| Title Creative Cities and Sustainability | |||||||||||

|

Author C. Marisol Ramirez American River College, Geography 350: Data Acquisition in GIS; Fall 2019 cmramirez713@gmail.com | |||||||||||

|

Abstract The following is a brief analysis of the impact of art and creativity on sustainable cities. The definition of sustainability is explored, referencing past ideas of community development along with newer ideological expansions on the topic. To provide a concrete analysis, a record of some of the art murals in the city of Sacramento was created and geocoded using ArcPRO software. You will see these murals mapped alongside census data and income data to better provide context. Multiple tools were used within the software in attempt to enhance a visual representation of said variables. | |||||||||||

|

Introduction What are the main thoughts evoked when imagining a flourished city? Economic vitality? A reliable transportation system perhaps? An engaged school system? What is it that makes the variables mentioned all that different to define a city as thriving? Some would argue community is the derivative of it all. It takes a solid community to keep local businesses booming, to sustain an accountable public transportation system, and to maintain student engagement and cohesive schools. Of course, other crucial variables exist that are vital to the well being of a city. Job availability, fair wages, ample funding, and diversity for example. But who will fight for these things, if not the community itself? It is important to go ahead and define what the word community means. It could mean a group of individuals who live amongst one another. Or it could mean more than that. A strong community shows a sense of social cohesion, engaging and thriving off one another. Involvement. Participation. It is only with an active community that culture forms and it is with cohesion and communication that community enhances the quality of life. There are multiple ways community involvement plays out in thriving cities today. From political activism, to neighborhood BBQs. Everything has an impact. Even art murals individuals pass by daily speak community to its members. To expand on this form of community involvement, an analysis of the murals of the city of Sacramento will be conducted in this project. The focus being the impact of community participation on the city itself. | |||||||||||

|

Background The main source used for this project is the organization called Sacramento Wide Open Walls. The organization focuses on promoting a sustainable arts scene throughout the city by advocating local, national, and international artists and encouraging citizens to participate in creative arts. Sacramento Wide Open Walls entices community members through their arts education programs, mural preservation projects and most notably through their yearly mural festival. The festival is ran by community volunteers and a board of directors. It is sponsored by multiple local organizations like Cap Radio, SN&R, SMUD, and KOLAS, to name a few. The Wide Open Walls mural festival was founded in 2016 and has continued to grow every year. | |||||||||||

While taking safety precautions due to the public health emergency in place due to COVID-19, the festival still took place in September of this year. The participation of international artists was cancelled but the festival was still held for a full eleven days. The murals portrayed by all local artists this year turned out to amplify diversity and harmony during a time of civil unrest. “I really think that getting those artists together, in times like now, is very important. It shows unity,” said artist Brandon Gastinell (qtd. in Labong). Sacramento Wide Open Walls keeps record of all the murals in the city of Sacramento, adding to their list since 2016. |

| ||||||||||

|

Review of Literature and Research Many have heard of community, regional, and urban development as practical courses of study. While relatively new explicit subjects, a conceptual understanding of how to maintain societies has always existed, even subtly. For decades, the concept of sustainability has been operationalized through economic and environmental variables, holding them as definitive measures for what entails a sustainable city. Both economic and environmental vitality are crucial to a functioning society, with economic forces, themselves, characterizing consumerism and capitalism. A strong argument showing a general lack of environmental interest throughout history, pointing out drastic climate change and limited resources has been made on numerous occasions (although maybe, still, not often enough). Even so it seems that most recently, sustainability has begun to dig even deeper into its ideological roots. To be sustainable, as defined by Merriam-Webster’s dictionary, means something is “of, relating to, or being a method of harvesting or using a resource so that the resource is not depleted or permanently damaged.” Sustainable is “of or relating to a lifestyle involving the use of sustainable methods.” With growing disparities between the rich and the poor (the have and the have nots), it seems as though resources are depleting. Or perhaps living in a market centered, competitive world creates an inequitable distribution of means. Is valuing profit over the health and existence of all humanity truly sustainable? And if yes, for whom? It is important to identify economic strength in a sustainable world and to identify where the definition comes from. Growing ideas of city and/or “community” development are beginning to question and acknowledge the role of the people, the working class, the proletariat. As noted by planning researchers Michael Carly and Harry Smith, “long-term strategic needs of the city for sustainable development and economic prosperity cannot be separated from the need to involve citizens at all levels of society in innovative ways of fashioning and participating in urban development processes” (4). Sustainable city planning requires involving residents in decision making. This is not to say there is no active citizen participation in current city planning but rather questioning to what extent and in what ways are people involved? “Prevailing discourses on urbanization in the developing world tend to neglect an understanding of the intricate processes by which people design their own places and spaces, how they sustain yet adapt local technologies and traditions, and how they deploy innate capacities to adapt cultural precepts to a modern idiom" (Watson, 4). Upholding creative, useful, and impactful public spaces has evolved to a practice that allows community to engage, express, and maintain their cities. Murals and art pieces continue to be and now more legally are, just one way citizens define their community as their own. | |||||||||||

|

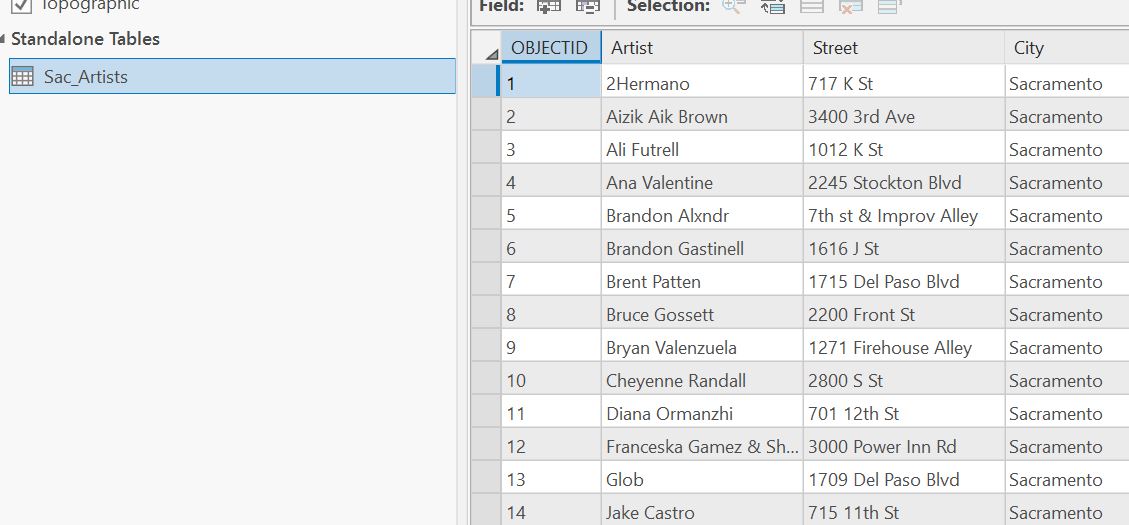

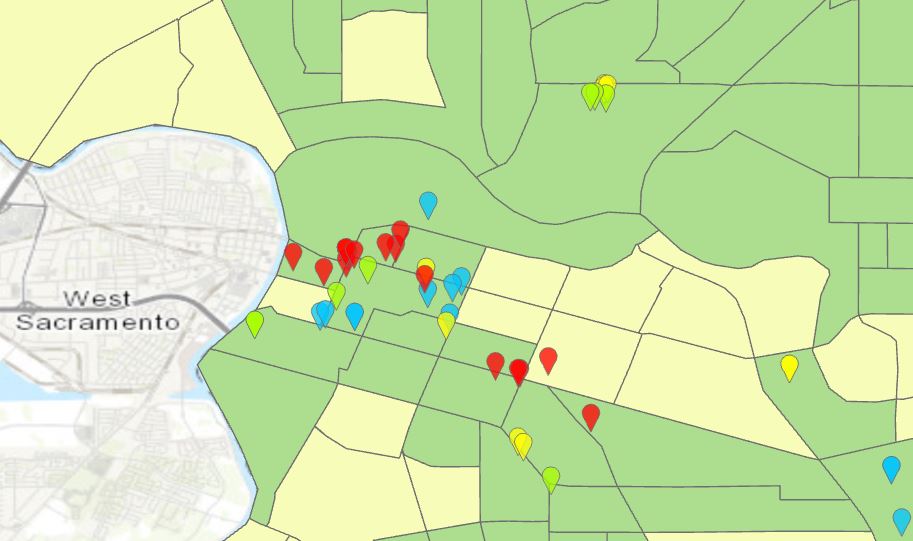

Methods Of all the artists listed on the Wide Open Walls website, only the pieces completed by local artists were the ones used for this analysis. This was to maintain focus on the power of community and local participation. First, a spreadsheet of all the local artists featured on the website was made, including the name of the artist, location of the artwork, artist website, artist focus, and year of production. This spreadsheet of 48 records was then imported into ArcPro and geocoded based on the addresses included. |

|

||||||||||

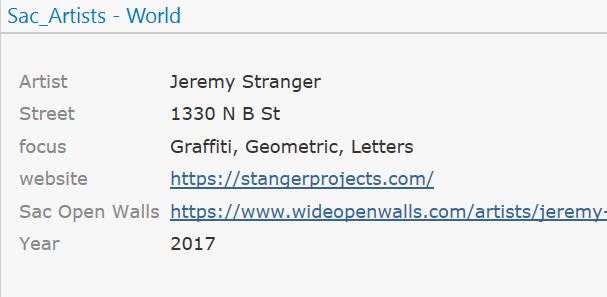

A modification of the symbolization was made to separate the point shapefile based on the year each mural was

created. This way a visual understanding of how many murals were added each year was made more apparent. Pop up boxes were also modified to show facts

about each point I.E. name of the artist, focus of the artist, website, Wide Open Walls artist’s page, location of their mural, and year.

|

| ||||||||||

|

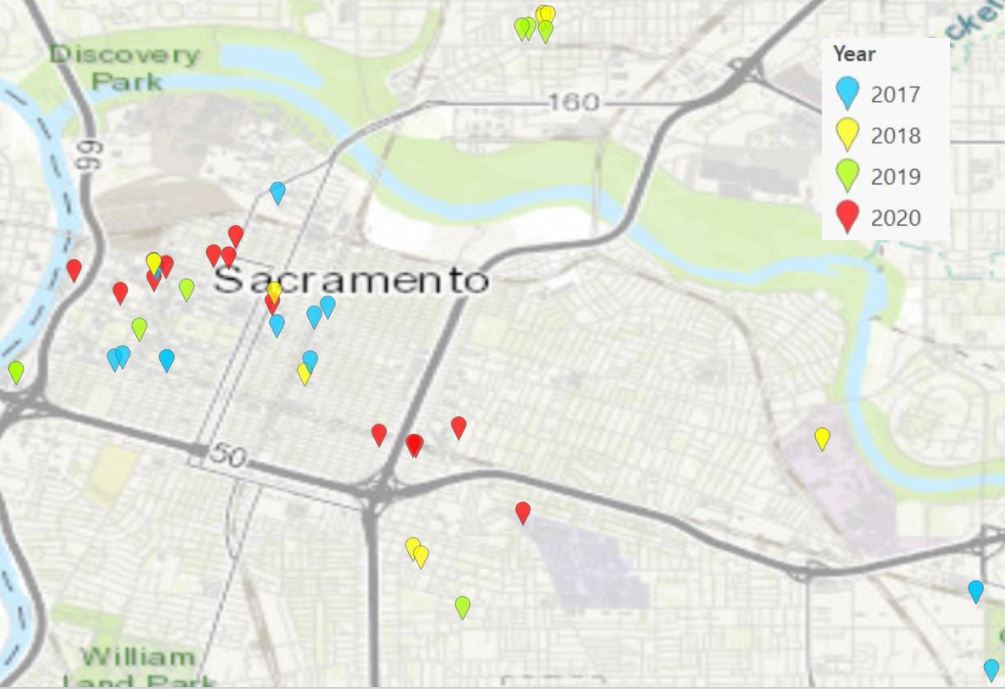

Methods Continued To make the map more interesting and to provide more than one variable, census data was added to the map. The census data allowed the symbolization of census tracts throughout the city of Sacramento. USDA data was accessible to download as well, giving more information about income and poverty within each tract. The census tract data was joined to the USDA data and the tracts were then symbolized based on median income. This is shown in the map below on the left. Upon completion, a second symbolization of the census tracts was made to symbolize which tracts are considered low income. According to the USDA a tract is considered low income if the “annual family income is at or below 200 percent of the Federal poverty threshold for family size.” This is shown in the map below on the right. The dark green tracts are considered low income, while the yellow tracts are not. | |||||||||||

|

|

The summarization tool was then used in multiple ways within this analysis. |

|||||||||

|

A summarization count was conducted for each year the mural festival has occurred. The table to the left shows how many murals were created during each year Sacramento Wide Open Walls hosted their main festival. | The table on the right is based off of the median income of all census tracts in the city of Sacramento. The median income of each tract is grouped into 5 classes of equal intervals. Using the summarization tool, along with the select by attributes tool, the number of murals was counted for each median income interval. |

|

||||||||

|

The summarization tool was used a third time to count the number of instances a mural was created in a low income census tract (as prior defined). The number 1 defines what is considered a low income tract, while the number zero signifies a non-low income tract. | ||||||||||

|

Results As shown in the tables above, the majority of the murals created since 2016 in the city of Sacramento are located in areas of lower income. 43 out of 48 murals are located in census tracts where the median income is below $45,183. Only 5 were created in areas where the median income is higher. We also see the same thing in the low income tract map. According to the summarization table, close to 98% of the art pieces are located in what is considered a low income tract. In fact, only 1 of the participating murals belongs to a non-low income census tract. Another interesting result is the number of murals created within each year. We see that the most murals were created this year, in the year 2020. Although resulting in just one more than the year 2017, 2020 took the lead. It is important to note that this analysis is assuming all entries have already been accounted for this year. | |||||||||||

|

Analysis It is indeed interesting that most murals for Sacramento Wide Open Walls are in lower income areas, but where there is a correlation there is no explicit causation. This analysis is based off only one organization’s record of art murals located throughout the city of Sacramento. The idea to focus on only local artists really speaks to defining community but also, might ignore the effect the remaining pieces have on the city and its people. It would have been best to document as much artwork throughout public spaces as possible, using multiple organizations perhaps. Even then, how should we measure the potential impacts of art and community involvement on the overall sustainability of a city? Since things like income and poverty have historically been used to signify success, those variables were considered in this project. There does seem to be a connection between public art and the areas where they are located, but the attempt to label this connection becomes somewhat diluted when focusing on sustainability. Mapping income and poverty levels against public murals gave this analysis more depth. Possibly better variables could have been incorporated though. The first example pertains to the median income of each tract. Mapping median incomes can be misleading since median calculations are greatly skewed when there are outliers in the data. Finding data representing the average income of the census tracts would conceivably demonstrate a more accurate portrayal of the areas. As mentioned prior, this analysis could have employed the focus more readily through the utilization of variables that directly pertain to art. Art, in our society, has an immediate association with consumerism. Ways to better measure that consumerism, besides poverty and income would be useful for a more realistic analysis. Centering on small details like symbolization of the point features and configuration of pop up windows, would be better suited for developing a user friendly application or completing a project whose purpose is to navigate the art works throughout the city. A general understanding of the murals in the city and the context to which they are found, has at the very least been initiated. | |||||||||||

|

Conclusions The concept of creative cities not only incorporates citizen input but prioritizes it. By engaging residents in designing and maintaining their own communities, an innate sense of responsibility and cherish can grow. If a city is only profit oriented, without any form of local participation other than consumerism, it is questionable whether those residents will consider themselves role players and decision makers. Giving the choice to design public spaces simply gives one additional way in which citizens can represent themselves and their input. If the community is not represented in its entirety, can the city strive towards true sustainability? This is not to say art and creativity will cease any groups of people from being marginalized but rather it is perhaps a steppingstone towards it. Creativity “does and can relate to communal identity, social belongingness, and a deeper sense of place as formulated by the broader demands of sustainability" (Ratiu, 1). Variables like those just mentioned can be ignored in a city only concerned with economic vitality. Expanding the definition of sustainability and bringing a focus on community and representation is progress. Upholding creativity seems to work well in engaging people and helping them be heard. Some ways the impact of creative cities can be concretely measured include long term studies of local businesses, observing their growth while the public space surrounding them changes. There would be other variables involved in determining the outcome of the business of course, but it would be interesting to see any patterns. A more feasible way would be to measure rates of tourism and tourism consumerism in cities with an inclination towards creative public spaces versus those without. As mentioned in a reading by Dan Ratiu, art and “creativity (are now being considered) as a “honey pot” to boost consumption and attract investment and visitors” (127). Thoughts of grand cities like Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco may come to mind. Cities with high tourism and submerged in street murals, unique public spaces, and attractions like museums and galleries. These aspects do not absolve cities of poverty and oppression but conceivably help empower people to participate and create change. Imaginably, only with an influx of community engagement, sustainability will be best defined. Gearing towards concepts like unity and equity will only encourage more creative ideas. Sacramento Wide Open Walls seems to recognize this with the work they do. | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

References Carley, Michael, and Harry Smith. Urban development and civil society: The role of communities in sustainable cities. Routledge, 2013. City of Sacramento Open Data, Census, 2010, data.cityofsacramento.org/. “Food Access Research Atlas.” USDA ERS - Food Access Research Atlas, USDA, www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/. Labong, Leilani Marie. “The City Archives.” Sactown Magazine, 6 Aug. 2020, www.sactownmag.com/category/the-city/. Ratiu, Dan Eugen. "Creative cities and/or sustainable cities: Discourses and practices." City, culture and society 4.3 (2013): 125-135. “Sustainable.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sustainable. Accessed 17 Nov. 2020. Watson, Georgia Butina. Designing sustainable cities in the developing world. Routledge, 2016. “Wide Open Walls.” WideOpenWalls, www.wideopenwalls.com/. | |||||||||||