Map 1.jpg

California’s New Zero Emissions Vehicles Rule: A Primer for the Average Citizen

Theresa Lechner

American River College, Geography 350: Data Acquisition in GIS; Spring 2022

Contact Information: W1949432@app.losrios.edu

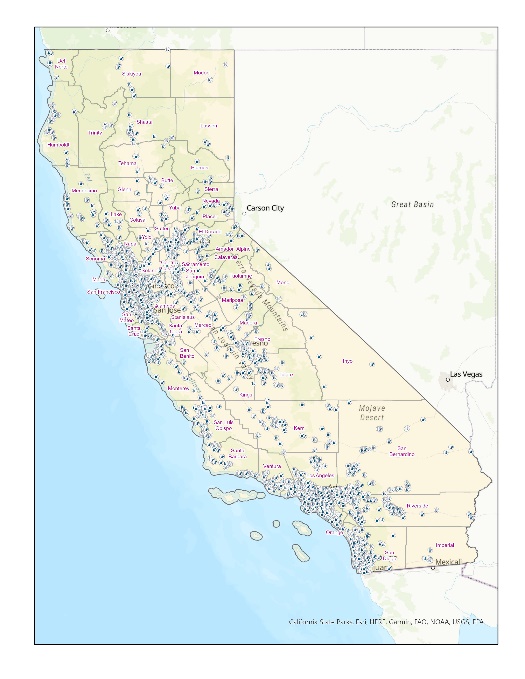

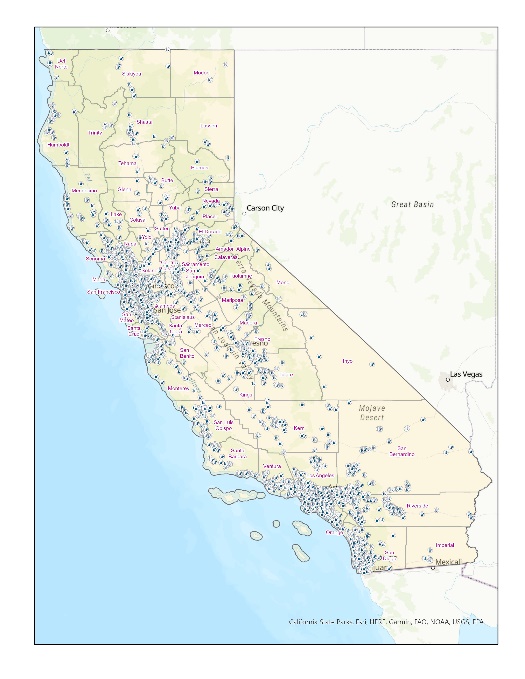

In August of 2022, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) approved the Advanced Clean Car II rule as part of the statewide initiative to make California a zero-emissions-vehicle (ZEV) state1. A primary goal of the rule is to require 100% of new cars and light trucks sold in California by 2035 be ZEVs and plug-in hybrids (PHEVs). While the number of ZEVs and PHEVs increased in the state over the years, many people, including the author, only have a general awareness of what ZEVs and PHEVs are, the charging infrastructure for these vehicles, and how widespread such infrastructure is in the state. This article gives a brief summary of the three topics along with several maps showing the location of public charging infrastructure illustrating how widespread such charging stations are in general but how some parts of California have a deficit that must be addressed if the 2035 goal is to be successfully met. It is concluded that while there are challenges presented by the new EV technology and there is a need to expand the charging network, California is well aware of the challenges posed by the new rule and is well positioned to make the necessary changes to meet its goals.

In August of 2022, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) approved the Advanced Clean Car II rule with a primary goal of requiring 100% of new cars and light trucks sold in California be ZEVs and PHEVs by 20351. In spite of a growing number of residents purchasing ZEVs and PHEVs over the years, many people only have a general awareness of what these vehicles are, the charging infrastructure, and how widespread the infrastructure is in the state. This article gives a brief summary of the three topics with an aim to make it as accessible as possible to the average person who wants information but is not interested in a highly technical discussion of the topics.

California’s involvement in air quality at the government level dates back to 1943 when the first recognized episode of smog occurred in the city of Los Angeles. In the early 1950s it was found that, while emissions from industry such as power plants and oil refineries contributed to air pollution, it was automobiles which were the primary culprits through exhaust emissions. In 1967 the state legislature passed, and Governor Reagan approved the Mulford-Carrell Air Resources Act that created the State Air Resources Board, thereby providing a statewide approach to air pollution control. Over the decades, CARB has spearheaded the adoption, implementation, and enforcement of pollution control regulations which has led to the Advance Clean Car II rule that was finalized in August of 2022, which puts California on the path of becoming a zero-emission vehicle state2. However, while the number of ZEVs and PHEVs sold has increased over the years, most people only have a general understanding of what zero-emissions-vehicles are and the infrastructure that is required for keeping the vehicles running both on a day-to-day basis and during long-distance travel for work or recreation.

The information for this project was derived from state and federal government websites. While the information regarding what types of vehicles fall under the ZEV and PHEV category, the levels of charging infrastructure, and funding for infrastructure can be found on various state and federal agency websites3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, finding information about location of charging infrastructure across the state that can be used by the public during long-distance travel was more difficult as none of the government open data sites at the state or federal level had a dataset with that information. However, I was able to locate a .kmz file with the location of public charging stations across the United States10. I took the .kmz data and, using ArcPro, converted it to a point file, set the coordinate system to Web Mercator (auxiliary sphere), and clipped it to the California boundary. The maps are derived from the converted and clipped data.Introduction section above. How were the author’s data selected, searched, collected, etc.

This project focuses on three topics; what are zero-emissions and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, the charging infrastructure for these vehicles, and how widespread the public charging infrastructure is in the state. The information acquired for each topic is summarized below. .

Electric vehicles (EVs) encompass all-electric vehicles (ZEVs), plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), hybrid vehicles, and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. However, the new rules focus primarily on promoting the manufacturing and sales of ZEVs and to a lesser extent PHEVs in the state. Traditional hybrids and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are not really addressed, so these two classes of vehicles aren’t addressed for project. Zero-emissions-vehicles are those that are powered exclusively by one or more electric motors, powered by batteries that are charged by plugging the vehicle into an electric power source. These vehicles produce no emissions from operation and have a driving range of between 100-400 miles depending on the model of car and type of battery, with an average range of 250 miles.

Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles are powered both by an electric motor and conventional combustion engine. These vehicles have an all-electric range between 15-50 miles depending on the model of car and type of battery. This range is generally sufficient for most daily uses and commutes by drivers, meaning the vehicle would be in electric mode most of the time, producing no emissions. The battery can be charged by plugging it into an electric power source. Once the battery is depleted the conventional engine takes over.

To comply with the new rules in California, ZEVs will be required to have a minimum range of 150 miles, include fast-charging capability, and come with a charging cord as standard equipment. These vehicles are also required to be full replacements to conventional vehicles, hold their value for owners, be quality used cars. They will also be required to have a 3 year or 50,000 miles powertrain warranty. As far as maintenance, ZEVs require much less than PHEVs. There are fewer moving parts in ZEVs to wear out, fewer fluids that must be maintained, break wear is less than in conventional vehicles and the battery, motor, and associated electronics generally require little to no maintenance. The battery is the largest expense of a ZEV and can cost between $2000 and $48000 depending on vehicle model and electric range. The average is about $20000. Safety standards for commercially available EVs must meet Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards and undergo the same testing as conventional vehicles.

To comply with the new rule in California, all PHEVs must have an electric range of at least 50 miles in real world driving conditions. In addition, the conventional engines in these vehicles are subject to new efficiency standards to help lower emissions while used in this mode.

For both, the rules require that, by 2030, all electric vehicles must maintain 80% of their electric range for 10 years or 100,000 miles and by 2031, individual battery packs must maintain 75% of their energy for 8 years or 100,000 miles.

Charging EVs requires an infrastructure that can be easily accessed by those who own EVs. There are three levels of charging infrastructure for EVs:

Level 1 charging is for residential use as it is done simply by plugging your vehicle into a household (120-volt) outlet. Except for a charging cord, no additional infrastructure is required or needed. This is the slowest, but most convenient, method of the three and will yield about 40 miles of driving range per 8 hours of charge. It works best for PHEVs since they have a small battery and range. It can take several days to fully charge a ZEV battery if the level gets low. The cost of Level 1 charging depends on range of the electric battery, the time of day you charge, and how much you pay for your electricity. On average, a battery with a 150-mile range will cost about $7.00 to fully charge.

Level 2 charging infrastructure is both residential and public in nature. This level is faster than the previous one as it uses a 240-volt circuit (similar to the one used by household clothes dryers), and it can yield between 14-35 miles per hour of charge. However, as it requires a dedicated circuit and specific equipment, it could be costly to have one installed at a residence. The Level 2 charging station is the most common for public use and can usually be found at shopping centers, grocery stores, and major travel corridors. There are rebates available though state and local governments to help defray the cost of the infrastructure, but it can still cost several thousands of dollars to install the equipment. The cost of using the Level 2 charging depends how long you use it and how the owner has set it up. It can be free (rare), pay-as-you-go, or subscription-based, with the amount charged set by the owner of the station. These stations generally require the user to have an app on their phone connected to some form of payment to use. Some do have credit card readers, but these seem to be rare. Regardless, it seems to be widely agreed that the cost of charging a 150-mile battery will be more costly by several dollars than a Level 1 station.

Finally, the DC Fast Charging stations are the fastest way to recharge a vehicle with a rate of about 100 miles in 30 minutes. However, they are only available for public charging, and they are not as widely distributed as the Level 2 charging infrastructure, although they can be found in shopping centers, grocery stores, and major travel corridors as well. As with Level 2 stations, payment type and amount charged is determined by the owners of the charging station. These stations also generally require the user to have a phone app in order to use the charging station. This is the costliest form of charging with estimates of $16 and above for a 100-mile charge. However, when traveling long distances it is the fastest and most efficient way to keep moving.

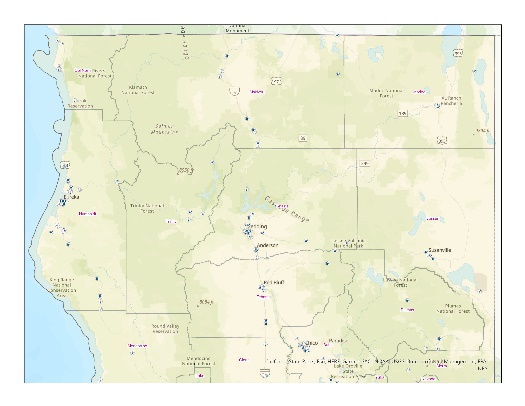

Finally, I looked into the location of public charging stations to get an idea of how easy long-distance travel within the state would be. I discovered that prior to the new rule, California had been expanding public access to charging stations across the state as part of the West Coast Electric Highway initiative which also includes British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon. The goal was to provide a network of fast charging stations every 25-50 miles along Interstate 5, Highway 99, and other major travel routes, giving individual drivers confidence they can drive longer distances for travel or recreation and encourages more individuals and businesses to invest in EVs. As a result of this initiative, the west coast now has a very robust charging network with hundreds of DC fast chargers and thousands of Level 2 chargers along highly traveled corridors. However, this does not solve the issue of few charging stations in more remote or rural areas in the state. To fill this gap, California submitted the California Deployment Plan for the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) Program to the United States Joint Office of Energy and United States Department of Transportation for approval, which was granted in September of 2022. This approval makes $56 million immediately available for upgrading existing charging infrastructure, charging station operations and maintenance, the installation of new charging stations across the state. An additional $384 million will be granted to the state over the next four years under the program. The goal is to complete a 6,600-mile statewide charging network consisting of 1.2 million chargers by 2030 to meet anticipated need due to the shift to ZEVs and PHEVs, with particular focus on more rural areas and long-distance corridors.

Map 1 shows locations of public charging stations throughout California. Map 2 shows a close-up of Northern California and the sparse distribution of public charging stations

Map 1.jpg

Map 2.jpg

While California has made great strides in emissions reduction through policy mandates regarding ZEVs and PHEVs and funding of charging infrastructure across the state, development in vehicle technology and continuing construction of charging stations must continue if the ultimate goal is to eventually eliminate conventional vehicles in the state. Currently, the overall cost of an EV is more than a conventional vehicle and progress must be made in the direction of cost parity between EVs and conventional vehicles. Further, more progress must be made on the batteries that power EVs, by extending the life and driving range as well as finding ways to lower replacement costs. As it is now, replacing the battery is the largest expense in owning an EV, with an average replacement cost of $20000. Regarding public charging stations, the overall map of California clearly shows an extensive network of public charging stations currently exists, but it is also obvious that there are areas in the state with little to no coverage and that must be addressed if drivers are to be free of ‘range anxiety’ in these areas.

California has mandated that by 2035 (12 years) that 100% of the cars and light vehicles sold in California be ZEVs or PHEVs. This influx of EVs requires that an extensive network of public charging stations be up and running across the state to meet the needs of the new technology and to give drivers confidence that they can continue on with the long-distance travel for work or recreation that they are used to with conventional vehicles. I believe that the information presented shows that California is aware of the challenges presented by the new EV technology and the need to expand the charging network and is well positioned to make the necessary changes to meet its goals.

1 California Moves to Accelerate to 100% New Zero-Emission Vehicle Sales by 2035. California Air Resources Board Press Release 22-30. August 25, 2022. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/news/california-moves-to-accelerate-100-new-zero-emission-vehicle-sales-2035. Accessed September 27, 2022. Geographical & Environmental Modeling, 1(1):5-23.

2 History. California Air Resources Board. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/about/history. Accessed December 4, 2022. Geographical & Environmental Modeling, 1(1):5-23.

3 Electric Vehicle Basics. U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. https://afdc.energy.gov/files/u/publication/electric-vehicles.pdf. Accessed November 28, 2022. Geographical & Environmental Modeling, 1(1):5-23.

4 Electric Car Overview. California Air Resources Board. https://driveclean.ca.gov/electric-car-overview. Accessed November 28, 2022. Geographical & Environmental Modeling, 1(1):5-23.

5 Battery-Electric Cars. California Air Resource Board. https://driveclean.ca.gov/battery-electric. Accessed November 28, 2022. Geographical & Environmental Modeling, 1(1):5-23.

6 Plug-in Hybrid Electric Cars. California Air Resources Board. https://driveclean.ca.gov/plug-in-hybrid. Accessed November 28, 2022. Geographical & Environmental Modeling, 1(1):5-23.

7 Maintenance and Safety of Electric Vehicles. U.S. Department of Energy, Alternative Fuels Data Center. https://afdc.enenrgy.gov/vehicles/electric-maintenance.html. Accessed December 4, 2022. Geographical & Environmental Modeling, 1(1):5-23.

8 Electric Vehicle Charging Overview. California Air Resource Board, Center for Sustainable Energy. https://driveclean.ca.gov/electric-car-charging. Accessed December 6, 2022. Geographical & Environmental Modeling, 1(1):5-23.

9 Electric Car Charging Overview. California Air Resources Board. https://driveclean.ca.gov/electric-car-charging. Accessed December 6, 2022. Geographical & Environmental Modeling, 1(1):5-23.

10 Alternative Fueling Stations Data. U.S. Department of Energy, Alternative Fuels Data Center. https://afdc.energy.gov/data_download. Accessed December 6, 2022. Geographical & Environmental Modeling, 1(1):5-23.

11 Federal Funding to Help California Expand Electric Vehicle Charging Network. California Energy Commission. https://www.energy/ca.gov/news/2022-09/federal-funding-help-california-expand-electric-vehicle-charging-network. Accessed December 6, 2022. 12 West Coast Electric Highway. Washington State Department of Transportation. https://www.westcoastgreenhighway.com/electrichighway.htm. Accessed December 6, 2022.Geographical & Environmental Modeling, 1(1):5-23.

12 West Coast Electric Highway. Washington State Department of Transportation. https://www.westcoastgreenhighway.com/electrichighway.htm. Accessed December 6, 2022.