Bridging the Divide With GIS: A Brief Exploration Into The Applications of Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Andrew Lozano

American River College, Geography 350: Data Acquisition in GIS; Fall 2015

Contact Information: Alozano@bargasconsulting.com

Abstract:

Advocates of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), a commutative body of knowledge, practice, and belief, evolving from adaptive processes and handed down through generations via cultural transmissions that focuses on the relationship of living beings with one another and their environment, have promoted its use in scientific research, resource management, and ecological understanding but to no avail in acceptance in the wider mainstream, western, worldview. However, a growing body of knowledge, case studies, and multifaceted research projects show that the benefit of its incorporation can not only compliment the western practices but also further the knowledge base of environmental function and human interaction. While difficulties remain in bridging the divide between western science and TEK, GIS may potentially provide the language in which the fusion of western practices and traditional ecological knowledge and techniques could lead to better managed resources, the preservation and resurgence of native culture, species diversity and richness, community level restoration efforts, adaptive management techniques, and a new paradigmatic outlook on the relation between ecosystem and human interaction.

http://americanindianshistory.blogspot.com/2012/05/houses-of-california-native-americans.html

Historic photo of California Native Americans

Introduction:

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), like Western science, is a dynamic and cumulative process that builds on practical experience, adaptation to change over time, and collective wisdom (Berkes et al, 2000). While there remain some critical differences between the two, the ultimate goals of both TEK and Western science are the sustainability of populations and the preservation of diversity within the context of economic needs and social harmony (Society for Ecological Restoration, 2015).

Conventional, or Western, resource management has come under criticism because it is equilibrium-based or has an underlying assumption of ecological stability (Berkes et al. 2000).

Furthermore, there is a seemingly stagnant perspective within ecological restoration projects and various resource management projects that any and all human interaction is detrimental and destructive of an ecosystem’s function, progress, and succession (Huntington, 2000). However, much of the landscape has been tended and managed by first nations for hundreds, potentially thousands, of years; ultimately shaping areas of which are thought to be historically undisrupted, with high success rates of diversity, stable yields, and species density.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is a continuously growing field and is used in a wide array of applications. GIS already is and may be an important tool in the future for translating data, synthesizing data, analyzing, a means to educate and train, and coupling these two cumulative knowledge-based systems for betterment of first nation communities, local communities, and conservation / restorative efforts.

This document looks to identify avenues of further research in an exploratory effort to understand a potentially important fusion of western practices and traditional ecological knowledge and techniques that could lead to better managed sites, the preservation and resurgence of native culture, species diversity and richness, and a new paradigmatic outlook on the relation between ecosystem and human interaction.

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-4-Naaddjmos/UzMFj4qVnfI/AAAAAAAAWW8/WJw8jLmQ9fo/s1600/tmp.jpg

Background:

Traditional Ecological Knowledge is an attribute of societies with historical continuity in resource use practice. By and large, these are less technologically driven societies and nonindustrial, many but not all of them indigenous or tribal (Dei 1993, Williams and Baines 1993). For ecologists, TEK offers a means to improve research and also to improve resource management and environmental impact assessment (Huntington, 2000)

Example of a TEK derived of Bison Range in Yellowstone

http://atlasofyellowstone.com/slideshow/content/bison_range_large.html

Advocates of TEK have promoted its use in scientific research, impact assessment, and ecological understanding to varying levels of success. Case studies, such as those found in the published article, “ Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as adaptive management” point out that there exists a diversity of local or traditional practices for ecosystem management. However, wider applications of TEK derived information remain impalpable within the realm of western applied science and management within the U.S. From the documents found during research for this project there are several key points that must be addressed before Traditional Knowledge can be utilized as more than a token favor or a quasi-scientific information system.

Although a dramatic paradigm shift may not be on the horizon, a fruitful multifaceted approach remains hopeful as a small but growing number of U.S. federal agencies, state agencies, and non-government organizations have begun to see the value in incorporating traditional knowledge in management practices (Berkes et al, 2000). One may find the spear of bridging the divide in places like British Colombia where community level maps are emerging as a powerful medium to communicate local values and knowledge (Olive, Carruthers, 1998).

From Ecotrust Canada, a non-profit organization devising innovative approaches to conservation-based development in the costal temperate rainforest region of British Colombia, Canada, have been working on this paradigm thoroughly for several years. The mapping office within the NGO has been working with First Nations and community groups to build local capacity in mapping.

TEK and contemporary research, such as the brief case study within this document, show that the incorporation of traditional resource management techniques and community level mapping may help in long-term ecological sustainability efforts, biodiversity, ecological role/function of a site, community outreach, and cultural resurgence.

http://atlasofyellowstone.com/slideshow/content/indian_places_large.html

Methods:

Upon researching this topic and the various themes imbedded with the proposition of utilizing GIS as a catalyst in bridging the divide of TEK and western science this author arrived at the doorstep of realization that trust, disclosure, and agreements prevent, understandably so, the wide array of cultural knowledge and resources from being entirely open to the public.

Research was conducted using several research databases including the California State Library, Community library, and various credible online sources. Search terms utilized for gathering valuable data and information ranged but can be categorized and simplified to several keywords and themes such as: Native American lands, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Geographic Information Systems, and Traditional Use Studies.

Results:

The results of this study reside in the realm of successful cases studies, where implemented TEK has shown to produce positively correlated results and cooperation amongst facilitators and a small number of maps derived from an excelling organization called, Gitxsan Strategic Watershed Analysis Team, or SWAT, that resides in British Colombia.

SWAT is an early adapter and content creator that have produced maps and information that are culturally relevant and politically powerful. By integrating data collected from Global Positioning Systems (GPS), ground surveys, oral histories, and GIS models, the SWAT group and their affiliates have produced a series of available maps of biophysical and cultural values in their territory (Figure 1).

(Figure1) http://www.conservationgis.org/native/native2.html

(Figure1) http://www.conservationgis.org/native/native2.html

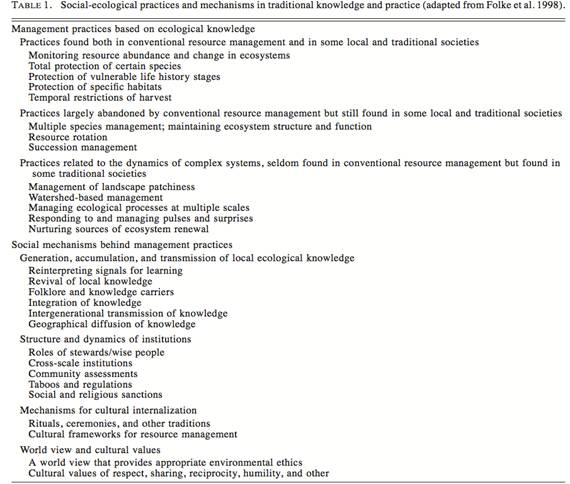

Berkes, Colding, and Folke present a well organized table in which they worked through practices which ecosystems and biological diversity is managed to secure a flow of natural resources and ecological services on which people depend:

1. Identify a selection of management practices based on local ecological knowledge.

2. Identify a number of social mechanisms behind these practices and organize them sequentially from the generation of knowledge, to the underlying worldview and values of the culture from which the knowledge is embedded.

3. Evaluate traditional knowledge systems for insights they provide for the qualitative management resources and ecosystems, and for parallels to adaptive management.

Ecotrust Canada, the NGO mentioned in the background section of this document, has structured a viable objectives model that assists in their research and implementation of TEK driven GIS databases:

1. To improve access to public information resources

2. To provide training and education in mapping and GIS for environmental analysis

3. To facilitate the inclusion of local and traditional knowledge into maps and GIS databases

4. To provide effective mapping products to support and lead conservation advocacy in B.C.

5. To strengthen community and regional networks in the use of GIS for conservation-based development.

There are some excellent examples of a TEK driven practices, many of which have been largely abandoned by conventional resource management but still found in some local and traditional societies. However, while many practices have fallen out of favor in government resource management, some are being rediscovered as reflected in the growing resurgence of agroecology, integrated farming and aquaculture, and polyculture (Berkes et al, 2000).

“A Nigerian case study identifies an agroforestry system combining food crops and domesticated trees as the oldest farming practice in the area. Since the beginning of the 20th century, this system has taken the form of a perennial mixed plantation that includes cash crops such as cocoa, oil palm, and coffee. Many multiple species management approaches result in soil fertility improvement and crop protection through the integration of trees, animals, and crops (Altieri, Nicholls 2004). For example, the Bisnois of the Thar desert of India maintain their resource base through managing a keystone process tree species, Prosopis cinerarea. This leguminous tree helps fix nitrogen and enrich the soil, creating ideal conditions for crops that are planted under the shade of these trees. The leaves provide fodder, branches provide fencing material and firewood, and pod are eaten by both cattle and humans.”

The use of fire as a ecological management tool is a great, and contemporary application of TEK, and shows the potential for TEK to influence changes in land management processes (Vinyeta, Lynn, 2013).

“Euro-Americans arrive in North America bearing their folk knowledge that held fire in forests to be destructive and hazardous to humans (Arno 1985, Lewis 1982). This view contrasted sharply with the traditional knowledge of the indigenous inhabitants, who embraces the benefits of burning and were skilled in application of fire technology (Kimmerer and Lake 2001: 36).”

Taking the lead in mapping TEK are GIS managers like Roman Frank, B.C., of Ahusaht First Nations GIS office. His work has helped to shift power in the community’s relationship with government and industry (Olive and Carruthers, 1998). Through his work with Wilcon Wildlife Consulting Ltd, Frank has mapped traditional and scientific data relating to Roosevelt Elk populations and critical habitat in Clayoquot Sound. These maps illustrate data that was collected using contemporary means such as transects, tracks and calling data based on interviews with First Nation elders, hunters, and local community members (Olive and Carruthers, 1998).

Analysis:

The widespread use, or lack there of, of Traditional Ecological Knowledge has not pushed forward yet in the United States beyond a type of token appreciation. There are patches of willing, interdisciplinary users in various NGO, Federal, and State agencies that are pulling TEK along in an effort to incorporate it’s knowledge base, and cooperation from first nations, in a scaled effort to research the potential of deep generational, and at times, intricate knowledge.

Some problem areas can be readily identified that must be addressed if there is ever to be widespread acceptance. Through analyzing various sources there appear to be several repetitive reasons that can be identified. Henry Huntington (Using TEK in science: Methods and Applications) addresses this issue eloquently and points out two factors that predominate:

“inertia and inflexibility. The former, inertia, is merely a general resistance to change because it upsets the familiar and comfortable. Working within an established paradigm is simpler than adapting to a new one. With continued pressure from advocates and holders of TEK, more collaborative research, and a growing mass of evidence from studies documenting and incorporating TEK, this resistance may be overcome. Inflexibility, on the other hand, is resistance specifically to TEK and the changes required by its use. It relies on more subtle arguments, questioning the reliability of TEK, or expressing concern about political correctness replacing scientific rigor. “

There are certainly more than two reasons for not implementing more TEK resources, many wildlife researchers and managers are unfamiliar with social science methods or are comfortable doing cross cultural research. In order for one to fully realize the value of TEK and western science, one must reach beyond the scope of their specific discipline and undertake a transformation and straddle various worlds in a challenging multidisciplinary undertaking.

Furthermore, TEK holders may be reluctant to share information and cooperation. This issue reaches back through the years to the early formation of the country and it’s agencies, some of which were the reasons the first nations lost their lands and rights. Gaining trust and building a reputation must take place as part of this ramp up into utilizing TEK.

Ecotrust Canada may be a solid example and model for the process of building the relationships necessary and the skills to undertake the task. The growing momentum of their success and the emergence of maps at the community level can be attributed to three processes.

First, the governmental treaties with First Nations signed in 1998 required the burden of proof be on the First Nations. Traditional Use Studies, or TUS, were the primary tools to establish traditional territory rights (Olive, Carruthers, 1998). The Ministry of Forests, the government agency that directed and funded TUS, set the goal to promote the collecting and mapping of First Nations land use and occupancy. The main funding for the TUS program was from another government agency (Forest Renewal BC, no longer functioning), which secured funding from stumpage fees paid by the forest industry.

Second, the TUS program produced maps of First Nation territories and activities from various sources including oral histories from elders that had intricate geographical knowledge of the land. The oral history as well as archival research provided: traditional boundaries, traditional and current land occupation, spiritual places, trails and trading routes, camps, traditional resource distribution and variations, as well as resource use over time (Olive, Carruthers, 1998). These complex map layers provided an array of valuable data.

A legal battle between First Nations ensued whereby a Supreme Court overturn gave aboriginal rights back to First Nations after the initial 19th century colonial law. This decision gave oral histories on equal footing to written documentation as evidence in the court of law, a remarkable accomplishment for First Nations.

The third driving the mapping is the implantation of Land and Resource Management Plans, or LRMP’s. This was initiated through a response to confrontations in B.C. over clear-cutting and other forest industry issues (Olive, Carruthers, 1998). These LRMPs (and coordinating agency called Land Use Coordination Office, LUCO) are public, regional planning tables, where government, environmentalists, industry, communities, and First Nations arrive at a land use consensus and agreement. The core of these plans are GIS maps and LUCO retains the data (soil, geology, land cover, etc) (Olive, Carruthers, 1998)

Conclusion:

The multiphase scenario in B.C. has begun to show an emergence of community-based maps where TEK is a key component, not simply from legal requirement, but because the atmosphere was primed through the several occurrences of necessity, cooperation, and interest in complimenting western practices. The local B.C. communities have been garnering the knowledge and skills necessary to build GIS maps on a large scale. The First Nation groups, the process is generating a visual and digital representation of their oral histories, capturing traditional values and knowledge. Maps have become a powerful tool for bringing traditional knowledge into planning and complimenting western science ad bridging the gap between the western sciences and traditional knowledge

While the use of TEK is minimal, and many efforts are in the exploratory stage; there is a refreshed outlook on the subject, such as the USDA in depth research in Exploring the Role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Climate Initiatives and Traditional and Local Ecological Knowledge About Forest Biodiversity in the Pacific Northwest.

Climate change is a global phenomenon that may potentially have unprecedented consequences and effects on our species for generations to come, but the impacts will not be evenly distributed amongst the world’s populations. Indigenous groups are projected to be some of the more heavily impacted by climate change (Parrotta and Agnoletti, 2012).

Secretarial Order No. 3289, “Addressing the Impacts of Climate Change on America’s Water, Land, and Other Natural and Cultural Resources,” sets the stage as the U.S. Department of the Interior states that, “climate change may disproportionately affect tribes and their lands because they are heavily dependent on their natural resources for economic and cultural identity” (USDI 2010: 4).

With this precedent, the stage is set for federal agencies to potentially take the lead in developing a paradigm shift and worldview that encompasses relevant and pertinent data from sources both western and traditional in practice. With the body of TEK well documented, its implementation should be attainable, albeit difficult, as stated due to difficulties getting resource managers to relinquish an aged 20th century outlook on biological structure and ecological dynamics (Vinyeta and Lynn, 2013)

With more research and cooperation between NGOs, government, communities, First Nations, and skilled GIS users, there stands an excellent chance, and opportunity, to build lasting bonds and blended datasets in which Geographic Information Systems help transition the information into more readily used models and maps that will be used worldwide in collected effort to adapt to the coming climate changes.

Citations:

Altieri, M. A. 1994. Biodiversity and pest management in agroecosystems, Food Products Press, New York, New York, USA.

Arno, S.F. 1985. Ecological effects and management implications of Indian Fires, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment

Station: 302-303

Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. 2000. Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as Adapative Management. 10(5): 1251-1262

Charnley, S. A.; Fischer, P.; Jones, E. T. 2008. Traditional and Local Ecological Knowledge About Forest Biodiversity in the Pacific Northwest

Dei, G.J.S. 1993. Indigenous African Knowledge Systems: Local Traditions of Sustainable Forestry. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 14:28-41

Grossman, Z. 2008. Indigenous nations’ responses to climate change. American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 32(3): 5-27

Holling, C. S., F. Berkes, and C. Folke. 1998 Science, sustainability, and resource management. Pages 342-362

Huntington: H. P. 2000. Using Traditional Ecological Knowledge In Science: Methods and Applications. Ecological Applications 10(5) 1270-1274

Kimmerer, R.W.; Lake, F. 2001. The role of indigenous burning in land management. Journal of Forestry. 99(11): 36-41

Lake, F. 2007. Traditional ecological knowledge to develop and maintain fire regimes in Northwesstern California, Klamath-Siskiyou bioregion: management and restoration of culturally significant habitats.

Lewis, H.T. 1982 Fire technology and resource management in aboriginal North America and Australia.

Lewis, H. T., and T. A. Ferguson. 1998. Yards, corridors and mosaics: how to burn a boreal forest. Human Ecology 16: 57-77.

Olive ,C.; Carruthers. 1998 Putting TEK into Action: Mapping the Transition

Sankhala, K. 1993. Prospering from the desert. 18-22

Vinyeta, K., Lynn, K. Exploring the Role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Climate Change Initiatives.

Web Sources:

Society for Ecological Restoration: http://www.ser.org/iprn/traditional-ecological-knowledge/tek-western-science Last accessed: 2015.12.14

Convis, C. 2000. The Gitxsan Model: A vision for the Land and the People. http://www.conservationgis.org/native/native2.html last accessed: 2015. 12. 14

Aboriginal Mapping Network: http://nativemaps.org/taxonomy/term/162?page=72 Last Accessed: 2015.12.14.