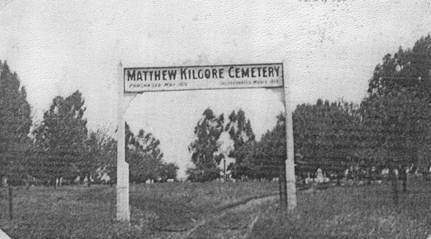

Figure 3: Courtesy of Center Of Sacramento History: Eugene Heppting Colleection 1929

Archaeologist, historians and others have made many uses of technologies in the past for analysis of prehistoric to historic sites whether large or small, so coming up with acceptable definition for Geographic Information Systems (GIS) as tools for the input, analysis and output of spatial data are hard question to isolate, According to KJ Duecker (1979) Keith Clark (1997).

“A geographic information system is special case of information where database consists of observations on spatially distributed features, activities or events which are definable in space as point lines, or areas. A geographic information system manipulates data about these points, lines and areas to retrieve data for adhoc queries and analyses “(Duecker, 1979: 106)

Taking the Duecker definition of GIS, a necessary well designed geographic information database for cemeteries would aid in retrieval of spatial oriented historical; based information for necessary retrieval based research analysis for archaeologist, historians, and genealogist.

A standardized database design would provide the necessary consistency for the needed consistency in documentation of cemeteries like Matthew Kilgore Cemetery for analyzing and querying data. The database or spread sheet would also make the most of current related available object relational techniques and flexibility and that is required to query for uses in other necessary case studies of historic cemeteries for analysis at varying scales with particular regard to integration for intra-site to that of inter-site level for such analysis.

Proposing any standardized digital storage form and retrieval based systems, Schafer (2004) touches upon a pressing central need of some form standardization for storing spatial and non-spatial attribute data. Schaefer used a different system than standardized ESRI GIS.

Schaefer’s ultimate goal was to integrate both spatial maps and non-spatial attribute material in such way that the information could be analyzed in an advanced manner. His maps were the first large scale mapping surveys of the land in United Kingdom. His maps were deemed accurate for legal purposes. Because the data is historical it can be considered comparable to Historical cemetery data. Schaefer use of non-spatial attribute and the maps allowed for analysis of local land use, property ownership, tenancy and local productivity. His ultimate goal was to maintain as much original information form the historical data as possible as it is entered into GIS Format.

For This Project a creation Pivot table joined to Shape File with attribute based data would joined to Kilgore Cemetery Block Shape file.

There have been several prototype cemetery databases with spatial features. Most of them have been used for managing cemeteries, but none of them seem to have necessary requirements, as City of Sacramento Old City Cemetery and the committee that manages this entity (http://www.oldcitycemetery.com/) in GIS and the Evergreen Cemetery in Fayetteville, Arkansas under direction Dr. Gregory Vogel: (http://projectpast.org/gvogel/Evergreen/Evergreen.html ) . Most studies have been used for management and documenting cemeteries for preservation purposes.

My definition of GIS for this project is an object to store various types of spatial and non-spatial data for convenience of data handling display and to perform spatial analysis. This project paper will not be providing a GIS database schema for basis of resource management, to provide orderly and consistent initial template for documentation. But, rather as instrument for querying raw data for historical analysis for cemetery that lost majority of historical documentation and which had been neglected and vandalized. Basic information for census would be entered into shape file with individual counts for census of sorts.

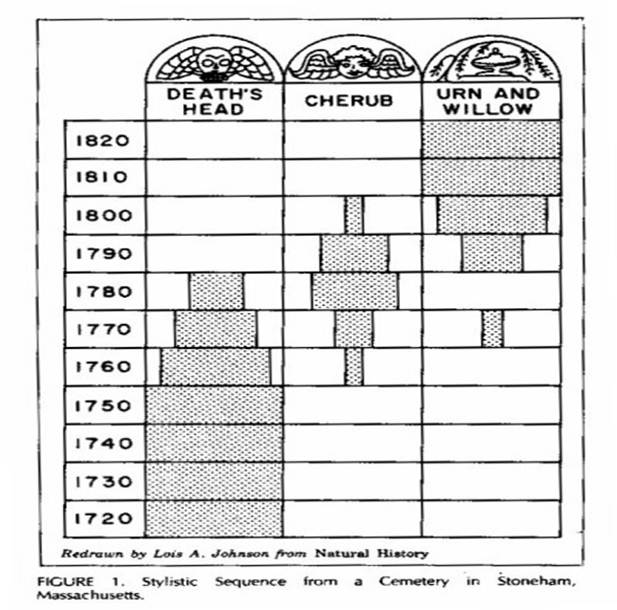

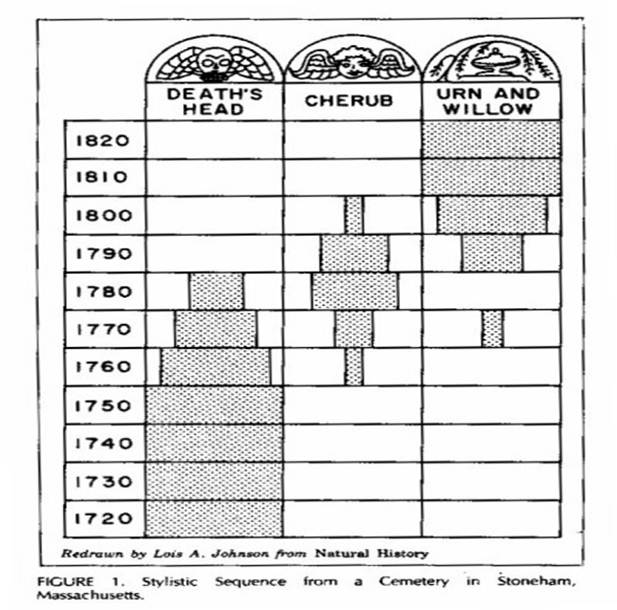

It has long been apparent that the resting place of the dead provides archaeologists, historians and genealogist and local historical societies’ considerable insight into the living community. Perhaps the first recognized study of American cemeteries was that Harriette Merrifield Forbes’ Gravestones of Early New England and the Men who made them, 1653-1800) (1927). In this first paramount work, she identified traits specific to select gravestones carvers and attempted to classify markers with respect to cultural and religious influences of the 17th and 18th centuries. While this has been considered to be monumental work for its first historical significant influence, it is said that as a historical foot note, that this work on cemeteries was not published until the 1960s. Two well-known known publications were released: Allan Ludwig’s Graven images New England Stone Carving and Its Symbols 1650-1815 and Archaeologist Deetz and Dethlesfsen Death’s Heads, Cherubs and Willow Trees: Experiment Archaeology in Colonial Cemeteries. Both of these publications examined the symbolism found on New England gravestones and observed that the symbols changed through time, seemingly in concert with changing prevailing attitude reflected in Puritan thought of this period. As Puritan beliefs gradually grew less imposing, so did the symbolism and epitaphs seen in the regional gravestones. Images of winged death heads slowly gave way to heavenly cherubs, and later to surprisingly secular based willow trees. The grave stone messages experienced a similar shift, through variation on the oldest traditional graven messages are still seen well into the 21st century.

Death’s Heads, Cherubs, and Willow Trees: Experimental Archaeology in Colonial Cemeteries. American Antiquity 31(4) 502-510

Figure 4:Death's Head, Cherub, Urn and Willow by James Deetz and Edwin S. Dethlefsen

Figure 5: Death’s Head

Most of the work of that has been done in cemetery research since the 1960s had largely dealt with changes in stylistic changes in the art of the stone carving or the way in which cemeteries have changed as a whole over the period. With regard to such studies this area of research has been general in nature and completed without formal use of statistical analysis, the only notable exception being Dethlefsen (1981) study titled The Cemetery and Culture Change. In this study Dethlesfen examines typological based categories such as stone size, stone messages and design motif and inscriptions. He hypothesizes that cultural traits represented by these typological categories, and that the use of these categories changes through time. Though his study deals with specifically cemeteries in Florida, His study does lay implication that these particular trends could go beyond a regional level of analysis.

It is hoped that using the Historic Matthew Kilgore Cemetery in Rancho Cordova will be useful study ground for analysis of variance, and frequency of available data gleamed from census data and assessed to test whether any type of data can still be recorded from this neglected cemetery could explain any form of patterning in population.

Cemeteries like that Mathew Kilgore Cemetery have suffered numerous problems without regular schedule maintenance which results in the loss of structures and other based cemetery objects such as the oldest unmarked graves and mausoleum. Statues monuments and markers degrade or break and knowledge is lost due to illegible and ill-maintained markers and in complete cemetery records (Byer and Mundell 2003).

ONCE PEACEFUL KILGORE CEMETERY LIES IN RUINS

“Shards of broken wine bottles, beer cans, and fast-food wrappers litter the Matthew Kilgore Cemetery. Knocked from their pedestals, monuments to early Sacramento pioneers lie cracked and fractured in the growing weeds that overpower scattered clumps of narcissus. Nearby the fallen pillar that marks the remains of German immigrant William Deterding and his family, half of a flat stone marker is missing, concealing the identity of the deceased from all but friends and relatives. Established in 1874, the Kilgore Cemetery today is in ruins. Located on Kilgore Road near Folsom Boulevard, it was once a peaceful resting place. But no more, “You take your life in your own hands when you go out there at night,” said George Yost, a neighbor who patrols the cemetery a couple of times a day. As a privately owned cemetery, the responsibility for upkeep of its 245 graves rests with the owner and descendants of those buried there. The cemetery was originally part of a 154-acre farm owned by Matthew Kilgore, a native of Ohio who left the Midwest and settled in Sacramento in 1855. According to records in the Sacramento County assessor's office, William L. Moore of Santa Cruz deeded the cemetery to Funeral Consultants Inc. in January 1983. Howard Keene, a spokesman for Funeral Consultants, which has a post office box in Fair Oaks, said the cemetery is still owned by Moore because he filed for bankruptcy soon after granting the deed. Moore was unavailable for comment. Some relatives of those buried in the cemetery live nearby, and 35 are active in the Matthew Kilgore Cemetery Association. Association members say they have not abandoned it but are losing a long battle with vandals. “It's just truly a mess right now,” said Betty Kennedy, secretary-treasurer of the association. “We are not a bit proud of it, but there isn't much we can do about it. They tore down the gate and the fence with barbed-wire topping, and they just vandalized it, so it is just one big mess. People even came in to cut down eucalyptus trees for wood,” Kennedy added. Kennedy said her ancestors, back to her great-grandparents, are buried in Kilgore Cemetery. Several years ago, vandals dug up the grave of her grandfather and stole his skull. Kennedy said she does not plan to be buried in the three-acre cemetery because of the vandalism. Yost, president of the association, said about a quarter of those buried in the Kilgore Cemetery were relatives. Despite the vandalism, he said he still plans to be buried in the family plot. The headstone that marked the grave of his sister, who died as a teenager, was stolen, Yost said. Relatives have installed flat headstones in place of the 9-foot-tall white granite pillar marking the graves of George and John Ney that vandals destroyed. The Neys were his grandmother's uncles, Yost said. He said relatives also have covered the tops of graves with concrete to prevent vandals from digging up the bodies. In the spring, volunteer organizations try to spruce up the yard, cutting away the weeds, removing trash and fallen branches. But the occasional cleanup is not enough, Yost said. “We try to clean it up once a year, but it's in awful bad shape and the vandalism is very bad out there,” Yost said. “It's pretty heartbreaking to see it vandalized like that. “Although vandals are liable for damages and can be sentenced to up to a year imprisonment for maliciously vandalizing cemetery property, they are not often caught or prosecuted. “I can't remember anyone ever being arrested for vandalizing a cemetery in my career,” said Lt. Gil Magness of the Sacramento County Sheriff's Department. “Usually we find out after the fact, when the caretakers or families go out the next morning.”

[Sacramento Bee, Tuesday, March 13, 1984. Submitted by Kathie Kloss Marynik]

Figure 6: Images from the Matthew Kilgore Cemetery

In general regulation on the maintenance, containment or historic preservation of cemeteries did not exist in the United States until the passage of the National Historic Preservation act in 1966. This resulted in a vast number of cemeteries becoming categorized as archaeological sites (Tyler 2000). However cemeteries are not considered appropriate for designation on the National Register of Historic Places unless the cemetery itself represent a historicartifactual piece of landscape or particular site (Tyler 2000:95). In the United States regulatory requirement of cemeteries has been relinquished to individual States prior to the passage of National Historic preservation act in 1966, In California (Act to Protect the bodies of Deceased Persons Public graves 1854). State laws legislation of cemetery laws began prior to the 1930's in California.

Burial grounds within the United States are in various phases of use ranging from presently in use and well maintained, in some cases no longer visible and effectively “lost” to the historical record of the modern world. In California as well as the United States and other parts of the world, remains of departed and their places are important. When physical artifacts are at risk of being changed, stolen or even destroyed, these unique cultural resources should be recorded for the future by careful documentation. Frequently Documentation of Cemeteries is incomplete or non -existent, as this case

Methods

Historical primary research documents of the cemetery’s history, its landscape, and its artifacts. Historical research and ancillary data collection investigates a variety of sources of data. To the greatest extent possible, all historical information obtained regarding the cemetery and the individuals interred were attempted to be added to the spatial data as part of my census. This historical data was obtained using standard historical resource methods by means of libraries, databases, maps and historical archives would all be obtained as necessary to fill the gap for the cemetery property. In research based premises this would be called ancillary data that fill in list of information before pre-survey of the cemetery takes place.

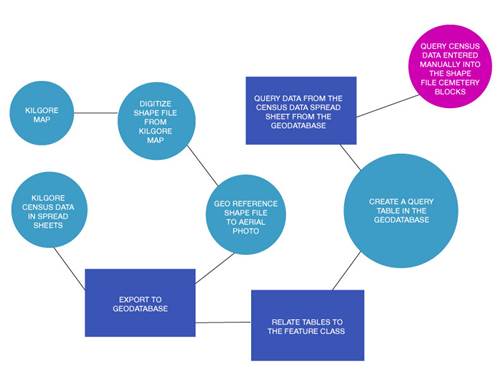

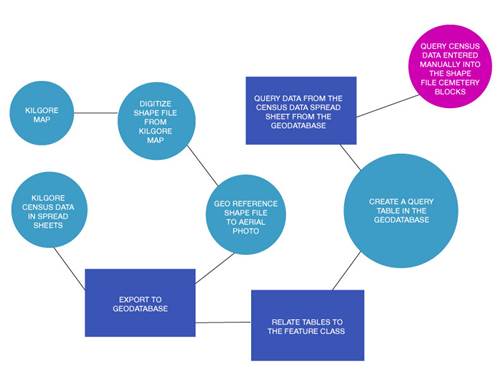

Figure 7: Project work flow

After having decided on my study area, the next step was to acquire historical data. The Center of Sacramento History houses an extensive collection of archive material and physical objects, including a collection of historic maps from Sacramento County area. With the help of Betty A, center archivists did a thorough and exhaustive process of searching a through number of photographs from the Eugene Heppting Collection and I settled on two, Burial Index by Billy Harris (1981) and Dorthy Bayless and M. Georgeanne Mello (1982). Though Harris lectured all about his book that he published the work of BayLess and Mello has been largely ignored. With the help of Betty, it was suggested that I contact the City of Rancho Cordova, given that the City had just acquired the Cemetery and was in process of fully restoring. With the help of friend, whose was a graduate student intern at State Parks and Betty Archivist, it suggested that I try to locate an original cemetery map from the Sacramento Valley Medical Society Museum to check to see if they additional cemetery records or cemetery maps.

First Map was an original map produced sometime around the 1920s that depicted the cemetery layout in a horse shoe shaped pattern with a majority of the cemetery lots laid out in twenty square feet shape with width of the graves three feet 4 inches for the width with width of sidewalks in between square blocks at four feet space in between them. The map was at scale of twenty links to one inch and where one link equal seven point nine two inches and included early directional location of information as to its location as in addition from notes to the original length of previous cemetery which now contains Folsom-Cordova Unified School District Continuation High-School precise location as next to National Registered Land Mark of American River Grange Hall in Rancho Cordova.

However, one apparent limitation with this map and modern one which was done up by the City of Rancho Cordova, is with this map there did not appear to be any matching modern day features to gravestone markers that are currently still located in the cemetery map of the area, as the City of Rancho Cordova facility manager and GIS administrator had noted to me. Most of the old grave markers were stolen, broken or taken by family to prevent further vandalism or in some cases, replaced by historic families in their plots or randomly placed in the cemetery as part of a beautification project of restoring the cemetery. So this closed the avenue of limitation of recording modern epitaphs and Monument measurements.

After the background research, surface reconnaissance was conducted in the cemetery to locate the presence of remaining graves that still contained transcribed information on the monuments. This would be accomplished by slowly walking through the cemetery, searching available markers that were still visible. Occasionally, this resulted in locating new graves markers in the twenty foot square context of the blocks in the cemetery, also confirming what city maintenance manager said, as well that many of stone had been discarded, stolen or replaced by modern markers.

Only those burial markers that retained original provenience and information were included in this study and if they supported by any background research as well new stone belonging in family plots in this study, few markers contained enough information that corrected background research as to confirmation restore to original block location for the study.

After determining the presence of burials from burials lists that were compiled from the record search, and a cemetery walk survey, it was determined that most commonality from all the records, in each block and row groups was most commonality among available information available for the study. As for the set data to be used in this Census would come to come down to the number of individuals broken down by gender categories of male, female Not applicable followed by age of death at death previous gender based categories and rate of burial of number of individuals with their age over time finally the number of known individuals occupying burial block. Description epitaphs and measurements would have to be left of this study in the because of terrible record keeping in cemetery and most markers were redone with modern epithets as part of cemetery restoration project.

The first step in preparation for digitizing the Kilgore cemetery map was to scan the paper map provided by the cities facilities manager on large format cannon document printer it at 600 dots per square inch, the highest resolution possible without having to use specialized printer for blue prints. The quality of image in the document became preserved in its regional entirety. I was however able to explore the scanned map at higher magnification value to decipher additional names and location and text, that would not have been readily available without scanning the map and additional inquires of more names became more available. As they were at time somewhat ambiguous given that they were written in pencil and some illegible cursive penmanship.

The next method begun was starting in arc map as edit session of digitizing the map using a heads-up digitizing method, rubber-sheeting the image of 103 burial blocks in place, using USGS digital raster graphic which was already scanned aerial photo had been geo-referenced to set off know ground control points between the map and aerial image as the best basis for effective means of better location of correspondence between the image and the now digitized rubber sheet blocks to image.

Figure 8: 1929 Map of the Matthew Kilgore Cemetery

That next step creation of query table was justifiable way query raw data from tables generated from Microsoft Excel Spread sheets which would be exported into feature database as collection raw numbers of individual in cemetery blocks broken down by Name of individual, there Gender, age at death and number of purported individuals occupying each cemetery block. Was justifiable way of collecting data and entering raw number in digitized shape file symbolizing the data from the collected census provide some form of spatial patterning as well way to provide statistical information of the census being conducted for the Matthew Kilgore Cemetery.

Figure 9: example of query table creation In Arc tool box under Data management sub routine function

Figure 10: Kilgore Pivot Table

RESULTS

Figure 11: Number Occupancy

The resulting analysis shows that number of People occupying Burial Blocks in Kilgore cemetery is on average between one to four Know Individuals with Block H15 occupying between 13-17 individuals, this would have been attributed to burial relocation from Kinney School Yard to Current Kilgore Cemetery location. Block H17 contains the family remains of Kilgore Family and Bradley Family in Cemetery.

The Bright red light color represent 0 zero occupation in the blocks running the color

1-4 occupancy

5-7 occupancy

8-12 occupancy

The Dark Color represents 13-17 people occupying cemetery blocks and most densely occupied blocks.

This is the result from using five unique classes of colors.

Figure 12: Number of Males

In this next map we see that number of Males occupying burial Blocks Is the Most densely occupied in Blocks H9 and H15 with between seven to ten males buried in these burial blocks

Color Scheme is Still Bright Red Light Color representing zero to The Dark Color 8-10

0 occupancy

1-3 occupancy

4-5 occupancy

6-7 occupancy

8-10 occupancy

Figure 13: Number of women

Color Scheme is Still Bright Red Light Color representing Zero to The Dark Color 7-8 people. Five classes

0 people

1-2 people

3-4 people

5-6 people

7-8 people

Figure 14: Number of people over age 50

Color Scheme is Still Bright Red Light Color representing Zero to The Dark Color 10-14 people. Five classes

0 people

1-3 people

4-5 people

6-9 people

10-14 people

Figure 15: Number people under the Age of ten

Color Scheme is Still Bright Red Light Color representing Zero to The Dark Color 2-3 people for three classes of data

0 people

1 people

2-3 people

Figure 16: Number people Age 20-50

Color Scheme is Still Bright Red Light Color representing Zero to The Dark Color 2 people

0 people

1 people

2 people

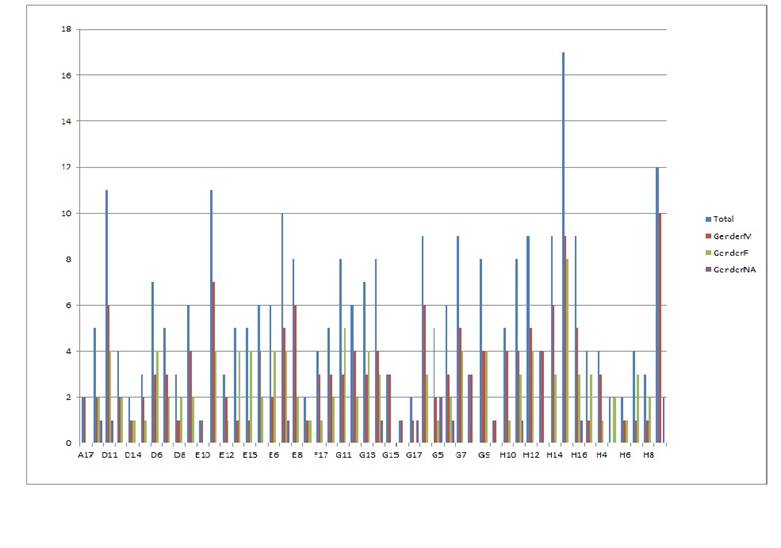

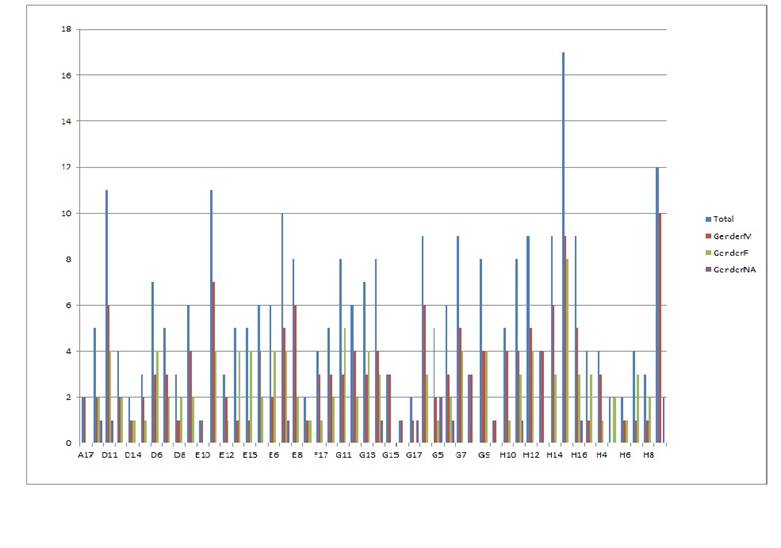

Figure 17: Number of Individuals by gender in assigned Burial Block Groups

Blue Bar: represents total number of people in burial Block groups

Red Bar: represent total number of Males in Burial Block groups

Green Bar: represents total number Females in Burial Block groups

Purple Bar: represents total number of non -assigned to Gender category in burial Block group.

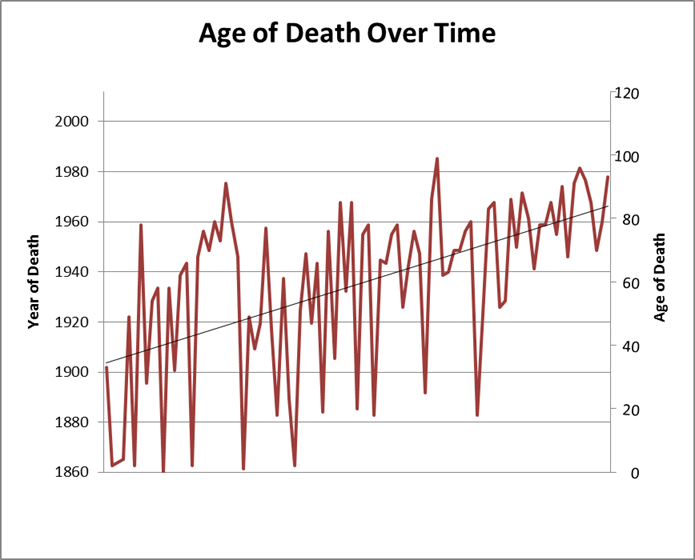

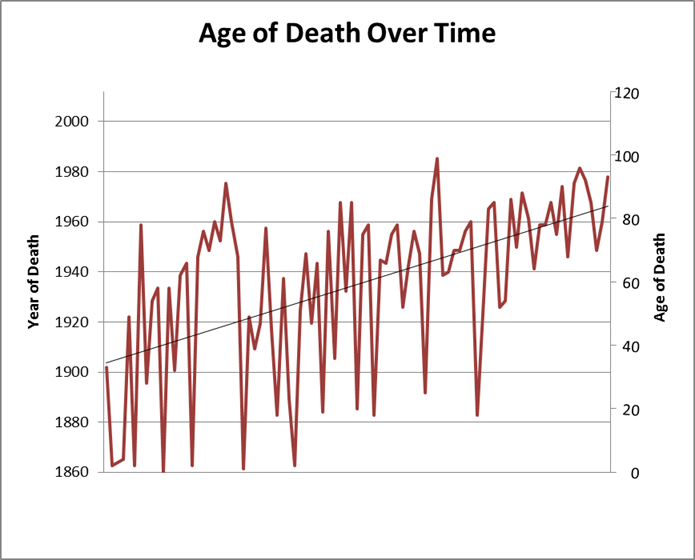

Figure 18:

Represents the total number of women over time and there ages at which they passed away.

Trend line indicating that numbers of women are living on average to early 80s

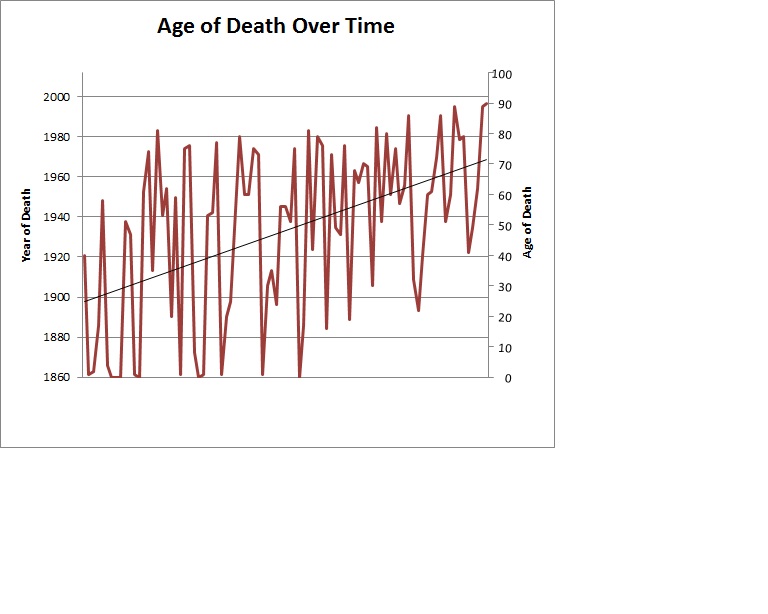

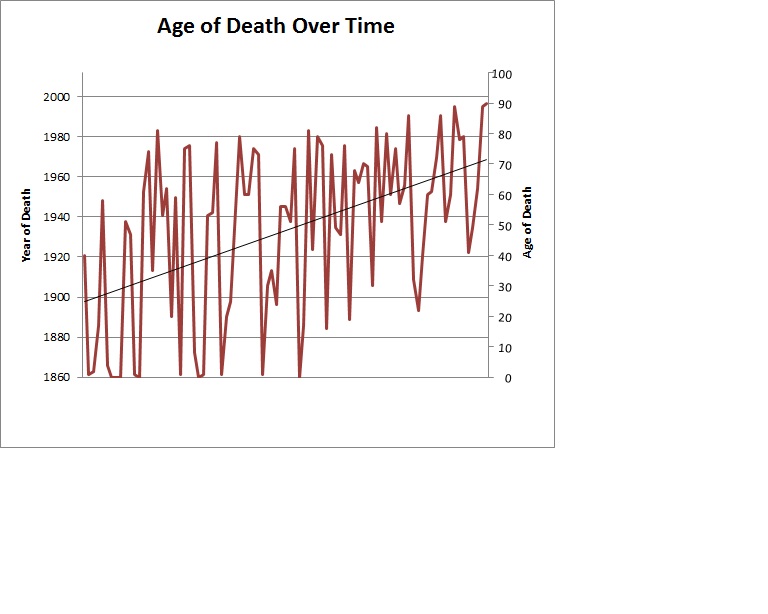

Figure 19:

Figure 19:

Represents the total number of men over time and there ages at which they passed away.

Trend line indicating that numbers of men are living on average to Early 70s

Analysis

This initial study gave me the confidence in modeling the census number and explaining the over changes and spatial patterns of internment into the cemetery of where oldest sections took place as well as changing dynamic trend longevity in the local community over hundred thirty three year history before in restoration in 2007. And also provided yet another additional avenue in exploration of cemetery analysis in California which largely not been explored in California archaeology.

Conclusion

Historical Cemeteries in California do provide insights into subjects not usually covered in archives and history books and current California archaeological topics. This initial foray in this topic of discussion and analysis not only the way sociological as well genealogical historical analysis that cemeteries offer to community in terms of analyzed subject such as census bearing data as whole change of historical community dynamics

The historical cemetery data from the Matthew Kilgore Cemetery indicates that neglected ill maintained cemeteries still offer assortment of data for analysis in exploring issues of death and population dynamics over time as well showing the extended lifespans in historical setting over time from late 19th century to 21 century in this hundred thirty six year old cemetery located in Rancho Cordova.

Work Cited

Bayless, Dorthy. M., and Mello, Georgeann

1982 Rest In Peace Early Records From Cemeteries in the City and County of Sacramento. Sacramento: Dorthy Martin Bayless

Byer, Gregory B, and John A Mundell

2003 Use of Precision mapping and multiple geophysics methods at the historic Reese Cemetery in Muncie, Indiana. Paper read at Proceedings of the Symposium on the Application of Geophysics to Engineering and Environmental Problems, at Golden, Co.

Clarke, Keith C.

1997 Getting Started with Geographic Information Systems. Prentice Hall Series in Geographic Information Science. New Jersey: Simon & Schuester.

Dethlesfen, E.J. Deetz

1981 The Cemetery and Culture Change: Archaeological Focus and Ethnographic Perspective. In Modern Material Culture: The Archaeology of US. Edited by R. A. Gould and M.B. Schiffer, pp. 137-159. Academic Press, New York.

Dethlesfen, E. and J. Deetz

1966 Death’s Heads, Cherubs, and Willow Trees: Experimental Archaeology in Colonial Cemeteries. American Antiquity 31(4) 502-510.

Duceker, K.J.

1979 “Land Resource information systems: a review of fifteen years experience

Geoprocessing, vol. 1, no.2, pp. 105-128.

Forbes, H.

1927 Gravestones of Early New England and the Men Who Made Them, 1653- 1800. Houghton Mifflin, Boston Massachusetts.

Harris, B.

1981 Sacramento County Cemeteries. Cook & McDowell Publications

Ludwig, A. I.

1966 Images: New England Stonecarving and its Symbols, 1650-1815. Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, Connectitcut.

Marynik, Kathie Kloss

1984 ONCE PEACEFUL KILGORE CEMETERY LIES IN RUINS. Sacramento Bee 13 March.

State of California Senate and Assembly

1854. An Act to Protect the Bodies of Deceased Person and Public Grave Yards.

Tyler, Norman

2000 Historic Preservation: An Introduction to its History:, Principles and Practice. New York: W.W. Norton and Company

Additional Links

Center of Sacramento History

http://www.cityofsacramento.org/ccl/history/

Old City Cemetery Committee, Inc.. Sacramento, California

http://www.oldcitycemetery.com/

Evergreen Cemetery Fayetteville, Arkansas

http://projectpast.org/gvogel/Evergreen/Evergreen.html

Dethlesfen, E. J. Deetz

Death’s Heads, Cherubs, and Willow Trees: Experimental Archaeology in Colonial Cemeteries. American Antiquity

https://www.udel.edu/anthro/neitzel/deathheads.pdf

Figure 19:

Figure 19: