Title

Mountain Lion Sightings in Central California

Author Information

Shawna Veach

American River College, Geography 350: Data Acquisition in GIS; Fall 2012

Abstract

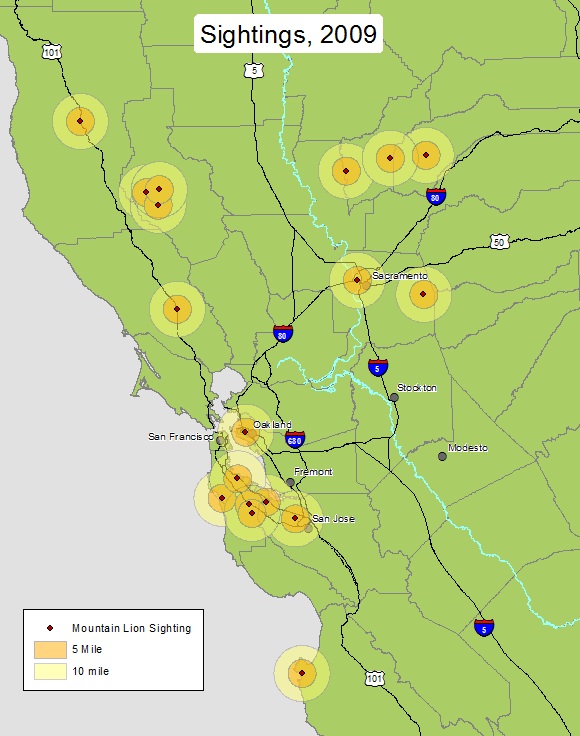

This paper is a brief summary of mountain lions, their general nature and habitat, as well as an over view of studies that have involved them. The meat of this paper is a map that was created from a source of mountain lion sightings in the Northern California/Central Valley/Bay Area. These sightings were originally in a list form, but have much more power when in a visual map form.

Introduction

Throughout California mountain lions have been sighted, while usually not becoming a problem. With human development, around the central valley these sightings have become more frequent. In years past hunting of the lions was legal and encouraged to keep their population down, to keep them from

attacking livestock, pets and even humans. Today however law regulates the situations where killing a mountain lion is appropriate and the steps following that need to be taken. Many people around the Sacramento area have used the American River Trail and at least once a year there is a sighting and hopefully it stays as just a sighting. Mountain lions usually feed upon deer and rabbits, but when their season slows and the population of lions is still high they will find outer sources of food. But from these sightings, or misfortunes, the mountain lion will really only travel so many miles from its home. This range may change on a yearly basis, but if there is more than one indecent it may have very well been the same lion. What this paper hopes to show is the sightings and possible ranges of mountain lions around central California and the Bay Area.

Background

The mountain lion, or Puma concolor, is known to be a fairly transient mammal (Pierce and Bleich). While the females can travel together, they are more likely to be found together during estrus; otherwise living a fairly solitary life. At one point in recent history, their range covered most of North America as well as through Central America, into South America. Only leaving those areas too close to the coast and those high elevation areas that were too cold for their pray to live, unoccupied. Needless to say as the continents were settled and developed the need to control the mountain lion population increased. Hunts were needed to keep them from killing farm animals; bounties were introduced to entice people to hunt. As of today, the mountain lion has been hunted down to a population west of the Rocky Mountains and a small patch in Florida.

Mountain lions are considered large carnivores, much like wolves and bears; however public views of the animals are much different (Kellert et.al., 1996). Often times attacks and sightings are over looked. While the authors do not draw any conclusions as to why this is, they do make a note of this trend not only in our current day, but mountain lions do not play a big role in Native American stories or traditional European stories. Over all this shows a lack of concern among the population and may would lead people to think that mountain lions are nothing to worry about, when in fact they are rather dangerous predators under the right circumstances.

The article by Mansfield and Torres is a brief summary of the way mountain lion predation has been dealt with by the Department of Fish and Game. Initially, the mountain lion concern was for livestock property, domesticated animals, and those animals that hunters valued. This caused for permits to be issued for the taking of mountain lions as a game animal. As of today, the mountain lion is classified as a protected animal and steps need to be followed before the animal can be killed(1994). However, with this legislation and our ever growing human population, the interaction between our two species is increasing. There have been more sightings in recent years than in previous, as well as, actual attacks. Needless to say, the authors conclude that some balance needs to be found between our two species; where they can exist at a reasonable level, as well as, not interfere with our never ending desire to expand (Mansfield and Torres, 1994)

A few case studies were found involving mountian lions and their presence or absence. Beier's 1996 discussion of mountain lions, or cougars as he chooses to call them, is a report of a 5.5 year survey of their population in Southern California's Santa Ana and Santa Monica Mountain Ranges. By creating models he predicts the possible outcomes of the animal's population if habit destruction continues combined with current estimated population values. His results were a to be expected, with less of the mountains available for mountain lion use and the destruction of the corridors between these two, the population will suffer. This also will increase the lightly hood of mountain lion sightings in the area, leading to another host of problems, like mountain lions using hiking trails for mobility purposes. Luckily this information was brought to the attention of law makers in 1991, putting mountain lions on the endangered species list; not allowing them to be hunted and their ranges a reserve area (Beier, 1996).

Another case study involving mountain lions was more focused on their predation of bighorn sheep in southern California (Wehausen, 1996). This study began after an attempted repopulation of bighorn sheep to the southern Sierra Nevada’s. With this population increase among the bighorn sheep, there was then an increase to the mountain lion population. The end result of the study was that the repopulation effort of the bighorned sheep ended up being for not because the mountain lion not only changed the migration pattern of the bighorned sheep, but also brought its population down to what it was prior to the repopulation effort. The authors concluded that prior to their next repopulation effort they must conduct more studies of the mountain lion population and other causes of their population fluctuation to have a more positive outcome for the bighorn sheep.

UC Berkeley headed a survey of riparian corridors in Sonoma County. This study was looking at what animals, if any, preferred the riparian corridor to the man made vineyard roads. While most of the animals were caught on their motion activated camera and evidence of were small game animals and domesticated animals; only a handful of survey excursions showed evidence of mountain lions. Those that did were the more cleared vineyard paths rather than the narrow or wide riparian corridors (Hilty and Merenlender, 2004). What this may show is a preference for mountain lions to man created pathways because clear areas give little option for their prey to hide; while the authors to not discuss any such conclusions.

Some news articles had also been found discussing mountain lions and their presence around communities; if they posed a threat. The only one of interest for me was a collection of sightings all over California for the year 2009. This became my source for data to use in this paper.

Methods

When looking for information on this topic, the first choice was a google search. Immediately results came back for sightings around the Sacramento area, as well as throughout the country. However with a search through google scholar and through the American River College library more results came up, but few results were specifically for the northern California region. Those articles that I felt were relevant were concerned about bighorn sheep, legislation having to do with mountain lions, some methodology for tracking and conserving predators, and their impact on safety as their habitat becomes smaller and smaller.

The most helpful was a general introduction to the mountain lion by Pierce and Bleich. They discuss morphology, range, and overall behavior. Kellert and others (1996) discuss the dynamics between large carnivores of all of North America and how humans interact with them. This was also helpful because the authors talked about how humans, in general view mountain lions and how this can vary across the nation in different areas depending on their contact with mountain lions. The other articles used in this paper may not have been intended for use in mountain lion research, but there was sufficient information for my uses.

Results

For my purposes, I created a map using ArcMap and ESRI's data that was made available to me through American River College. By using map layers to highlight an area of central California, showing higher population cities as well as mountain lion sightings; to then interpret from that what sorts of over laying spaces there are between humans and mountain lions.

Figures and maps

Analysis

The map shows the possible daily wondering of a mountain lion, but their locations are not surprising with what is known about mountain lions. However there are some flaws in the data. Only one source was easily obtained to create mountain lion sightings database; more could have been found and would have lent the dataset to being less biased towards the bay area and northern coast. It also would have been richer with more than just 2009 data. Also, the map has locations of cities, but not city extents; so locations of the sightings are general areas close to populations extents. This is also a limitation due to scaling, not so much the data’s fault. One last bias in the data that will lead to the conclusion, this dataset did not take into account sightings by Park Rangers, or any other worker in the Sierra Nevada’s, so it is unclear how out dense the mountain lion population is close to cities versus the wild.

Conclusion

So what can be learned from this paper? Well that it is best to be prepared to see a mountain lion at some point during a lifetime in California. They are all over this state and because of their transient nature, they can be found in some of the most unlikely of places. Remember to stay alert when hiking in more remote areas as well as to report any sightings to authorities, so maybe one day when some other student is trying to write a paper about them more data can be easily obtained.

References

Beier, Paul, 1996. Metapopulations Models, Tenacious tracking, and Cougar Conservation. Metapopulations and Wildlife Conservation, 293-323.

Hilty, Jodi A. and Adina M. Merenlender, 2004. Use of Riparian Corridors and Vineyards by Mammalian predators in Northern California. Conservation Biology, 18(1):126-135.

Kellert, Stephen R, Matthew Black, Colleen Reid Rush, and Allistair Bath, 1996. Human Culture and Large Carnivore Conservation in North America. Conservation Biology, 10(4):997-990.

Mansfield, Terry M. and Steven G. Torres, 1994. Trends in Mountain Lion Depredation and Public Safety Threats in California. Proceedings of the Sixteenth Vertebrate Pest Conference, paper 33:12-14.

Pierce, Becky M. and Vernon C. Bleich. Mountain Lion, Puma Concolor. Carnivores, 744-757.

Wehausen, John D., 1996. Effects of mountain lion predation on bighorn sheep in the Sierra Nevada and Granite Mountains of California. Wildlife Society Bulletin,, 24(3):471-479.

Photo Source

Dutcher, Jim and Jamie Dutcher. Mountain Lion, Felis concolor. National Geographic.

http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/mountain-lion/

Data Source

ESRI Data & Maps.

2009. Mountain lion sightings, summer/fall 2009, in Northern California. Over the line, Smokey! July 14, 2009. http://seesdifferent.wordpress.com/2009/07/14/mountain-lion-sightings-in-northern-california/