| Title Ferruginous Pygmy-owl at the U.S.-Mexico Border | |

|

Author Janet Kruse American River College, Geography 350: Data Acquisition in GIS; Fall 2016 Contact Information (Carmichael, CA email: jek955zz@yahoo.com) | |

|

Abstract Border fences are political barriers built to control passage of people between two government states. Wildlife do not understand these artificial barriers that have nothing to do with natural ecological boundaries defining separate niches and habitats. This project considers the cactus ferruginous pygmy owl, whose habitat range crosses the border between Arizona and Mexico and the location of the current fencing and future fencing being considered today. This project is an attempt to quantify and visualize the effect of the fencing on individuals and hence, speculate the future abundance of these birds with the fencing in place. Maps were created to visualize the temporal change of the pygmy-owls range in the last 50 years and what types of structures, natural and man-made exist within the owls habitat. Studies were done ten to fifteen years ago to determine the effects, if any, of roads within the owl’s nesting area on the owl’s behavior. Conclusions were drawn that the roads had a determinate effect depending on distance from nests and other factors. When noise levels increase or width of the roads increases or the volume of traffic increases, the number of road crossings the owls make decrease. Comparing the roads in the owls’ habitat in Sonora, Mexico with border fencing of 15 feet tall or higher leads one to believe that owl behavior modification could magnify at the border barriers. Future studies need to be done to determine the impact of the abundance of species populations and how the ecology of the land will most likely also change. | |

|

Introduction Homeland Security was authorized in the 2000’s by President Bush to build a $2.2 billion wall in five sections along 700 miles of the 1954-mile-long (3,145 km) US-Mexican border. Arizona and its border with Mexico was chosen for this project due to the existing and possible future fencing along the entire Arizona-Mexico border. One planned section for the border fencing runs from Calexico, CA to Douglas, Arizona. Arizona ecosystems close to the Mexico border have unique and biodiversity wildlife and flora, some not found anywhere else in the world! | |

|

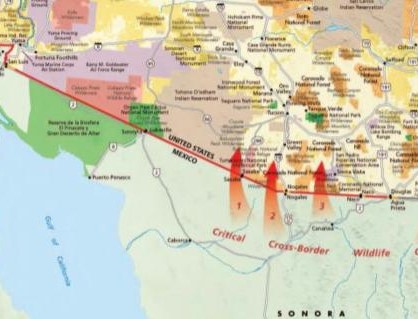

The call for more border security means border fencing that will likely cut across delicate desert plant and wildlife habitats. Located at the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands are vulnerable public and tribal lands and corriders by which wildlife migrate between nesting/breeding areas and foraging/hunting areas. The Cross-Border Wildlife map indicates critical wildlife migrating corridors where federal land, wildlife refuges, national forest, wilderness areas and tribal lands and lands for the Tohono O’odham Nation. The San Pedro Riparian Area is a unique ecosystem and rare in nature and home to 370 species of mamals, amphibians, reptiles and migrant birds. The vitality of these animal species are placed in danger when border fences are allowed to cut through these unique lands, without the associated effects being fully understood and properly mitigated (Doyle, 2014). The approach of this study is to learn what the presence of the border fence does on not just individuals, but the entire Arizona population and range of one species, the cactus ferruginous pygmy owl, (Glaucidium brasilianum cactorum), (heretofore as pygmy owl). This study will look at research done by field biologists on the pygmy owl’s habitat and behavior within its habitat. These studies were high priority ten to fifteen years ago due to the pygmy owl’s endangered status in 1997; they may give clues as to how the border fence effects the future of the pygmy owls population and range, thus the birds’ future in Arizona. My choice of the pygmy owl came from my curiosity that a bird could actually be hindered by a man-made wall and that this species was well studied due to its endangered listing by the federal government. |

|

|

Background The cactus ferruginous pygmy owls were listed as Endangered in 1997 and therefore the bird’s behavior, population and habitat studies were intensified by biologists in first half of 2000’s decade. In 2006, the owl was de-listed to Least Concern. Despite the change of status, the owl remains a focus for conservation to understand factors that affect habitat quality and the effects of human disturbance.(Flesch, 2007) The population and density of the pygmy owls in northern Sonora, Mexico was shown to decrease in range and numbers (Flesch, 2007). This has implications for the Arizona population that receives and could be depending upon those owls from Mexico which maintains/improves gene diversity for future viablity of the Arizona population. Factors affecting the success of cactus pygmy owl populations include nest success, clutch size, productivity and habitat size. Habitat linkages could provide connections for the movement of dispersing cactus ferruginous pygmy owls among local groups of pygmy owls on the Tohon O’odham Nation, in the Altar Valley, on Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, in northwest Tucson and in Pinal County. Without habitat linkages, the overall population of pygmy owls in Arizona is likely to become fragments to the extent that individuals may be unable to disperse and find mates and suitable blocks of nesting habitat. The United States’ border with Mexico, almost 2,000 miles long, is marked by about 670 miles of fencing and could play a large role in the interruption of habitat linkages. The majority of this fencing was authorized by the U.S. Secure Fence Act of 2006. This Act required the construction of double steel, 15-18 foot high walls along approximately one third of the U.S. border with Mexico, fencing in large portions of Arizona, California and Texas borders. This could be the biggest challenge yet to keeping Arizona's pygmy owls a viable population. | |

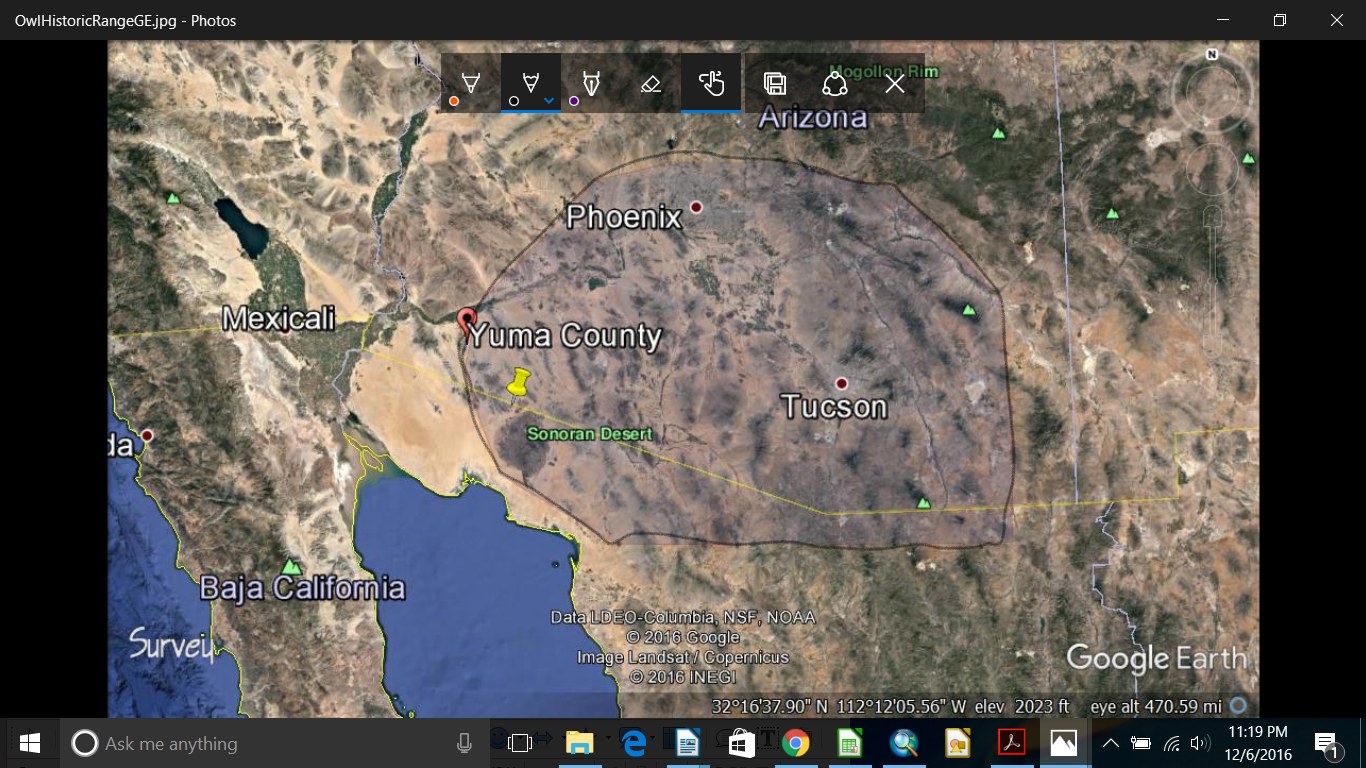

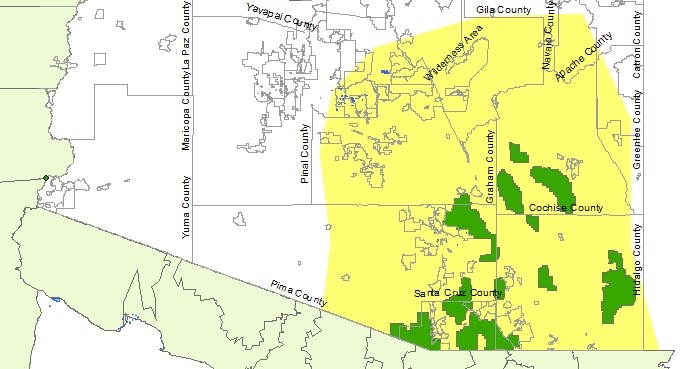

Methods I created a GIS map of Arizona, Sonora and the border crossing. Using Google Earth for one map and ArcMAP for another map, I plotted general boundary of the range in Arizona using the literature descriptions and the small scale generalized maps that showed the ranges in the small area of both Arizona and Texas which connects to Central America and South America (Brazil), hence the species name brazilianum. This helped me to see what part(s) of the Arizona border was in the owl’s range, historically and currently. |

|

|

To find a comparable study about how the border fencing can possibly effect animal behavior and, more importantly, the viability of their populations, I have taken Flesch’s research findings titled Roadways and Pygmy Owls in which he studied habitat quality and owl nesting near small and major roads to determine how these factors may, or may not influence the owl’s behavior and fledgling dispersal. Fledgling dispersal is a large consideration in population viability since this is the critical period of 70 days or less in which the young leave the nest and find their own territory. How far do they fly, what influences where they fly and where they eventually land and make their own territory are critical questions to answer to understand how the current fence and future fencing may change the areas of owl range. If the roads seem to deter the owl from settling or crossing an area, then the border fencing could have a similar or greater impact on owl behavior and range due to the fact the border fencing is taller than many trees in their habitat and not a likely perch for the owls, roads are located parallel to the fencing and a corridor is cleared of much of the native flora, leaving grasses only in a wide open area. To determine factors that explained the rate that pygmy-owls crossed roads, Flesch took into account the influence of home-range size, distance between nests and roads, traffic volume, road corridor width, and the relative probability of use of resources on the side of roads opposite nests. The study took place during the breeding seasons of 2003 and 2004, radio marking 19 territorial adult male pygmy-owls near roadways in northern Sonora. The study selected owls from nests located near four classes of roadways (small paved, large improved dirt, and small dirt, and high-use paved highways). | |

|

Results Results showed the population and ranges of the pygmy owl of Arizona decline during the field research between 2000 and 2006. The pygmy owls nesting behavior around roads demonstrated some tolerance, but as the human disturbance increased, the owls tended to show more avoidance behavior. | |

|

|

|

Historical boundaries of the owl range in Arizona, as described by Fisher 1893, Phillips et al. 1964, Monson and Phillips 1981, Hunter 1988) The historic range of the cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl was larger than today, ranging north to central and southern Arizona. The historical boundaries of its distribution in Arizona are New River in the north, the confluence of the Gila and San Francisco rivers to the east, and the desert of southern Yuma County to the west. |

|

Range of the pygmy owl in Arizona today has reduced in size since the last 60 years. Studies by Flesch of population trends of the pygmy-owl indicated a decline in populations near the Arizona border at Sasabe, Mexico between 2000-2006, before much of the construction of fence was underway at the border. Pygmy-owls in northern Sonora, Mexico declined by an estimated 4.4% per year or 26% over 7 years (Flesch, 2007). |

|

Figures and Graphs Arizona pygmy-owls are more difficult to study their movements and behavior near roadways due to their low numbers. Therefore the studies presented here are done in the pygmy owls' nesting habitat in Sonora, Mexico where they are more common and occupy similar vegetation communities as owls in Arizona. Thus this research has direct application for pygmy owl conservation in Arizona. | |

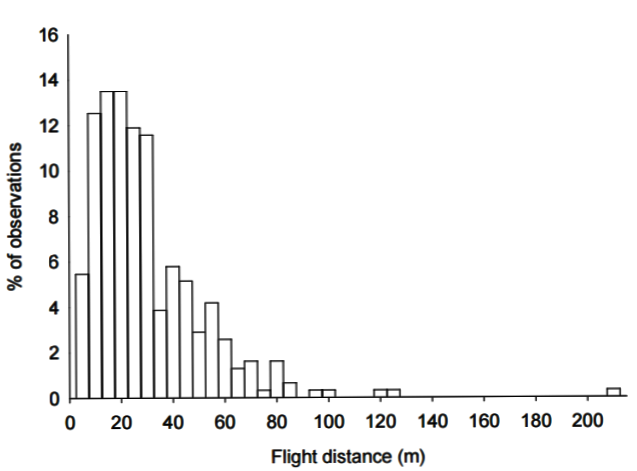

| Nineteen owls were tagged and observed in 2003 and 2004 in Sonora, Mexico. The results follow: 1. When the width of the road corridor increased, the number of pygmy owls road crossings decreased. 2. When traffic volume increased (determined by number and type of vehicles passing the nest area), the number of road crossings by pygmy owls decreased. 3. Flight distances were typically short, less than 40 meters. A few were observed to fly longer distances (>100m), which may have been more common than observed, due to the difficulty of technical issues of following these longer distances. Overall, 97% of flights were less than 80 meters in length. Flight Height: Flesch measured the average pygmy owls’ flight height to be 1.4 meters above ground and only 23% of juvenile pygmy-owls flew higher than 4 meters, (minimum height of the border fence). This indicates that most young owls (77%) would not make it over the border fence. The young owls flew at slower speeds, changed direction more, and had lower success colonizing in areas with larger vegetation openings or areas of high disturbance. (Flesch,2009) |

|

|

Analysis Many environmental factors described and studied by Flesch resulting in some avoidance behaviors are comparable factors the owls would most likely encounter at the border, such as, roads width, loss of vegetation, noise and lights. Add to these factors a four to six meter tall fence, the pygmy owls are at a great disadvantage.I had difficulty in finding spatial data for owl ranges and locations. To work around this, I created maps of Arizona and Mexico with spatial data that could impact wildlife, such as the border, border cities, roads, backgound topography, and government units. I found the data I found was dated in 200-2006. However, these studies were the basis for understanding owl behaviior and population trends. I also found current articles on the subject. I had difficulty finding spactial data for Arizona rivers. So I used Google Map to estimate the boundaries of Arizona's pygmy owl historical range which was described by location of rivers. With more time, I would have created Arizona maps that were comparable more clearly showing the difference of pygmy owl range past and present. My first challenge was finding little to no research data of the pygmy owls behavior around the border fencing. This project is a result of finding related data with which to draw conclusions regarding how pygmy owls may respond to the border corridors and the new fencing. | |

|

Conclusions The pygmy owl is shown to avoid areas of human disturbance and clearings. Their low flight limits their ability to cross a border with a 4 meter tall barrier. I conclude for the small pygmy owl population in Arizona, dependent upon owl’s from Mexico for genetic diversity, the border presents a sobering consequence for the Arizona pygmy owl’s range and viability in the future. Any additional or reinforced fencing along the Southwest border will continue to disrupt the migratory ranges of important endangered species. Recommendations: 1. Enhancing and maintaining landscape permeability should foster movement and immigration of pygmy-owls from Sonora to Arizona (Flesch, 2007) 2. Maintaining and restoring woodland vegetation along drainages and tall upland vegetation with saguaros will improve habitat quality for pygmy-owls (Flesch and Steidl 2006a). 4. Continued studies are important to determine and document the population densities and ranges of the pygmy-owl along the Arizona-border. Pygmy-owl decline in populations over relatively short periods may not indicate long term declines, and population monitoring programs must be continued (Robinson 1992). 5. To protect wildlife, barriers to information flow between science and policy will have to be made more permeable. (Phillips) | |

|

References Literature cited. Anon.2008. Effects of the International Boundary Pedestrian Fence in the Vicinity of Lukeville, Arizona, on Drainage Systems and Infastructure, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona, NAT’L PARK SERV. 1 (Aug. 2008), http://www.nps.gov/orpi/naturescience/upload/FloodReport_July2008_final.pdf. Flesch, A.D. 2006. Patterns and consequences of nest-site selection by ferruginous pygmy-owls and application to management using nest boxes. Presentation to USFWS Ecological Services Field Office, Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge, and Arizona Game and Fish Department, Sasabe, AZ. (only the abstract was available at no cost) Flesch, A.D. and R.J.Steidl. 2007.Association between roadways and cactus ferruginous pygmy-owls in northern Sonora Mexico. Report to Arizona Department of Transportation, A.G.Contract No.KR02-1957TRN, JPA 02-156. Flesch,A.D., Epps CW, CaiFleschn JW 3rd, Clark M, Krausman PR, Morgart JR. 2010. Potential Effects of the United States-Mexico Border Fence on Wildlife. Flesch, A.D.2007. Population and Demographic Trends of Ferruginous Pygmy-owls in Northern Sonora Mexico and Implications for Recovery in Arizona. School of Natural Resources. https://www.defenders.org/publications/ferruginous_pygmy-owl_demographic_trends_and_recovery.pdf USC. Public Law 109–367 109th Congress. Secure Fence Act of 2006, Pub. L. No. 109-367, 120 Stat. 2638 (2006). Van Devender, T.R. Avila-Villegas, S. and Emerson, M. 2013. Biodiversity in the Madrean Archipelago of Sonora, Mexico, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-67. . | |

|

Appendices The world on a map looks like the drawing of a cow In a butcher's shop, all those lines showing Where to cut. That drawing of the cow is also a jigsaw puzzle, Showing just as much how very well All the strange parts fit together. Which way we look at the drawing Makes all the difference. We seem to live in a world of maps: But in truth we live in a world made Not of paper and ink but of people. Those lines are our lives. Together, Let us turn the map until we see clearly: The border is what joins us, Not what separates us. | |