| Title Great Egrets in California's Central Valleys | |

|

Author Samantha Haynes American River College, Geography 350: Data Acquisition in GIS; Spring 2014, 2303 Glacier Pl Davis Ca 95616, (559)827-8349 | |

|

Abstract This project investigates the possible use of Great Egrets in California Valleys as an indicator of adequate riparian habitat. Tulare and Yolo counties are compared to determine if the agricultural crop differences contribute to the success of Great Egret populations. Further data and analysis is required to compare detailed crop information such as irrigation and seasonal differences between the counties. During the course of this project I have identified that there is a difference in the way Great Egrets use the different counties and will further investigate the many reasons why that is. | |

|

Introduction This project was intended to investigate the possibility of Great Egrets as an indicator species that could alert us to potentially successful riparian habitats, or as an initial indication of successful restoration efforts. I have personally observed a difference in the occurrences of the Great Egrets in relation to wetlands, various types of agriculture land, and the proximity of the agriculture land to riparian areas. Perhaps a specific level of riparian habitat is required to support reproduction, and agriculture fields may be supportive of the wildlife, but only if it is in a certain proximity to suitable riparian habitat? To further explore this question I began to compare California’s Yolo County and Tulare County. | |

|

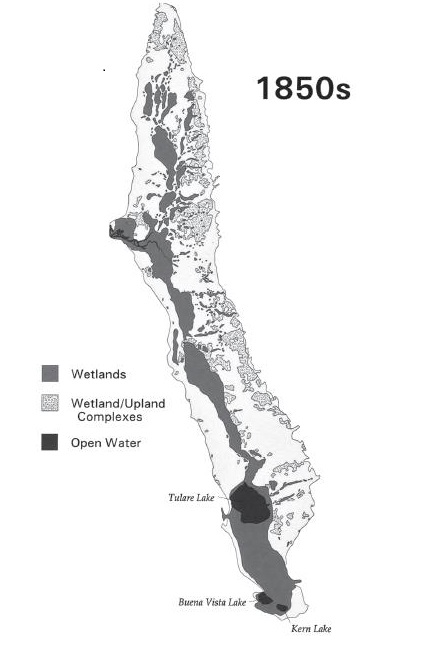

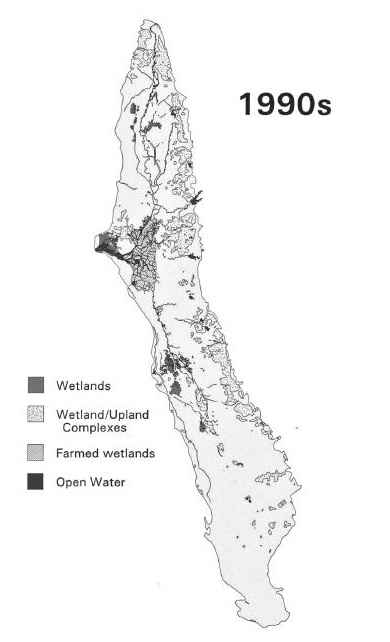

Background I was most interested in Tulare county and Yolo county because of my experiences living in each of these areas in rural and urban landscapes. I have noticed similarities and differences about the two regions. I feel that at the core they are very similar, yet they are very different. Growing up in Tulare County a vague history of the central valley was discussed. The native americans that previously lived there used reeds to make boats and ground acorns. The world of Tule ponds and streams and the need for boats seemed foreign to our local landscape and I imagined that these native Indians were living in another land or region of California. It wasn’t until I saw modern looking development covered in water that it became apparent that we had drastically altered the land and was why I could not imagine our home area as a wetlands complex. The first images I saw were published in a local calendar and contained flooding events and the local main street in Visalia fom 1906 covered in water and more from 1945. The southern portion of the valley in which Tulare County is located used to be home to a broad network of rivers including the Kings, Kaweah, Tule, and Kern River. These rivers had no natural outlet to the ocean and drained into several lakes including Tulare, Buena Vista, and Kern (Garone 2011). This landscape is no longer present. It has been continuously changed by being dammed and drained and in the process destroying millions of acres of wetlands. “The Tulare Basin was drained piecemeal, beginning in the 1850s with small scale irrigation projects along the rivers- especially the Kings, Kaweah, ant Tule- that fed the Tulare Lake. From a historic maximum area of 760 square miles an a maximum depth approaching forty feet, Tulare Lake today is entirely gone, and it’s bed and the basin’s former tule marshes have been converted to agriculture. (Garone 2011) The first time I came through the Sacramento valley was in the fall. The rice fields were flooded. I was driving along highway 99, all the fields seemed normal and familiar, except I kept asking “Why is there water everywhere?” The valley still felt very agriculturally centered and driven but I soon discovered that there was a lot more life in the region. The main thing I noticed was that almost everywhere there was more water; river, lakes, parks, ag fields. This area of the valley is closer to the delta and as you approach the delta there is less area drained compared to the extent than the Tulare basin was. There are more available spaces to reach the rivers and it seems to bring a culture as people gather here, use the resources, and appreciate them. I soon recognized that I commonly would see wading water birds, specifically the Great Egret along drainage canals, even near dry fields, and in fields far away from any substantial creek or water source that I knew of. In Tulare county I have seen Great Egrets, but not in the same reliable populations. I wanted to investigate the types of agriculture fields present in each county and the differences between the available wetlands and crop types in each county. I estimate that fields and many crops may provide sufficient foraging area and cover for these large birds, but that alone may not be enough if there is not a larger wetland habitat available for them nearby and sufficient trees to provide them with roosting sites and nesting habitat. I think the most important aspect to research is the distance the riparian habitats are from certain sites, to determine the connectivity of the habitat. The habitat that they require can be found in a large variety of land types across the world. They require freshwater, marine, or brackish water that is belly deep of shallower. They usually nest in trees over water up to 100 feet. They require cover on the ground in brush and bushes and trees. The available trees and cover are especially important during the migration during the wintertime and during the breeding season. Foraging can take place in a variety of locations such as streams, rivers, flooded agriculture fields, upland habitat, lagoons, and tidal regions. They feed on amphibians, reptiles, fish, crayfish, prawns, worms, isopods, dragonflies, beetles and grasshoppers (Chapman1984). Populations of the Great Egret declined when they were hunted for their breeding plumes until 1910 during the era of market hunting. They have also suffered due to habitat loss, degradation, and runoff from agricultural fields and sewage. Despite the unpleasant circumstances the populations have remain stable. They are the more adaptable than other Herons and Egrets and are the first species to arrive in the wetlands during the wintering season. Their arrival in a location may induce other species to arrive and use the habitat (Chapman 1984). It would seem that Great Egrets are an indicator to other species that the habitat is good enough quality to use. I was interested in investigating the ability of the Great Egret to be used as an indicator species that could alert us to potentially successful riparian habitats, or as an initial indication of successful restoration efforts. | |

| Flooded Tulare County 1906 |

| California Wetlands 1850s Garone (2011) |

|

California Wetlands 1990s Garone (2011) |

|

|

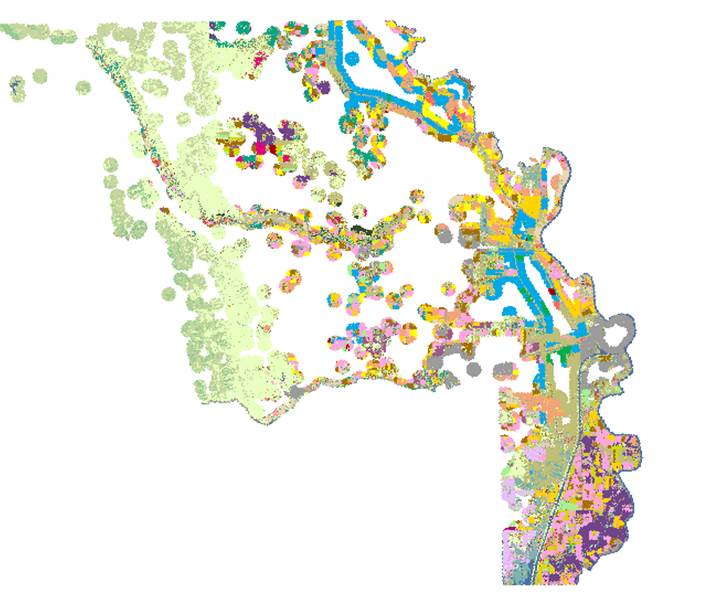

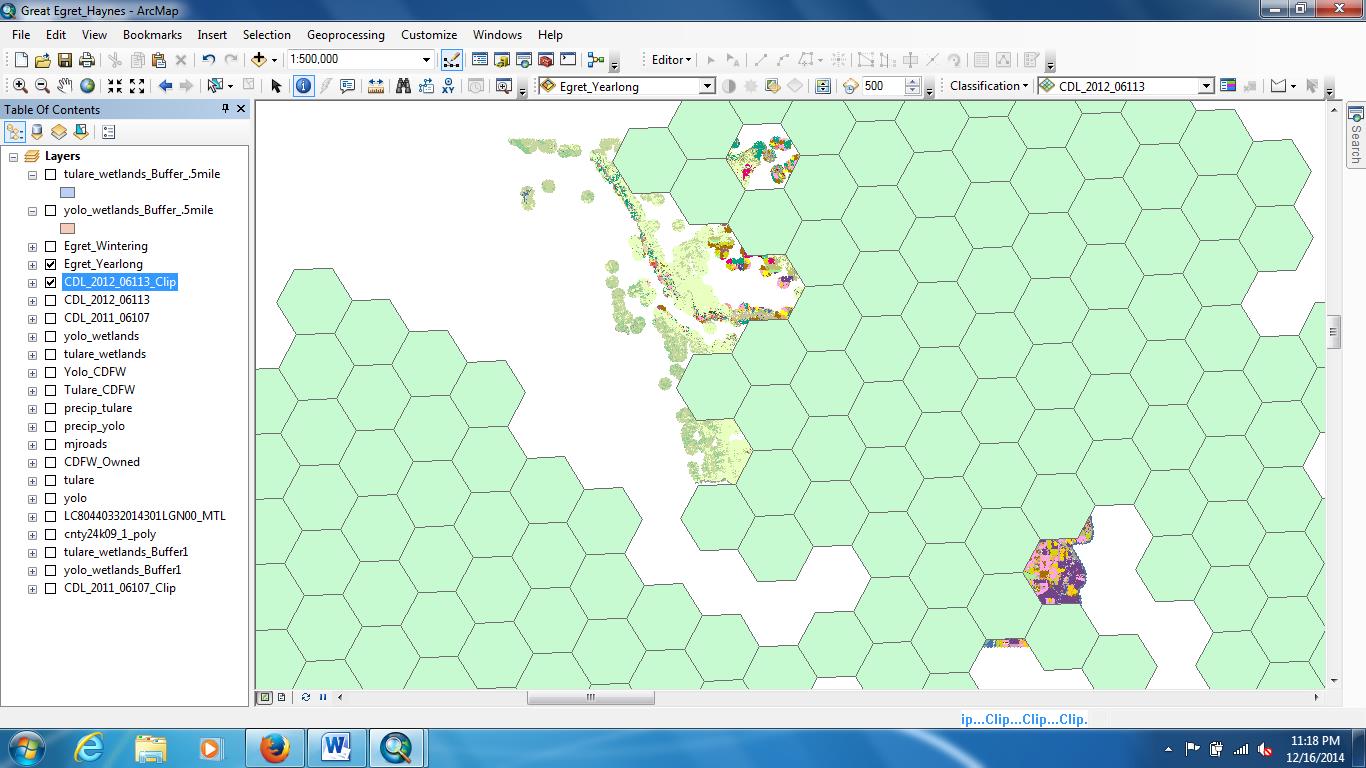

Methods I obtained Landsat 8 imagery from USGS Earth Explorer from Oct 28, 2014 for a segment of Northern California. I used a polygon of Yolo County obtained from Calatlas to clip the image to the extent and geometry of Yolo County. I also obtained Landsat imagery for an area of central California and used the same process to clip the image to Tulare County. I hoped to be able to classify the land types on the raster image, but realized that was too complex for my current skill level. I instead found a dataset that details agriculture crops and contained information regarding the type of crop, seasonality, irrigation type and much more. I used the same county polygons and clipped down to the extent of each county to ease the burden and time of processing. I added a layer from Calatlas from Department of Fish and Wildlife that contained information on bird species. I made a selection of only the great Egrets and exported that to its own layer. I made a selection on year-long and another on wintering ranges and exported each into its own layer file for later use during analysis. I added a wetlands layer also obtained from CalAtlas and wanted to draw a buffer around it and then determine what types of agriculture land were within the buffer. | |

| I decided how large to make the buffer zone by researching the range Great Egrets will travel during foraging, but failed to find information. I decided to make a 1 mile buffer around the wetlands, but decided that was too large to use with the data that I had since there were extremely small wetland areas. I reduced the buffer size to .5 mile and that was more reasonable to work with. You could still clearly see the contour of the rivers without a majority of the map being within the buffer area. |

|

|

Results I was unable to get clear results, but have begun researching what could be a very detailed topic. I encountered issues when clipping my Tulare County agriculture raster dataset with the .5 mile buffer of the wetlands. I was hoping to gain a clear picture of what crop types are within the buffer zone and compare the percentages with Yolo County. There are many aspects available to compare between the regions such as the irrigation of the fields, timing of the crops, available roosting sites near both foraging crop sites and wetlands areas, soil quality, and more. | |

|

Figures and Maps | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

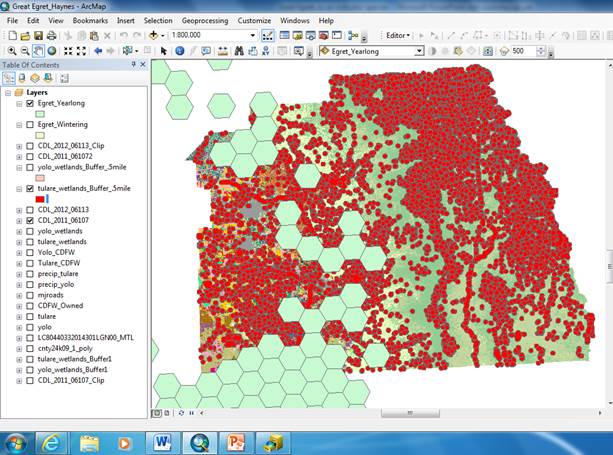

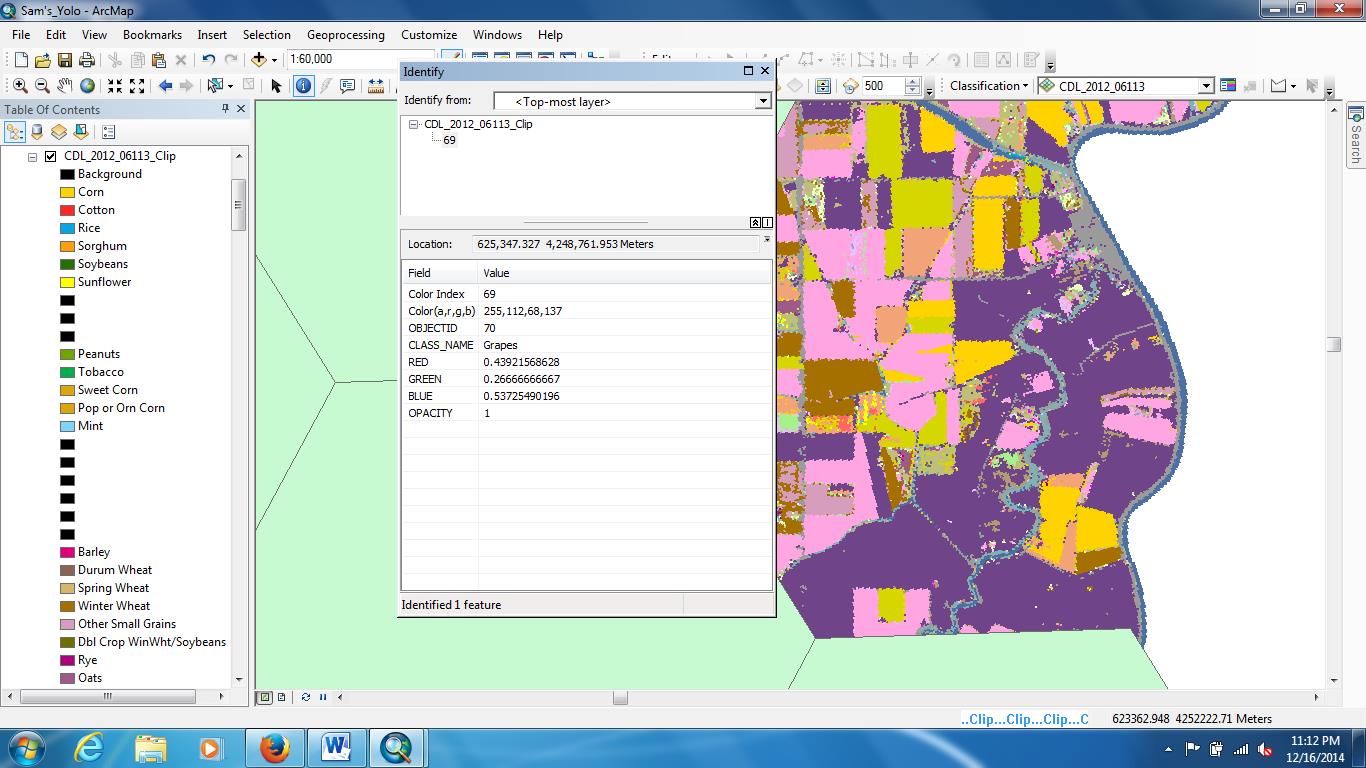

Analysis I continued my analysis of Yolo County very vaguely while continually trying to clip the Tulare County image. I overlaid the Great Egret dataset over Yolo County and found that most of the county was being used yearlong. There was an obvious vacant spot with no egrets yearlong.

I zoomed in and identified to see that it is a primary spot in which grapes are grown and there are few other places in Yolo County with that same classification. When the yearlong and wintering egret layers were applied, the entire area of Yolo County was covered. The entire area of Yolo County houses Great Egrets at least a portion of the year. I compared this to the Great Egret range over Tulare County as a whole and it was clear that there was less usage all year long. There was a fair amount of coverage during the wintertime, but I am speculative of the accuracy of the data since I do not know how many birds are present or if it is only information on its presence/absence. There was clearly a large portion of wetlands in Tulare County that were never used by the Great Egrets. It was classified as Evergreen Forest, so that lack of birds there is a result I would expect. In Yolo County I had some holes in my clipped data. I added the Egret layer and found no data beneath some areas of usage. These would be areas over .5 miles from a wetland area. It would be useful to know this data especially because it would tell us which crops the birds are willing to travel the furthest from wetlands to use. Additionally if there is land use by the birds where we do not expect it there may be potential resources or prospective habitat that it unknown. | |

|

Conclusions May be difficult with short time to determine all of the crop types within the buffers that are used because there are many very small areas classifies as wetlands with very varying land types directly surrounding them. I found it easier with the time constraints to focus on the crop types that are least used even when they are near wetland areas. Perhaps these crops do not support a certain aspect of the birds life history, or perhaps it is only when it is a large area of one crop such as the grapes that limits the ability to obtain all that it requires within a short distance. It would be interesting to further investigate how large a mono-crop area would need to be before it is detrimental to the wildlife, restricting them from being able to easily access multiple resources. I believe these birds may be able to exist in denser populations in the Central Valley as long as there are varying resources available to satisfy all their needs. Maybe it is not the type of crop that keeps them there only in winter but the point at which the crop is in the winter, irrigated, fruiting, etc. This would need to be investigated for each crop type. I believe with more time and effort I could easily investigate each crop growing cycles and seasons. With all of this information together it could be combined to determine the best organization of agricultural fields and preserved wetlands to encourage a sustained connected ecosystem benefiting the wildlife and the needs of the people. | |

|

References Chapman, B., & Howard, R., 1984. Habitat suitability index models: Great Egret , Washington, D.C.: National Coastal Ecosystems Team, Division of Biological Services, Research and Development, Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Dept. of the Interior. Garone, P., 2011. The fall and rise of the wetlands of California's Great Central Valley. Berkeley: University of California Press. | |