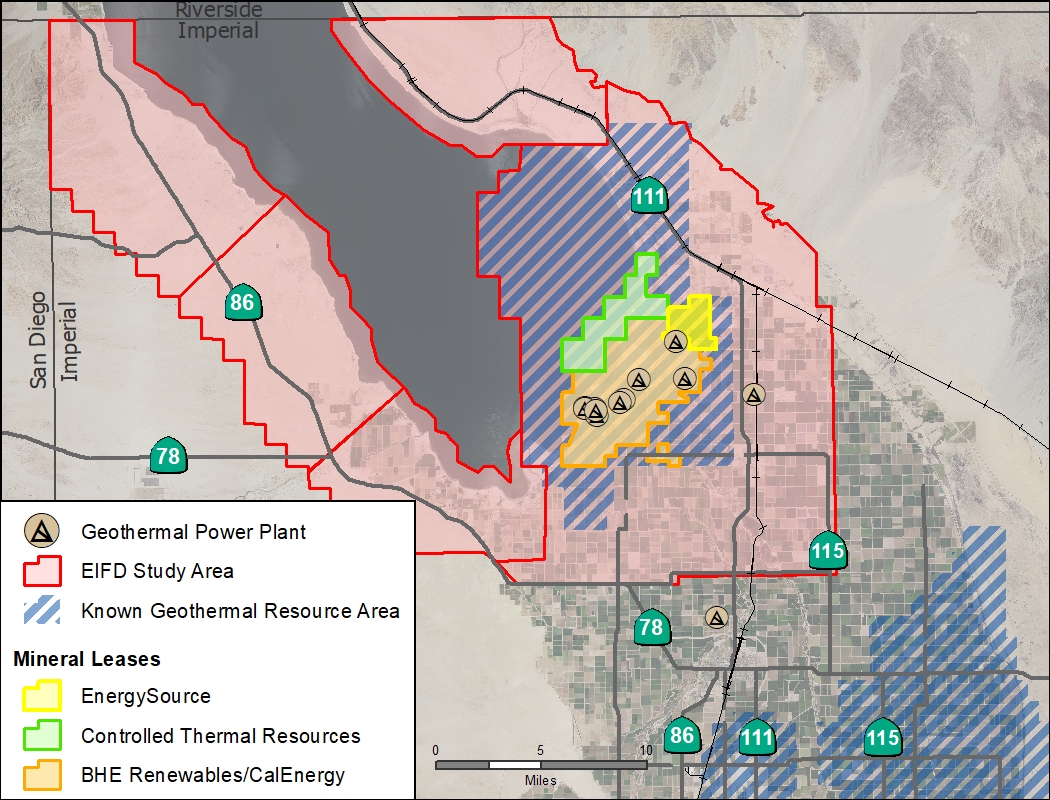

| Title Possible Sites for Lithium Mining in the Salton Sea Geothermal Area |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Author Barbara Lockhart

American River College, Geography 350: Data Acquisition in GIS; Fall 2019 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Abstract California law mandates 100 percent, carbon-free electricity by 2045.

Energy produced using solar or wind power can be stored in lithium-ion batteries, replacing some of the power

produced using fossil fuels. Lithium is a resource mined worldwide. As a means to further United States’ energy

independence, and specifically to enhance California’s role therein, the California Energy Commission announced

a $14 million fund specifically for the recovery of lithium from geothermal brine in October 2019. In support of

CEC staff work, maps were produced showing mineral lease holdings and infrastructure surrounding the Salton Sea

Known Geothermal Resource Area. These are possible sites for lithium mining.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Introduction Governor Jerry Brown signed California’s Senate Bill 100 (SB 100) into

law on September 10, 2018. This law mandates 100 percent, carbon-free electricity by 2045 (Koseff, 2018). The law

sets targets of 50 percent renewables by 2026 and 60 percent renewables by 2030. Some renewable energy sources such

as photovoltaic and wind do not generate electricity at a constant rate, so storage is necessary. Large lithium-ion

batteries are a cost-effective method of storage (Fu, Remo, and Margolis, 2018).Estimated lithium reserves in the Salton Sea Known Geothermal Resource Area (KGRA) of California could contribute substantially to the global demand for lithium products. Future lithium production have the potential to make the existing fleet of geothermal power plants more competitive in the energy market and additional associated revenues could benefit Imperial County. The Salton Sea KGRA is under consideration by several operators for lithium mining. Some considerations in the siting decision are transportation, environment, electric transmission capability, and land ownership. I will examine these factors spatially using a geographic information system to produce maps to help the decision makers. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Background

New lithium extraction technologies are under consideration. Elders,

Wilfred A., et al. (2019) propose accessing hotter and deeper resources than are currently accessed, specifically

at the Salton Sea Geothermal Field (SSGF). Their proposal is based on the success of two wells tested in the Iceland

Deep Drilling Project. There it was demonstrated that the possibility of drilling up to 4.5 kilometers deep produced

superheated steam upwards of 450°F. Power output increased for these wells in very high temperature supercritical

geothermal systems. These results are promising and may help California meet its energy goals. As of now, the SSGF

is underdeveloped because of competition from solar power.

The production of heat and lithium salts extracted from the same geothermal brine results in a potential economy of scope (Panzar and Willig, 1977). An existing geothermal power plant would likely be the most efficient approach to start lithium extraction in the Salton Sea KGRA. There would be advantages to permitting lithium extraction at an existing geothermal power plant in Imperial County, which currently hold permits for all of the existing geothermal power plants in the Salton Sea KGRA. The only additional permitting that may be necessary for lithium production is a conditional use permit from Imperial County based on industrial use. At a November 2018 California Energy Commission (CEC) workshop, one of the power plant operators – Berkshire Hathaway Energy (BHE) – indicated no new geothermal power development would occur in the Salton Sea KGRA without combined mineral extraction, and suggested that the revenue from lithium extraction could be as much as five times the revenue from power production (CEC, 2018a). The proceeds from lithium sales could also help offset a new power plant’s expected mitigation costs as well as support the Imperial County economy (Gagne et al., 2015). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Methods The CEC announced a $14 million fund specifically for the recovery of lithium from

geothermal brine in October 2019. Three private organizations currently hold mining leases at the Salton Sea’s southern edge.

One, EnergySource, is testing methods to extract lithium and “is making an expensive gamble that it can be the first to tap a

vast reserve of lithium here that has frustrated engineers for decades” (Ferris and Iaconangelo, 2019). CalEnergy/BHE and

Controlled Thermal Resources also own mineral rights.

Several meetings have been held on this topic, with pre-application workshops for potential applicants scheduled in late 2019 and early 2020. I was tasked to prepare maps for CEC staff in advance of the meetings, working under the direction of engineering geologist Dr. Garry Maurath. The maps were to show county, Salton Sea KGRA, and the Imperial County Enhanced Infrastructure Financing District (EIFD) boundaries, plus transportation, geothermal power plant, and mineral rights locations. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Results Table 1 lists the data sets and sources. Most of the data were available as

file geodatabases; however, the EIFD and mineral rights boundaries were digitized for this project. I digitized the EIFD boundary

using the "Draft EIFD Study Area Map" from the Imperial County Assessor's Office (McDaniel, 2018) and the mineral rights boundaries using BHE

Renewables’ figure "Salton Sea Geothermal and Mineral Resources" from the “Geothermal Grant and Loan Program Workshops and Discussions”

(CEC, 2018b), using standard georeferencing procedures. I stored all features, projected into the NAD 1983 California Teale Albers

coordinate system, as feature classes in a file geodatabase. Figure 1 shows the feature classes in map form. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table 1

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Figure 1

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Analysis In addition to the map described above, I created a series of maps for Dr. Maurath, some of

which included geological information such as faults and mineral resources. The maps proved to be useful to the team working on the

lithium initiative. I learned useful GIS techniques when doing this project. Prior to it, I had little experience georeferencing an

image. After struggling to manually determine spatial coordinates from the printed pdf files, a co-worker showed me how to turn the

pdf into an image (a raster for GIS), and create control points allowing me to properly georeference the features in the image. I spent

quite a bit more time performing the work for the project than I should have, but since it was a new technique to me, I feel confident

that I will perform better the next time I am presented with such a task.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Conclusions Much work is still to be done on the issue of lithium extraction from geothermal brine.

CEC staff will have more questions about lithium sources in the western United States, as well as worldwide. The product of this project

will continue to answer some basic geospatial questions of those that study the efficacy of lithium extraction in the Salton Sea KGRA.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

References

CEC, 2018a. Geothermal grant and loan program workshops and discussions. California Energy Commission Docket Log, Docket #17-GRDA-01,

https://efiling.energy.ca.gov/Lists/DocketLog.aspx?

docketnumber=17-GRDA-01Docket; web2019. 08.14

CEC, 2018b. Lead Commissioner Workshop on lithium recovery from geothermal brine. California Energy Commission Geothermal Grant and Loan Program Workshops https://www.energy.ca.gov/geothermal/grda_workshops/; web2019.11.12 Elders, W.A., et al., 2019. The future role of geothermal resources in reducing greenhouse gas emissions in California and beyond. Proceedings, 44th workshop on geothermal reservoir engineering, Stanford University, February 11-13. https://pangea.stanford.edu/ERE/pdf/IGAstandard/SGW/2019/Elders.pdf; web2019.09.25 Ferris, D. & D. Iaconangelo, 2019, October 30. How lithium could be Calif.'s next 'gold rush'. E&E News. https://www.eenews.net/; web2019.11.15 Fu, R., T. Remo & R. Margolis, 2018. 2018 U.S. Utility-scale photovoltaics-plus-energy storage system costs benchmark. National Renewable Energy Laboratory. NREL/TP-6A20-71714. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy19osti/71714.pdf; web2019.10.06 Gagne, D. et al., 2015. The potential for renewable energy development to benefit restoration of the salton sea: analysis of technical and market potential. National Renewable Energy Laboratory; https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy16osti/64969.pdf; web2019.11.12 Koseff, A., 2018, September 10. California approves goal for 100% carbon-free electricity by 2045. The Sacramento Bee. "https://www.sacbee.com/; web2019.10.06 McDaniel, C., 2018, July 26. Mapping out the possibilities: EIFD Salton Sea draft map submitted for review. Imperial Valley Press. https://www.ivpressonline.com/; web2019.08.14 Panzar, J.C. & R.D. Willig, 1977. Economies of scale in multi-output production. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 91 (3): 481–493. https://doi:10.2307/1885979; web2019.11.15 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||