Background

Abstract/Introduction | Methods | Results / Analysis | Conclusion | References

LocationAchillbeg is a small island off the southern shores of Achill Island, Co. Mayo, Ireland. It is approximately 256 acres in area and 2.25 km in its longest dimension. Achill Island is the largest and most westerly of the Irish islands.

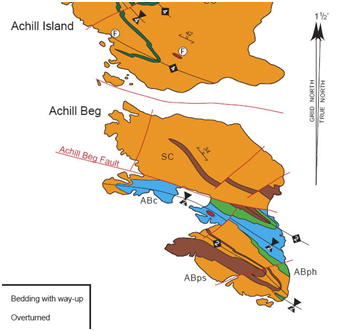

GeologyThe island itself has a facinating geologic history with a fault line separating the northern and southern portions of the island.

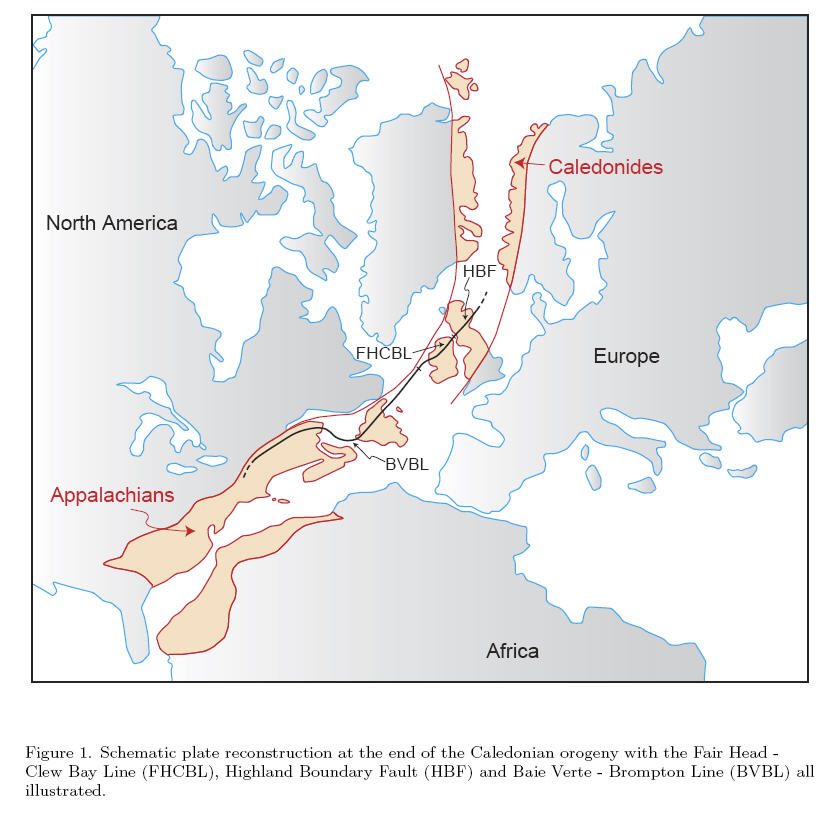

The geology represented in the rocks on either side of the Achillbeg fault may represent a time period going back 500 MY ago during the Ordovician and prior to the major development of the Atlantic Ocean. Rocks here share origin characteristics with those in Scandinavia and the Northern American Appalachian Ranges on either side of their respective major fault lines (Chew, 2005 ).

These differences in geology had

been noted by the islanders and by tradition the northern hill has

been ‘part of Mayo’ and the southern hill ‘part of Connemara’ PrehistoryMost of Ireland was covered by glaciers until the

retreat of the last (Midlandian) phase 10-12,000 years ago. There is conflicting evidence

regarding the exact extent over Achill Island, but there are corrie

lakes and also relict flora of Arctic-Alpine, Lusitanian and North

American species as unique findings on the island No exact dates can be given due to lack of definitive

archaeological evidence, but it is likely that Achillbeg was

inhabited by Mesolithic hunters/fishers/gatherers sometime in the

last 5-7,000 years ago. By 2-4000 years ago it was most certainly

inhabited and the great promontory fort Dún Chill Mhór (Dún Kilmore)

is likely from that era Neolithic practices arrived about 5,000 years ago and

left not only the megalithic tombs that help mark that age, but

generated changes that had the most marked effect upon the

landscape. Prior to the introductions of grazing animals and cereal

cultivation, the landscape was heavily wooded. As these agricultural

activities progressed, the plant communities and soils were altered.

This is a cool temperate, but wet and very windy environment. As

cultivation increased and woodland cover decreased, there was

gradual increase in heathers and other moorland plants. The soils

became more leached and acidic which accelerated the whole process.

Gradually blanket bog plant communities spread from the hills to

include more and more arable land. As the bogs matured, the peat

forming there gradually buried both the natural and manmade features

of the island Historic PeriodThe Early Christian / Early Medieval Periods date from the 5th century CE with the coming of St. Patrick. An early recorded name for the Island was Kil-da-mat or Kildavnet (possibly named after a saint Davnet of the 7th century). These is also an old stone cross within the Dún Chill Mhór promontory fort and folk tradition relates that a wooden church was sited there from the 6-1oth century. Co. Mayo has historically been one of the poorer regions in Ireland and due to poor growing conditions over much of the area. During the time of the Great Famine (An Gorta Mór) in the 1840-50’s there was a great depopulation due both to starvation and emigration. The recorded population of Achillbeg dropped from 178 in 1841 to 93 in 1871. The 2oth century saw a continuing decline in population – during the first half of the century there was a continuing pattern of seasonal migration of the able-bodied (men and women down to early teen years) to other parts of Ireland, Scotland, or other parts of Britain for work in the potato fields. Despite its remoteness, Achillbeg even had incidents related to War of Independence and the Civil War that followed in the 1920’s with the IRA hiding a cache of rifles under a rock by the main road. There was little government interest in the island through the remaining years and the islanders were becoming increasing remote. During the 1930’s some of the older dwelling (one or two-room stone huts with thatched roofs) were replaced by newer structures and by the 1950’s most homes had replaced open fires in the kitchens with gas or solid fuel stoves – but still no electricity nor phone. A lighthouse was constructed between 1963-5 – it was the need for electricity to power this that finally led to power being brought to the island. Unfortunately storms wrecked both the poles and underwater cables and power was not restored until later in 1965 after the population was gone. It was during this time that the decisions were made to evacuate the dwindling and aging population of the island. By end of October, 1965, the remaining 26 residents had left – mostly relocating to Achill Island. Being a confirmed monolinguist,

the issues of interpretation and pronunciation of Irish were

somewhat problematical. Luckily Achillbeg, by Jonathan

Beaumont The content of his Chapter Twelve (Place Names) is summarized below: There is a long and rich tradition of localized place names in all of Ireland and Achillbeg is not an exception. Names can have their origins in geographic or geologic features, relate to agricultural activities, or serve to commemorate persons or events either famous or infamous. These names may or may not appear on official maps, but are a part of the local memory and most often are only included in oral tradition. Irish spellings will vary – ‘Tra bo Dearg’, ‘Traboderig’ or in correct Irish, ‘Trá Bó Deirge’ is best translated as the ‘beach of the red cow’. ‘Tra’ or ‘Traw’ are both Irish for ‘strand’. Beaumont suggests an English pronunciation of ‘TRAW-bo-Jarrig’ (EMPHASIS on CAP syllable). I have followed his suggestions for the creation of this database. More examples: The southern hill was recorded as ‘Knockillanaskra’ on an 1855 map and could likely be pronounced ‘KNOCK-ILL-AN-ASKRA’ by an English speaking surveyor, but none of the residents of Achillbeg had ever heard of such a place. The Irish name is ‘Oileán an Sciorta’ the ‘island of the ticks’. The pronunciation is ‘Lawn-is-gurta’ and may represent a loss/dropping of the initial ‘Knockill…’ to the shortened version with ‘gurta’ being a closer pronunciation of ‘askra’ in the local Irish dialect. The following photo of mine matches a description given by Beaumont and is an example of the richness of this naming tradition.

‘…here we are looking

across at Aill Taghnach (Taghnach’s cliff) from Uaich na Sionnach,

the ‘cove of the foxes’. For a start, there are three coves – Uaich

na Sionnach Mhór, (the big fox’s cove), Ualch na Sionnach Láir (the

middle, or central, foxes cove), and Uaich na Sionnach Beag (the

small fox’s cove)…The hill is Oieán an Sciorta, the ‘land of the

ticks’, and the area in front is Athoire, the meaning of which is

uncertain. Along the top of the cliff is Cosán na nGabhar, the

‘goat’s path’. The small grassy outcrop in front is Gob an Bhioráin.

This probably means ‘the end of the point’ though ‘Bioráin’ means a

stack or pinnacle of rock (in the sea)…The narrow strip connecting

Gob an Bhioráin with the rest of the island is An tSiorán, the

‘pinnacle of rock’. The area to the left of the picture just above

the small stony beach is Athoire, which possibly means a ford across

tidal rocks.’ The 'Standing Stones' have an excellent web

page for Irish Pronunciation: http://www.standingstones.com/gaelpron.html

|

|

(

(