GIS in

Archeological Applications From a Cultural Perspective

By

Der Hsien Chang

American River

College

Geography 350:

Data Acquisition in GIS; Fall 2016

Abstract

Artifact identification is paramount in

understanding a site and the human history that evolved from it. Archeological applications on a site using

GIS aids the archeologist in proper identification and interpretation of the

artifacts. In particular, Chinese

artifacts are sometimes mis-identified and mis-categorized due to the lack of

understanding of exactly what this artifact is and where on a vessel it comes

from. This paper will address in detail

how GIS is helpful in the archeological investigation process.

Introduction

One of the most important aspects of archeological

work is attempting to reconstruct the past by systematically removing and

recording layers of dirt, material culture, flora and fauna samples, and soil

content. In the past, the recordation

were mostly descriptive in nature. In

the instance of artifact identification and interpretation, there did not exist

a process to generate a 3 dimensional presentation of the artifact provenience

whereby these items could be mapped after their removal. This shortcoming had led to

mis-categorization and misunderstandings of Asian ceramics in the analysis process

thereby leading to inaccurate interpretations of the archeological site(s).

Background

Generally speaking, Asian historical artifact

compilation is not a topic taught in the archeological field work. The misidentification and mis-categorization

of Asian artifacts is often found in the archeological literature (Chang

2006). There did not exist a technique

to which ceramics could be mapped spatially in 3-D such that the tabular data

gathered in the field could be viewed alongside the spatial representation

until GIS. The GIS process captures the

snapshot of the artifact in its original location in the field prior to removal

to provide much more detailed information that would otherwise be lost or

shuffled away once the field work was completed. This paper discusses the

concept of using GIS to provide a more precise interpretation of the Chinese

ceramic assemblages in the context of an archeological site.

Figure

1 Kiln waster pieces from an

archeological site in Hong Kong

Methods

With the application of GIS (ArcMap), an archeologist

has the ability to have side by side a tabular descriptive and quantitative

report alongside a spatial representation of that information at their

disposal. This advancement in viewing data

from two different vantage points allows the archeologist to not only see in

3-D through the spatial side, but also conduct analyses through the tabular

side seeing each layer of material culture contained in specific recorded depths

of soil. This process explicitly sheds

light on human behaviours of the past.

Results

For a specific example, let’s turn to the widely

distributed “Four Seasons” pattern Chinese ceramics. This particular type is found in Oregon, Washington,

and California in mining sites, labors’ camp and in Chinese communities from the

1860’s and onward (see Chang 2006, Farncomb 1994, Felton et.al, 1984). The Four Seasons pattern tableware set is

unique in that there are at least 7 particular individual pieces within this

setting: wine cups (2 sizes), tea cup, small plate, large plate, soup bowl,

soup spoon, and serving bowl. This

specific motif tableware has been found at sites locally in Auburn, Loomis, and

Woodland in various tableware sets (see Farncomb 1996, Felton et.al.1984).

Figure

2 Excavated Chinese ceramics from Virginiatown

site

Analysis

The various arrangements of the Four Seasons tableware

set implies several kinds of possible settlements at that location: migrant

camp, temporary camp, community settlement. Each of these settlements are

different in terms of the purpose, the length in terms of time, and even

possibly the number of people in the group.

With just a description, a list showing minimum number

of units of sherds of ceramics or even just a count of the sherds does not

provide a visual representation of the artifacts in both their original

provenience prior to removal in the field nor provide a description that could

immediately visually correlate to the spatial data at hand (Felton et.al,

1984).

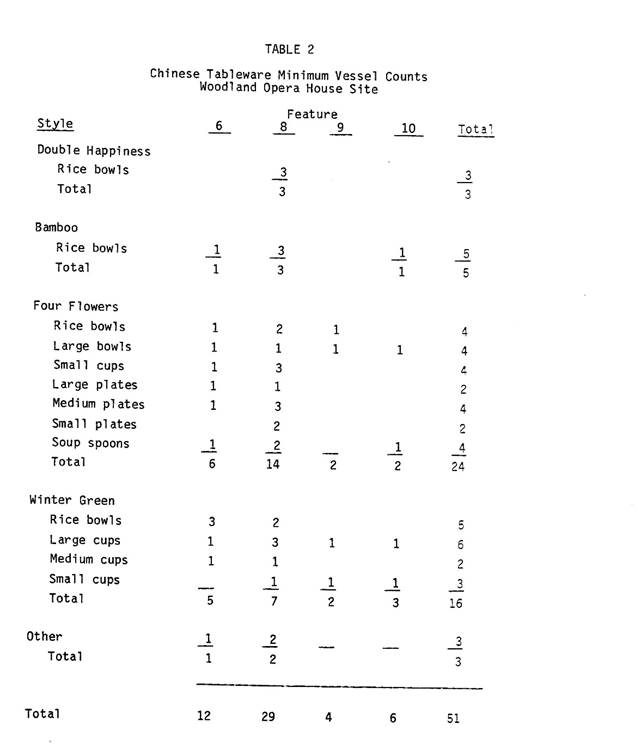

Figure

3 Woodland Opera House Ceramic Count

Presently with the same data noted above, utilizing

ArcMap and file geodatabases, it becomes a 3-D visual map with different layers

of dirt and within each layer, one can clearly see the ceramic sherds within

the dirt prior to removal. Clicking on

the individual layer on ArcMap, one can then bring up the tabular data that

corresponds to that specific layer of dirt.

This ability to view both a tabular data and a spatial data in one

screen makes it that much more easily to conduct analyses, comparisons, or

interpretations of the ceramics in question.

The various Four Seasons tableware sets are complicated to identify

especially when the pieces are small during excavation and brought back to the

lab for processing and categorizing. The

task of identifying the sherds and where on a piece of ceramic it belongs to

can be a daunting task if there are many pieces in a tableware set. However, with the mapping tools available in

GIS, one can clearly identify the layer that this piece was born from (spatial)

as well as know the exact description of that piece of ceramic such as the

body, the lip, or the base (tabular).

Conclusion

The concept presented in this paper is that using GIS

in archeology, especially in mapping ceramics, Chinese ceramics, commonly

distributed in archeological sites across California have simplified the

process in the identification and analysis phase of archeological work. Without the spatial representation of the

ceramic “in situ” and the tabular data corresponding to the layers of dirt, the

paper field documents really provide only a 2-D view of the static site. In the static view, information can be lost,

disconnected and even mis-interpreted.

GIS brings the archeological site into a visual perspective by

illustrating the layer by layer view of what is happening out in the

field. This is a powerful way to record,

view and convey data.

References

Chang, Der Hsien

2006 Ch’ing Dynasty Chinese Porcelains in California. M.A. Thesis.

Department of Anthropology, California State University, Sacramento.

Farncomb, Melissa K.

1994 Historical and Archeological Investigations

at Virginiatown: Features 2 and 4 M.A. Thesis.

Department of Anthropology, California State University, Sacramento.

Felton, David L., Frank Lortie, and Peter D. Schulz

1984

The Chinese Laundry on Second Street:

Archeological Investigations at the Woodland Opera House Site. California Archeological Reports No. 24.

Sacramento: California Department of Parks and Recreation.